PDF Version[1]

2025 Stuart L. Bernath Prize Winner[2]

Department of History, UC Santa Barbara

In her last will and testament, created within a year of her death in 1568/9, Isabel Steyver of Locking in Somerset, England, disposed of all her earthly belongings in roughly two paragraphs. Isabel bequeathed first to her parish church, then to the village poor, then to her daughter, Flower:

I give unto Flower Styver my daughter [sixty-six] poundes [thirteen shillings] [four pence] with her fathers legacye to be paide to her at the daye of her maryadge and yf the abovenamed Flower doe happen to dye before she be maryed, that then my will is the abovenamed lagacye shall remaine unto John Steyver my sonne saveinge [six pounds] [thirteen shilling] [four pence] which is my will that Julyan Sprude my daughter shall have.[3]

Isabel goes on to name a few more bequests to her godchildren and son-in-law before leaving the bulk of her estate and cattle to her son, John, naming him as the executor of her will.[4] The significance of Isabel’s will lies beyond its adherence to traditional early modern inheritance practices favoring male heirs; instead, Isabel’s will can be interpreted as focusing on her female heirs as the beneficiaries of specific personal bequests, addressing Flower’s future need for a dowry and Julyan’s persisting need for financial autonomy as an already-married woman.

As general charitable bequeathing to the Church trended downward in the context of the English Reformation, wills became more prominent tools for distributing a testator’s earthly possessions to benefit people in their lives rather than save the testators’ souls in the eyes of the Church. The frequency and makeup of specific bequests by elite testators to certain kinship demographics in their wills suggests that wills provided a unique means of empowering less advantaged societal demographics within their communities and that women leveraged this opportunity differently than men. Analysis of wills created by elite men and women, proved by the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in England between 1558 and 1569, provides insight into informal support networks illuminated by the gendered similarities and differences in bequeathing practices.

English Will-Making and Inheritance Over Time

The term “last will and testament” comes from a blurred medieval distinction between the testamentary disposal of moveable personal property and the “last will,” a separate document concerning real property–meaning land or affixed to land.[5] The Church of England gained jurisdiction over the probate of testaments (not real property) during the Middle Ages, concerned with preparing Christian persons for death to help their souls in the afterlife.[6] Statutes of certain English dioceses aimed to require a priest to be present at all testaments to observe commitments of the soul to God, pious bequests, and earthly reconciliations that were often involved.[7] Literate clergy and a growing mercantile population assisted in the increase of written wills during this period.[8] As such, the Church of England influenced the development of will-making practices as early as their rise to popularity in the Middle Ages, remaining a potent factor through the early modern period.

English common law inheritance practices for real property in the medieval period followed male-preference primogeniture and coverture doctrines, usually yielding the entire estate to the eldest son to pass to his male heirs.[9] If the deceased had no children, estates passed to the closest male relation of the father.[10] Common law allowed women to inherit from a parent only if they had no brothers; in this case, the oldest daughter would inherit jointly with any younger sisters.[11] The doctrine of coverture held that the legal identity of a married woman would be “eclipsed” by that of her husband, making her unable to sign contracts, sue, or obtain credit.[12] Similarly, married women could only make a will with the expressed consent of their husbands.[13] In this way, the feudal system influenced medieval inheritance practices by focusing on the eldest male heir to “prevent the fragmentation of landholdings and maintain the economic stability of noble families.”[14] English aristocrats utilized primogeniture and coverture doctrines to keep estates from transferring to the married names of female beneficiaries, ensuring the survival of patronymic legacies.

Another prominent feature of inheritance beginning in medieval England was the origin of English uses, or trusts, which allowed landowners to transfer legal ownership of their property to trustees, who could oversee the property for the benefit of designated beneficiaries.[15] Uses allowed landowners to bypass feudal inheritance traditions and flexibly manage estates, although the law courts did not recognize them.[16] It is thought that the practice originated in the fourteenth century from ecclesiastical legal scholarship to avoid prohibitions against religious organizations owning land.[17] In 1535, Henry VIII enacted the Statute of Uses to “restore the sources of revenue lost by avoidance of feudal obligations and to prevent further confusion resulting from secret uses.”[18] The Statute of Uses essentially eliminated the practice and significantly limited the Church’s ability to accumulate landholdings during Henry VIII’s dissolution of monasteries.[19] Uses are relevant to this study because historians have linked the Crown’s sale of monasterial land to the wealth of several testators in this sample.[20]

The onset of the English Reformation, marked by King Henry VIII’s departure from the Catholic Church in 1534, catalyzed substantial changes in English will-making practices, most evidently the stark decreases in priests’ involvement and charitable bequests to religious institutions. Clerical participation in the creation of an early modern will is evidenced by priests named as witnesses, sometimes heading the list in an indication that the priest may have authored the will.[21] In a case study of approximately eighty Norwich consistory court cases made between 1520 and 1547, more than fifty percent of the wills were clearly penned by priests.[22] Under Edward VI, the Norwich consistory court books suggest that around one-third of wills were written by priests, falling to little more than one-sixth by the second year of the reign of Elizabeth I.[23]

The Edwardian Reformation led to the removal of many traditional priestly responsibilities. It made religious sacraments less widely available by removing many stipendiary appointments and relegating clergy to unbeneficed pastoral positions.[24] Under Mary I, it is true that the restoration of Catholicism influenced the prevalence of the last rites and priestly incorporation; however, high mortality in the 1550s left a shortage of will-writers, resulting in an even lower proportion of wills with priestly involvement.[25] The English Reformation’s influence on broader English social aspirations influenced will-making trends in charitable bequests, with “safety of the soul being less likely to be achieved by generosity.” Therefore, the poor and other secular beneficiaries surpassed the Church as recipients.[26]

Until 12 January 1858, the Church of England and other courts of hierarchical jurisdiction and authority oversaw the proving of wills of deceased persons in England.[27] The lowest courts were peculiar, manor, and other special courts with jurisdiction over a parish or small locality.[28] In the early modern period, manor courts had jurisdiction over disputes regarding freehold or copyhold land and settled them using common law tradition.[29] Peculiar courts were ecclesiastical courts that lay outside of the bishop and archdeacon’s jurisdiction, operating outside of the typical diocesan structure.[30] If a person owned property within the jurisdiction of two or more lower courts, their account would ascend to a higher court such as the Archdeaconry courts.[31] Above the Archdeaconry courts, the Bishop’s courts (also known as Episcopal, Commissary, Diocesan, or Consistory) served as the highest court within a diocese.[32] The Prerogative Court of Canterbury and the Prerogative Court of York were the highest probate courts affiliated with the Church of England and primarily had jurisdiction over wills containing property in more than one diocese or wills of testators with property or residence outside of England.[33]

Literature Review

In the study and interpretation of early modern probate documents, there is some debate about the utility and implications of wills as sources. Historians have been criticized for failing to evaluate the nature of wills beyond a superficial understanding of the character and function of the documents themselves.[34] The nature of this argument relates to historians’ fragmented focus on specific aspects or collections of wills independently of the context of laws and traditions pertaining to proprietary succession, “pressing wills into historical service” for a limited understanding of their utility.[35] English probate did not operate in isolation from changing social structures and ideas; subsequently, end-of-life transmission came under the purview of overlapping institutions governed by canon law, common law, equity, and custom.[36] Additionally, several “competing jurisdictions” of interest, such as that of the landlord or state, curtailed the intents of testators and the desires of beneficiaries.[37] Moreover, will-making in the early modern period followed specific frameworks and utilized boilerplate outlines. One 1529 act instructed testators to meet four major requirements in their wills: the payment of debts, the “necessary and convenient [funding] of their wives,” the respectable upbringing of children, and the “advancement of children to marriage.”[38] Additionally, in line with social customs of the time, the act advocated for testators to perform charitable deeds.[39] Some aspects of wills have been previously wrongly identified as reliable indicators of a testator’s inclinations. For example, historians have realized that religious preambles in wills are not conventionally useful as indicators of a testator’s faith due to the cultural ritual of will-making formulae in the period, which generally included a religious invocation.[40] However, departures from the typical testamentary invocation in this sample in terms of length and complexity can demonstrate different levels of piety or religious affiliations, raising some interest in the significance of a testator’s license in creating their will. Some historians conclude that wills were not produced for posterity, but rather that wills are documents of record made for the court of law.[41] This research opts to utilize wills as “evidence of personal relationships, religious beliefs, and social aspirations” by considering the nature of wills as documents, the license available to testators through will-making, as well as the overlapping social contexts surrounding will-making in early modern England.[42]

Considering gender in the research of early modern will-making, Women and Property: In Early Modern England by Amy Louise Erickson serves as a foundational analysis regarding women’s proprietary practices and will-making data in early modern England. Erickson focuses on patterns of property ownership and transfer among ordinary men and women between 1580 and 1720 as part of a larger historiographical trend expanding beyond the focus on the elite. Erickson utilizes a broad scope of probate documents–namely probate accounts–and documentation of lawsuits over marriage settlements, including women of different periods, localities, and relationship statuses (i.e., married, widowed, single, remarried) to extrapolate trends and abnormalities regarding the lived experience of property ownership. Erickson posits that impersonal legal documents are the “only” reliable vantage point for observation of early modern women’s lives; consequently, Erickson supplements information gathered from probate documents with sparsely available autobiographical accounts and contemporary writings.[43] Erickson points out that many early modern women who produced supplementary written materials were “well-to-do and not overburdened with domestic cares or children,” creating a distinction in the breadth of analysis possible between elite and ordinary women.[44]

Erickson’s research concludes that the average woman’s experience of proprietary ownership in the early modern period diverged considerably from the theoretical frameworks behind it. Despite traditional ideas about the benefits of primogeniture and coverture to the aristocratic male hierarchy, Erickson’s research finds that daughters inherited from their parents on a very comparable basis to their brothers in terms of value; still, women did inherit more personal property, while male heirs more often received real property.[45] Moreover, wives retained substantial separate property interests and made property settlements in every class demographic.[46] Erickson notes that “widows commonly enjoyed much more property from the marital estate than the law entitled them to,” and commonly gave preference to female relatives in the disposal of their property, perhaps in “tacit recognition” of women’s inaccessibility to financial independence.[47] Widows made wills perhaps more frequently than any other demographic, and their beneficiaries feature a wider array of kin than the average will of a male testator.[48] On the ordinary level, widows made up the majority of those in poverty, as the majority of lower-class men died intestate and without provisions for their surviving spouse.[49] Ecclesiastical courts adapted the practice of intestate distribution to keep widows off of the streets.[50] Even though women claimed more power over property in this period, the disappearing ecclesiastical protections associated with the Reformation meant increased “dependence on their men’s goodwill.”[51] Considering the gendered applications of proprietary ownership and inheritance practices in the later sixteenth century, these findings lead to questions about the precedent of these trends in the early sixteenth century and how they may manifest themselves in a much smaller sample of wills from noble female testators of a particular region.

Methodology

The wills in this sample come from the Somerset Wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1501-1569, published by the Somerset Record Society in Volume 102. The collection includes 221 wills proven in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, copied from eleven different registers: Welles, Chaynay, Mellershe, Loftes, Streate, Chayre, Stevenson, Crymes and Morrison, Stonard, Babington, and Sheffelde. The bequests and property ownership revealed in each will often reflect each county’s manufacturing expertise or prominent trade. The testators in this sample would have been of comparatively elite status, although less than half indicated their status in their will through descriptive tags like knights, esquires, or gentlemen (see Appendix A).[52] Twenty-five testators in the sample were women, twelve of whom explicitly indicated their status as “widows” to potentially proclaim their intent to honor the requests of their late husbands to remain unmarried.[53] This volume includes wills proven throughout the rulership of Edward VI to the first decade of the reign of Elizabeth I; however, the dates of creation of wills in this sample range from 1558 to 1569, confined to the reign of Elizabeth I.[54]

The sample of wills utilized for this research consists of all twenty-five wills of female testators included in the volume, identified by their denotation as “widows,” historically female names, or the use of indicatively gendered language in the case of gender-neutral names. To adequately compare genders within localities, I selected twenty-five wills of male testators from the volume with an equivalent distribution across registers to that of the female sample. The male testator wills in this sample were selected based on their comparative length, type,[55] and creation date compared to female wills from the same register. Of the eleven registers in the volume, all but one–the Stonard Register–include at least one female testator; consequently, the Stonard Register is omitted from the sample.

The Introduction to Somerset Wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury categorizes the wills in the volume into two general types: simple documents listing the itemized bequests of the testator, including specific moveable objects or in-depth documents featuring directions for the future of the testator’s surviving kin and real property without mention of particular moveables.[56] The latter kind is associated with the participatory influence of lawyers, although all wills in the volume follow the same general structure.[57] Typically, an early modern English will begins with the testator’s name, occupation, and place of residence, followed by a religious invocation to God to accept their soul.[58] From there, testators list several specific bequests of proprietary items (moveable or real), money, or both to named beneficiaries. In many of these bequests, the beneficiaries’ relationship to the testator is stated; for example, “Item I give to Marie Wood my doughter [twenty pounds] and a Crocke and a panne.”[59] Although every will in the sample indicated bequests to at least one relative or servant, not every beneficiary was given a designative relationship title. No additional research was conducted into the possible relationship between those named in the wills if no title was given. As such, the preciseness of this research is limited by the strong likelihood that some beneficiaries named in the wills in this sample may have a familial relationship to testators that is not stated and, therefore, unaccounted for in the data.

Analysis of each will in the sample focused on the number and quantity of religious bequests, secular charitable bequests, bequests to male and female beneficiaries, bequests to other beneficiary groups, and special inclusions or requests. Religious bequests typically include money allotted for the maintenance and upkeep of the Wells Cathedral or “mother church in Welles,” as well as a donation to their local parish. In this sample, secular charitable bequests refer to money bequeathed to the local poor and for public works benefitting the general community. Bequests to male and female beneficiaries were tracked separately across wills in order to extrapolate gendered trends in bequeathing. Other beneficiaries include bequests made to groups or non-gendered individuals such as godchildren, household servants, and other non-relatives’ children. Special requests made in wills demonstrated the document’s utility by setting provisions that were not standard, suggesting the testator’s desires beyond the disposal of their possessions. These requests often included instructions for the stewardship of wealth or belongings before an under-age beneficiary was to receive them, addressed debts, or set conditions for inheritance if a surviving spouse remarried.

Findings and Discussion

The analysis of early modern English wills reveals the complex interplay between gender, religious transformation associated with the Reformation, and the developing utility and accessibility of inheritance practices. As testators navigated personal and societal obligations through their bequests, underlying themes surfaced, allowing the modern historian to speculate about testators’ intentions and the historical influences involved. The following sections examine how shifting societal values shaped testamentary decisions about charity, how men and women approached will-making in terms of bequests, the range of beneficiaries selected, and the utility of wills beyond the disposal of goods.

For the purpose of discussion and data presentation, all monetary amounts are represented in graphs using English pence to account for the pre-decimalized British currency system that existed until 1971.[60] The wills in this sample quantify currency using pence, shillings, pounds, and marks. The reader should note that in the antiquated British currency system, there are twelve pence in a shilling, twenty shillings in one pound, and thirteen shillings and four pence in one mark. Additionally, if the year of the will’s creation is unknown or listed as one of two consecutive years, the earlier year is used.

Religious Bequests

As previously mentioned, religious bequests remained a central aspect of will-making in early modern England, even though its prominence evolved in response to the Reformation. Only six out of fifty of the wills in this sample neglected to bequeath to any religious organization. Men were likelier to opt out of religious charitable bequeathing, as only two of those who chose not to bequeath to the church were women. In most cases where religious bequests were made, testators gifted a more significant sum to their local parish than the Welles Cathedral, presumably reflecting their loyalty to their local place of worship and immediate religious community. The customary donation to the Cathedral appears to be between four and twelve pence, although some gave more. Of those who made religious bequests, the total sum of their religious bequests ranged from two pence to Saint Andrew’s in Welles from Alice Dunne in 1560 to twenty-one pounds (5,040 pence) to “the parsone,” or parish priest, from William Trippe in 1568.[61] Trippe’s bequest is a clear outlier in the sample, skewing the data to the extent that it was removed from the graph to not drastically impair the overall trend in the data.

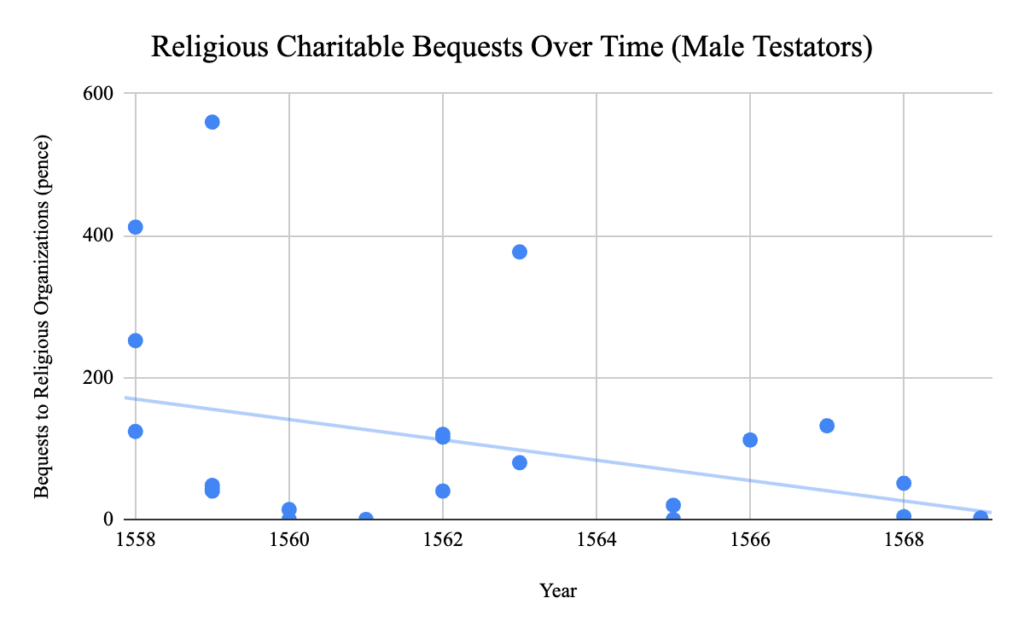

As shown in Figure 1, charitable bequests from male testators in this sample trended downwards in the ten years between 1558 and 1568, consistent with previous historians’ findings. On average, male testators gave only two pence more (108 pence) than their female counterparts (106 pence). Their bequests to charitable organizations tended to follow the typical format, including payment for burial expenses to their local church and a lesser donation to the Cathedral in Welles. Some male testators opted to give to multiple parishes; for example, William Trippe, mentioned previously, made a monetary donation of four pence to the Church of Welles and donated a bushel of wheat each to four other parishes.[62] Another unique bequest to the church came from William Hayne in the form of a yearly payment to the church of three pounds, six shillings, and eight pence for ten years.[63] Hayne wanted his donation to go towards the “mayntenaunce of singing gods service… not that yt shall hellp to discharge the parish for clarks wages,” instructing his overseers to make sure his donation did not go to clerical expenses.[64] Hayne may have opted for a staggered release of funds to prolong the memory of his charity to the church and included specific instructions for its allocation to ensure that his donations be used as he desired.

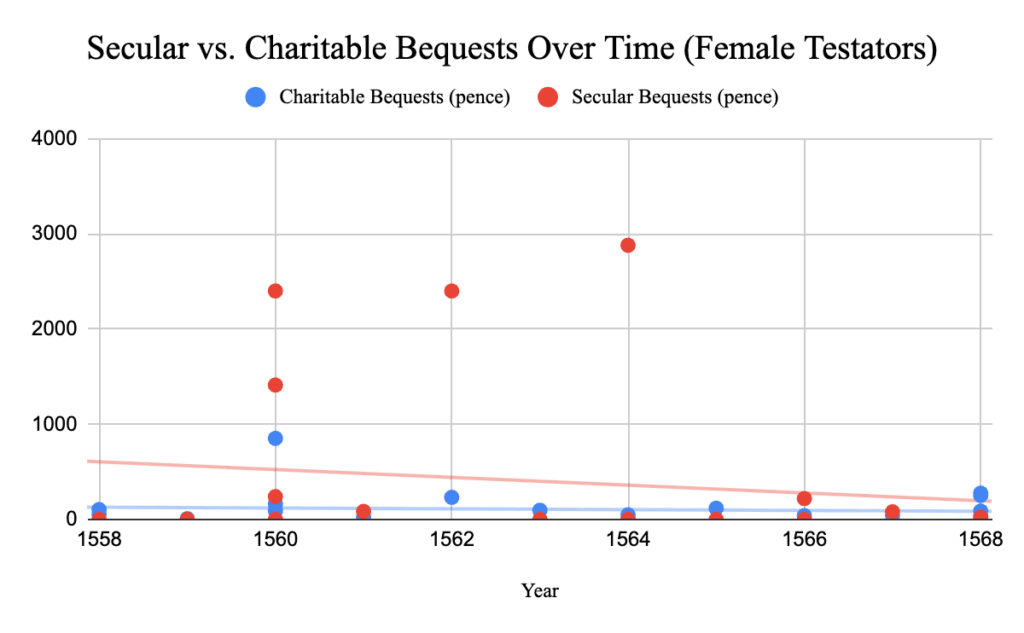

Female testators were slightly more consistent with how much money they bequeathed to religious organizations than male testators. Women in this sample bequeathed only monetary gifts to churches and religious figures, while male testators sometimes bequeathed other goods like bushels of wheat and malt.[65] As shown in Figure 2, religious bequests among women in this sample trended downward at a slightly lesser rate than that of male testators, perhaps indicating higher retention of spiritual devotion or gendered social expectations about piety and charity in women. As seen in Figure 2, Joan Combe’s will created in 1560 emerges as an outlier due to her donations of three pounds, six shillings, and eight pence to the Church in Welles, and four shillings and four pence to the churchwardens for the reparations of her parish.[66] Combe’s will demonstrates exceptional religious devotion, including a uniquely long religious prologue and extravagant wealth evidenced by a large number of bequests of considerable value. Typically, female testators stuck to the typical model, focusing on the Cathedral Church and their local parish. Like the men in this sample, some women chose to give to more than one church; for example, Alice Underhaye bequeathed to five different churches, as well as the vicar of St. Mary Magdalene.[67] As such, the religious bequests made and the agency taken in those bequests were comparable across male and female wills in this sample.

Secular Charitable Bequests

As opposed to charitable bequests to religious organizations, secular charitable bequests in this sample include gifts to the local poor and public works. Although we cannot separate any testator’s motives for a charitable bequest from their religious orientation, the differentiation testators made between religious organizations and community recipients is significant. Rather than making all of their philanthropic bequests through a church, thus leaving their donations to the discretion of clergy, twenty-one out of fifty testators made bequests specifically to some members of or public work in the community. The most common recipients of this type of bequest were the “local poor” or “parish poor.” Distinguishing the settled and “deserving” poor in the community as recipients of aid reflects commonly held early-modern ideas about the criminality of vagrant poor and the unwillingness to accept social responsibility for foreigners; this sentiment is demonstrated by the 1547 Vagrancy Act, which criminalized any able-bodied person who did not work by branding them with a V and sentencing them to slavery for two years.[68] Unlike religious bequests, secular charity lacked a normalized framework, allowing testators to imagine a legacy in their community through more innovative bequests.

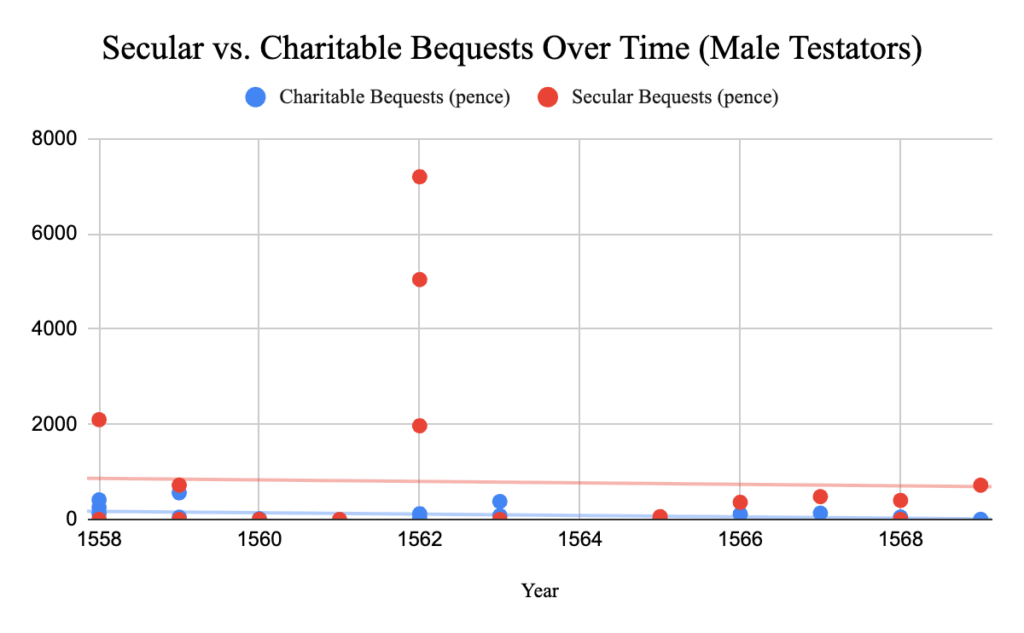

For the purpose of comparative analysis, data pertaining to secular bequests are displayed alongside charitable bequests data to discern whether there is any relationship between the established decrease in religious charitable bequests over time and other charitable bequeathing practices. The data for male and female testators show a gradual reduction in secular bequests over time, suggesting that all forms of charitable bequeathing gradually decreased in this period. Notably, the graphs reveal that when a testator did make a secular philanthropic bequest, the amount bequeathed was much higher, on average, than that of religious bequests in both male and female samples. I hypothesize that testators often bequeathed much greater amounts to secular charitable causes because they observed the issues in their communities first-hand, leading to a realistic understanding of donations that might be needed and because testators wanted to leave legacies amongst people familiar with them in life. Both scatter plots reveal a much more significant fluctuation in values for secular charitable bequests than religious bequests, suggesting that secular religious bequeathing was a much less standardized practice. Because less than half of the testators in the sample made secular charitable bequests and almost ninety percent of testators made religious bequests, the quantifiable data available for concluding the relationship between secular charitable bequests and time are much fewer.

Male testators in this sample made more non-religious charitable bequests than women (twelve compared to nine). As shown in Figure 3, the relationship between secular bequests made by male testators in the sample and time decreased at a rate very comparable to the observed decrease incharitable bequests over time. Furthermore, the data points representing secular bequests demonstrate much greater variability than the charitable bequest data, as shown by a range of y-values twice as great as that used for the female sample (8000 compared to 4000 pence).[69] The average value of male secular gifts in this sample was 795 pence, dwarfing the 390 women gave on average. The sheer wealth communicated by the wills of some male testators in this sample suggests that they held more wealth as a group, which could account for this difference. The greatest secular charitable bequest in this sample was made by William Leonard, a merchant, in the form of twenty pounds to be distributed to the parish poor at the discretion of his overseers and ten pounds towards the paving of the “high Streete” of his local town of Taunton.[70] Leonard’s will demonstrates substantial wealth and landholdings through his other bequests, so it is interesting that he only gives ten shillings to any religious institution in the name of “repairacions of the saide Church of Saint Magdalen.”[71] Leonard’s pattern of bequests suggests a focus on transferring wealth to familial and communal beneficiaries, perhaps to benefit people and causes he most valued in life.

Eleven of the twelve male testators who made secular charitable donations also made religious charitable bequests; John Coxe was the only male testator in this sample who neglected to make a religious gift in addition to his secular charitable bequest “towardes the relefe of the poore people of Chepenham [three shillings, four pence].”[72] Compared to other wills in the sample, Coxe’s will is very short and straightforward but also includes a heartfelt, custom religious invocation bequeathing his soul to God, discouraging conclusions that his lack of religious bequests correlated to an anti-religious stance. Other notable secular bequests made in the male sample included William Hayne’s very specific allocations of four pounds to the local poor, enough material to clothe five poor people for six years, a yearly donation to a particular almes house, donations to the “poore persones of Yevill Chester” at several terms, and twenty shillings to five poor maidens on their wedding days.[73] William Tanner’s data are omitted from the sample due to the inability to quantify his secular charity, which he willed in the form of a banquet for the poor; Tanner’s instructions read, “at the daye of my burrial that all suche poore people as shall come thereto shall have sufficient mete and drinke, and a penny a pece of them where nede ys.”[74] Consequently, male testators in this sample made unique terms for their secular charity, likely to address the problem of the poor how they thought best.

Compared to male testators, female testators in this sample made secular bequests less frequently, and when they did, they were of lesser value. However, women did make special terms for their secular bequests at least as often as men did, indicating a similar interest in tailoring their bequests to particular beneficiaries. As shown in Figure 4, secular bequests seem to decrease over time at a higher rate than charitable bequests, indicating a less established practice. Like the male sample, many secular bequest amounts are much greater than the religious bequests, indicating a greater allocation of funds when testators opted to make secular charitable donations.

Alice Rogers made the largest secular charitable bequest of the female sample in 1564 through her donations of ten pounds to twenty poor widows of Welles “with Wollen and lynnen clothes,” forty shillings to the “poore householders” of Welles, all of her “wood and Cole” to the poor people of Welles, and an additional ten pounds to poor widows in Welles.[75] Rogers’ focus on widows and “poor householders” may reflect a desire to address economic hardships facing dependents in early modern England, possibly accounting for a lack of support from male breadwinners due to joblessness, poverty, or widowhood. In her will, Joan Combe willed the distribution of three pounds, six shillings, and eight pence to the “poore people” on the day of her burial, six pence to every local head of household “gentlemen only excepted,” and fifty-one shillings to the repair of the local causeway.[76] Accounting for early modern spelling and social norms, Combe likely gifted only to male heads of household to observe coverture laws where wives were involved and reinforce the family unit under a male patriarch following popular beliefs about respectable charity. Other notable bequests include Agnes Roswell’s inclusion of bequests to poor from four different localities and Alice Worthe’s donation of “a quarter of beefe with fyve bushelles of barlie malte” to be distributed to the poor next Christmas.[77] Overall, when women did make secular donations in their wills, they were keenly interested in reinforcing the family unit under male patriarchs, perhaps reflecting their experiences under common law coverture or adhering to socially respected giving practices.

Non-Monetary Moveable Bequests

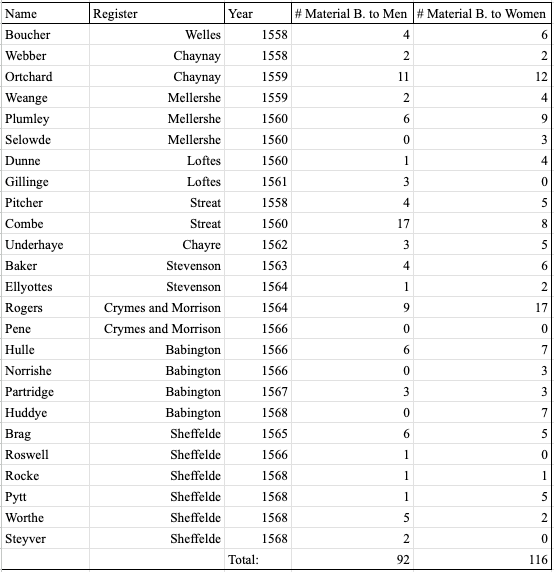

In this sample, moveable bequests included various goods ranging from silverware and clothing items to livestock and raw mercantile materials. For this research, only bequests featuring non-monetary moveable property were counted in order to extrapolate trends regarding the bequests of moveable goods most commonly given to women versus real property given to men.[78] The most frequently featured non-monetary goods were bedsteads, mattresses (“featherbeds”) and related dressings, silver spoons, cookware, gowns and “kirtles,” and singular livestock animals, such as ewes and mares. For data collection in this sample, a “bequest” refers to allotting one or more goods in a few sentences to a single beneficiary instead of many itemized bequests to one beneficiary. For example, “Item I give to John Score [two] platters [two] candlesticks and a Chafing dishe,” would be considered one bequest of multiple moveable items made by John Garratt in 1559 to a man of unnamed relation.[79] The scope of this paper does not allow for speculation about the monetary value of moveable bequests in this sample; as such, it is important to note that the actual worth of each bequest may vary significantly.

A typical bequest in this sample could range from gifting a single item of clothing to an extensive list of items spanning household, mercantile, and monetary categories of goods. A will’s type and extensiveness provide context for interpreting a single bequest. For example, in a comparatively short and uncomplicated will, like that of Richard Borde, his bequest of a featherbed, blankets, sheets, a coverlet, as well as money to buy the family farm to his daughter, Johane, is significant because it is the only bequest of moveable property he makes. [80] The sum of Borde’s monetary bequests indicates that he had some wealth, so his lack of material bequests could indicate a lack of personal value bestowed upon moveable goods or the inability to list extensive bequests due to declining health, among other things. Of household moveables, beds were the most valuable pieces of furniture, so they most often went to children or close family members.[81] Conversely, in a lengthy will facilitating a large number of moveable bequests, such as Joan Combe’s will, a comparable bequest of a featherbed, bolster, sheets, and a coverlet to her servant, Johan, has a much different character.[82] Analyzing Combe’s bequests to her other servants, the previously-mentioned bequest ranks far below bequests to other highly-favored servants who received an additional ten pounds in cattle or 100 marks.[83]

Most bequests with many items listed included many individually named household items. In some cases, material goods were bequeathed in collections; for example, Eleanor Baker bequeathed “all my werynge apparrell” to her daughter.[84] Specific items meant for one person were sometimes distinguished from other similar items using adjectives to describe their quality and perhaps indicate degrees of sentimentality. William Manshippe bequeathed his “mothers best kyrtle” and Agnes Plumley gave her “seconde best beades.”[85] Historians can speculate about the reasoning behind certain bequests, considering their focus on specific items of potential use or value to a beneficiary instead of multiple items described only in terms of their monetary value. Some testators also applied conditions or future transfer dates to bequests; William Rosewell bequeathed his daughter, Johanne, “the value of Twentye nobles” in sheep and cattle on her wedding day, likely as a dowry.[86] In this sample, the Sheffelde register stands out as an agricultural county wherein most wills included bequests of agricultural goods such as wool and livestock. When bequeathing livestock, testators in this sample commonly bequeathed exact numbers of a type of animal (e.g., three sheep), sometimes specifying the animal’s age, gender, or color.

Additionally, the itemized sum of specific moveable bequests does not necessarily represent a testator’s substantial moveable property. Moveable property not explicitly listed may be accounted for by the “residue” often left to the will’s executor. In most cases, female testators in this sample made their son(s) their executors (sixteen out of twenty-five). The next most popular option was other trusted men jointly (six out of twenty-five). The only female executrixes named by women were appointed by Edith Pitcher, who had five daughters and no sons, in 1558/9.[87] In the male sample, the leading choices of executor were wives (ten out of twenty-five), son(s) (six out of twenty-five), followed by wife and child jointly (four out of twenty-five). Interestingly, men were likelier to name at least one woman as executrix than women. However, an executorial nomination could be received as a significant burden requiring the stewardship of devoted female kin instead of busy male breadwinners; consequently, executorship should not necessarily be interpreted as a promotional tool for female kin.

The number of personal bequests of moveable goods made by male and female testators to recipients of different genders is relevant to the study of bequeathing practices in sixteenth century England because it provides some insight into the focus of a testator’s transfer of wealth and property. Amy Louise Erickson notes that “despite the truism that land was the basis of wealth in an agricultural society, replaced by cash and financial assets in a commercial, industrial society, the relative value of land and moveables on an ordinary household scale was actually much closer than it is today.”[88] While this may not apply to elite households to the same degree, as many testators in the sample listed multiple real property holdings, the value of moveable property should not be overlooked, considering the value of commercial and livestock property in mercantile counties such as these. It is also reasonable to assume that the sample testators’ wealth would positively relate to the value of household moveable property in their possession. Therefore, the bequests of moveable property in many of these wills can be considered a substantial and intentional transfer of value to a chosen beneficiary.

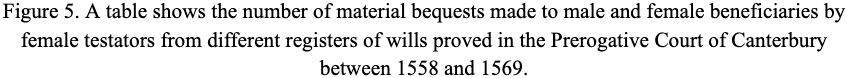

In the study of personal bequests made by female testators in this sample, most women named more female beneficiaries than male in their wills. As seen in Figure 5, testators who made fewer bequests overall displayed a comparatively even distribution of bequests between genders. Interestingly, testators who made a more significant number of bequests exhibited a more asymmetric distribution between genders, not uniformly favoring one over the other. One explanation for this is that testators who made a large number of bequests demonstrated a focus on disseminating as much moveable property as possible, often gifting the same grouping of items (ex., silver spoons, pod-dingers, pan)–or slight variations–within the same category (household, agricultural, etc.) over and over to beneficiaries of the same gender depending on what was the bulk of their moveable property.

Joan Combe’s will, created in 1560, stands out as overwhelmingly focused on men as recipients of moveable property. Looking closer, many of her named beneficiaries of moveable goods are her male servants (mentioned previously), to whom she is bequeathing household items such as featherbeds and sheets, presumably used during their service to her household. One of Combe’s servants stands out as the recipient of ten pounds in money or cattle, silverware, a featherbed, a flock bed, pewter garnish, candlesticks, and a coffer, among other things.[89] Another servant receives a featherbed, sheets, and blankets.[90] As the widowed head of household, we can assume that Combe is preparing to dissolve her staff upon her death and aims to provide them with the means to move on. In addition to these material bequests, Combe further provides for the future of her staff by giving “to every servaunt that shall happen to be with me at my decease taking Wagis of me one Whole yeres Wagis.”[91] Unlike many other female testators in this sample, Combe also includes a custom testamentary preamble:

And for as much as muche also as the principall care and studdy of every true christian man and woman sholde be to lerne to die well for the whiche purpose it is most expedient and necessarie that every man and woman sholde discharge the business of worldely thinges in tyme of helthe to the intente that in tyme of deth and final sicknes they maye wholye applie and give them selves to gostly and spirituall matters for the welth of eternal ioye and not be occupied with worldly and temporall things.[92]

Combe’s profession about disposing of her earthly possessions mirrors the clergy’s historical encouragement of parishioners to create wills and bequeath generously to benefit their souls in the afterlife. As previously mentioned, Combe’s will features the largest religious bequest in the female sample and notable secular bequests to the poor and public works. Her generosity in bequeathing moveable property to secular individuals and her stance on disposing of earthly possessions suggest that her religious motivations extend beyond her charitable bequests.

Comparatively, male testators made a significantly smaller number of bequests than female testators (see Figure 6). The distribution of moveable bequests between males and females is comparable in any given will. Men in the sample bequeathed zero moveable goods to one gender or both twice as often as female testators. Male testators bequeathed to male beneficiaries more often than females; however, the difference between bequests to male and female beneficiaries was smaller than that of the female sample. Most moveable bequests by male testators included apparel, mercantile and agricultural tools and goods, and livestock. It is important to note that male testators in this sample used their wills at a far greater frequency than women to devise land separate from moveables in this analysis.

Real Property Bequests

Real property devises made through wills in this sample include burgage plots, tenements, appurtenances, houses, inherited rent on land, and lease and interest in land. Female testators bequeathed real property in only five instances and only once to a female recipient; in 1564, Eme Elyottes devised “half the land” for her eldest daughter and the other half for her son.[93] Interestingly, both children received the same stipulation to pay half of the farm rent to the “Lord yerely” and twenty shillings to support her youngest daughter, Mary.[94] Consequently, female testators shared some traditional male desire to keep property in the family. Edith Hull’s will, created in 1566, bequeaths her eldest son a “panne” and stipulates that it must stay in the male lineage to “remayne to alwayes the Names of the Hulles.”[95] Here, Hull attributes the same patronymic sentiment usually affixed to real property to a moveable object, suggesting immense personal importance.

Real property bequests were featured in eleven of twenty-five male wills. Of these, five bequests were made to men, and six were made to women. Most female beneficiaries were the wives of male testators, often receiving the houses they occupied for the rest of their lives or other lands with the stipulation that the deed transfer to the eldest son if his widow remarried. For example, William Selwood’s will includes the instructions to transfer a burgage left to his widow to his son if she remarries: he says, “yf that she happen to marry, that then my foresaide dwelling house with the foresaide burgage called Balrens heyes shall remaine Unto my sonne….”[96] Walter Doble’s 1565/6 will left the lease and interest in land to his only biological child, his daughter Julyan, favoring her over his wife’s three sons from a previous union–who received three sheep each.[97] In his will, Harry Lancaster named his brothers-in-law as overseers of the lands and cattle until his daughters came of age or married.[98] Therefore, the perceived kinship between a testator and his biological daughter could supersede the presence of non-biological sons, raising questions about early modern English inheritance patterns when stepchildren were involved. Notably, the devising practices of men in this sample seem to divert from trends observed by Amy Louise Erickson.

Types of Beneficiaries

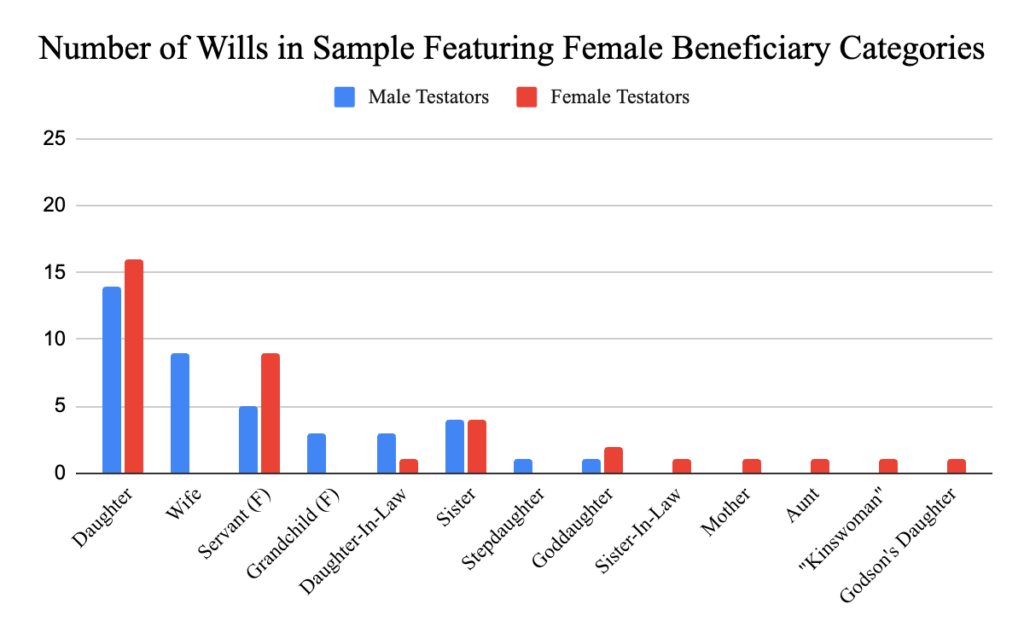

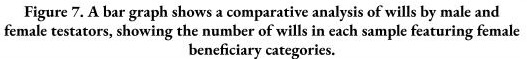

Analyzing the types of beneficiaries listed in this sample helps to extrapolate gendered trends in testators’ creation of “bequeathing networks,” or groups of people whom testators considered for the benefit of wealth transfer in this period. As seen in Figure 7, female testators mentioned female beneficiaries more frequently and in more relationship categories than male testators. However, male testators did include granddaughters and daughters-in-law more often than female testators. While male testators mentioned a smaller range of relationship categories in their wills, we know that the actual number of bequests made to male or female individuals is comparable in individual wills.

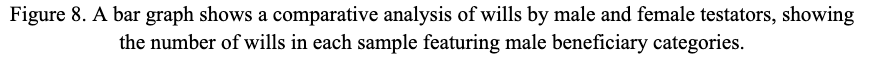

Considering mentions of male beneficiaries with indicative relationship titles, male testators included a broader collection of relationship categories than female testators, as seen in Figure 8 (eleven to eight). Of the twenty-five female wills in this sample, male beneficiary designations were mentioned in more wills than in the male sample; however, it is critical to note that female testators made almost twice the number of bequests overall. These data support Amy Louise Erickson’s conclusion about the tendency of female testators to favor female beneficiaries. However, the data also suggest that men included a comparable array of male beneficiaries in their network of kinship bequests to those created by women.

Considering individual wills, no single female testator stands out as having created an exceptional network of bequests to either gender; bequests featuring kin are scattered throughout wills by female testators in this sample. Alice Plumley’s will features a comparably extensive group of male kin, made up of her brother-in-law, brother, son-in-law, and godson.[99] Eyde Brag bequeathed to her godson’s daughter, perhaps the most far-removed relationship category featured in the data, but that was the only female kinship category she included in addition to her godson and brother–probably indicating a close relationship.[100] Alice Rogers included a notable distribution of female kinship categories in her will, including her sister, aunt, female servant, and kinswoman.[101] Rogers made most of her bequests to female beneficiaries, but her network of male kin was roughly the same size because she included her godson, son, and brother.[102]

Similarly, bequests featuring kinship categories of both genders are scattered throughout male wills in this sample. Thomas Dier included a comparatively high number of male kinship categories by bequeathing to his sons, nephew, and male servants.[103] The only female beneficiaries Dier named were his daughters.[104] William Hayne created a notable network of female beneficiaries by including his granddaughters, female servants, and wife, in addition to his sons and grandsons.[105] As previously discussed, William Leonard focused on relatives, naming only family members as beneficiaries; he included his sons, brother, male servants, daughters, stepdaughters, sister, and wife.[106]

Consequently, the gender of a testator is not a reliable indicator of what kinds of kin will be included in their will. While testators in this sample included more categories of kin of their respective genders, the data are scattered throughout the wills. Additionally, these data depend on the unknown types of kin testators in the sample had to choose from. These data are helpful for observing the range of individuals with named relation to the testator included as beneficiaries, suggesting that male and female testators made comparable kinship networks through bequeathing practices.

Other Beneficiaries

Other categories of beneficiaries commonly featured in wills in this sample were purposely separated from the gendered analysis of beneficiaries due to a lack of gender specification, a general group distinction, or both. For example, most testators across both genders bequeathed to “godchildren.” Godchildren commonly received four or twelve pence each, sometimes getting equal numbers of livestock or other moveables. Other common beneficiaries of this kind include “household servants” and the children of some named person in their lives or communities.

Although no meaningful trends emerged concerning bequests to godchildren and servants, male testators were three times more likely to bequeath to the children of some named person of unknown relation in their will. In the female sample, Alice Underhaye is the only testator to provide for a person of unknown relation’s children; she bequeathed forty shillings to the “children of William Chappell.”[107] In the male sample, John Fitzrichard, Robert Williams, and William Trippe all left money to someone else’s children without any further instruction besides reallocation among the children if one of them were to die.[108] Robert Williams notably bequeathed to the children of both John Hollacombe six shillings, eight pence, and the children of John Whether twelve pence each.[109] The inclusion of children of people with unknown relation to the testator is interesting because it suggests a sense of responsibility or outlet for charity, which male testators acknowledged more than female testators in this sample.

Special Provisions and Requests

Special requests made by testators in this sample demonstrate the utility of wills beyond the disposal of goods. Analyzing these requests and stipulations as purposefully added elements to an otherwise fairly boilerplate document allows for speculation about the personal desires and values of the testators. The most typical special requests and instructions featured in this sample relate to the stewardship over goods and land intended for beneficiaries currently underage or unmarried women. Occasionally, special requests would direct some agent of the will to collect debts owed to the testator and redistribute them to beneficiaries. The most notable special requests in this sample relate to amounts set aside for specific purposes and special considerations for the care of beneficiaries beyond wealth transfer in the will.

From the women’s sample, Mary Huddye leaves the residue of all her goods and cattle to her two sons and names them as her executors.[110] She then instructs her sons further:

Charging them upon the blessinge of god that they do love and lyve to geather as brethren ought to do and to be good loving and gentle Unto their poore Syster charging them as they will obteyn the blessing of godd and to avoyde godes terryble wrathe that theye do paye and deliver unto theyre poore syster her sayde porcion of one hundredthe markes without anye collusion or Decepte.[111]

Mary Huddye’s purposeful inclusion of this excerpt speaks to her awareness and concern for the inequalities created by traditional inheritance practices based on gender. In the context of her generosity to her two sons, she appeals to their fair treatment of her daughter, instructing them to provide for her “meat, drincke, and apparel” until she reaches the age of twenty or is married, whichever comes first.[112] Terms like these show up very rarely in this sample of wills; still, they speak to the auxiliary potential of these documents and attest to the special consideration of certain vulnerable kin.

From the men’s sample, William Tanner’s will stands out for his provision that the residue of his goods be split between his son and his grandchildren, provided that his son behave a certain way.[113]

But yf John my sonne doe not frame hymselfe as an honest man with such gooddes as I bequeathed hym to the increasinge of hit but take his pleasure and be ryotus and Lyberall and take no care for the tyme to come for the honeste maintenamce of hym and his Children, then that my Will is that he shall have but the tenn pound that I bequeathed hym…[114]

Here, Tanner’s testamentary inclusion acts as a check and balance on his son’s authority as a joint executor, tasking overseers with the discretionary ability to limit his inheritance. The additional step William Tanner makes in his will to ensure grandchildren are taken care of by his legacy mirrors Mary Huddye’s concern about the potential for misuse of power or a lack of adherence to the testator’s instructions. As such, the special requests and provisions present in wills in this sample speak to a shared awareness and concern for more vulnerable individuals in their kinship networks.

Conclusion

This analysis yielded significant insights into the bequeathing practices of Somerset’s elite men and women, allowing us to draw conclusions about gendered differences in property transfer and changes in the context of the ongoing English Reformation. With decreased clerical involvement and the standardization of inheritance practices such as the written will, English testators developed their will-making practices to reflect changing social values and observe specific desires for their legacies on earth.

Considering Amy Louise Erickson’s findings about ordinary women in the century following the wills included in this sample, this research sought to speculate about similar trends in the will-making practices of elite women, who likely had more access and education pertaining to the creation of generational wealth. This research found many of the trends reported by Erickson to be true about women’s will-making practices, such as an overall preference for female beneficiaries of moveable goods and the creation of an extensive female network of kinship bequests. I also found evidence that male and female testators considered the implications of women’s dependence on men’s goodwill during this period, creating special instructions to prevent male beneficiaries from neglecting female kin. I did not expect to find that men included a comparable array of male kin in their bequest networks, expanding their bequests significantly beyond their sons, the most apparent vessels for the family legacy.

Regarding religious charitable bequests, these data support conclusions previously made by historians suggesting that testators were becoming less concerned with end-of-life charity for religious institutions to safeguard their souls; however, male and female testators in this sample still exhibited individual preferences in their religious bequests, including multiple organizations and stipulating various allocations. Women testators remained more consistent with their religious bequests over time, which could pertain to gendered societal expectations about piety and charity in women. Regarding non-monetary moveable bequests, women tended to focus on female beneficiaries and listed almost twice as many moveable bequests as men. Some women in the sample donned religious attitudes and motivations about the general disposing of their moveable goods, suggesting that these bequests may have served as a pious charity in themselves.

Despite my hypothesis that secular bequeathing would increase in light of decreasing charitable bequests, both samples demonstrated a declining rate of secular charity to communal recipients over the ten-year period. Although secular charitable bequests yielded fewer data than religious bequests, the information suggests that when both men and women gifted to communal beneficiaries, they allocated much larger amounts on average and included incredibly specific instructions for the distribution. Examples of secular charity by male and female testators demonstrated how testators circumvented churches in order to address social ills how they saw fit. By doing so, testators also avoided the anonymity and uniformity of religious donations and the possibility that the clergy would misuse their donations for administrative purposes. Female testators demonstrated elevated concern for both widows and heads of household, perhaps adhering to socially acceptable categories of charity. Through secular charitable bequeathing, testators in this sample exemplified the opportunities for expression and legacy-creation through wealth transfer.

Men devised more real property than women and more real property to women than men, diverting from Erickson’s general observation about male devising trends. Many men chose to devise to wives and daughters even when sons were present; however, male testators’ desire to keep real property in the family name can be observed through special requirements willing property to male heirs if a widow remarried. In some cases, female testators demonstrated a similar desire to keep important property in the family; however, women testators applied this sentiment to both moveable and real property.

Considering other beneficiary groups separately from the gendered analysis, we can conclude that both male and female testators accepted responsibility for the future of godchildren and servants in their end-of-life wealth transfers. Interestingly, male testators also sometimes took another opportunity to make charitable donations to the children of person(s) of unknown relation in their wills. Another area where testators of both genders utilized discretion in the will-making process was to regulate the potential misuse of property or failure to observe the terms of their will. Both male and female testators took special care to provide instructions for the care of less societally advantaged beneficiaries–namely female family members–sometimes terminating some bequest to male agents in the will if they failed to honor the testator’s wishes. In other cases, they appealed to their kin’s morality and religious observance to do the right thing. This phenomenon suggests a collective understanding of the gendered equality created and sustained by early modern inheritance practices and the desire to circumvent that reality for cherished women in their lives.

This research provides a valuable case study that demonstrates trends in real-life will-making practices in early modern Europe. The findings confirm and diverge from preconceived notions about what a gendered analysis of documents of this period might look like. Further research is required to answer remaining questions about bequeathing preferences involving stepchildren, the bequeathing practices of ordinary women and children before Amy Louise Erickson’s inquiry, and evidentiary gaps about beneficiary choices where family information is available in the case of elite testators.

Appendix A. Wills from Somerset Volume 102 in this sample.

| Register | Testator Name | Title (If Included) | Year of Will Creation | Page Number in Volume |

| Welles | Harry Lancaster | 1558 | 1 | |

| Welles | Margery Boucher | Widow | 1558/9 | 4 |

| Chaynay | William Hayne | 1558/9 | 8 | |

| Chaynay | Anne Webber | Widow | 1558/9 | 13 |

| Chaynay | Agnes Ortchard | Widow | 1559 | 18 |

| Chaynay | John Fitzrichard | Gentleman | 1559 | 19 |

| Mellershe | Margery Weange | 1559 | 28 | |

| Mellershe | John Garratt | 1559 | 29 | |

| Mellershe | William Tanner | 1559 | 29 | |

| Mellershe | Agnes Plumley | Widow | 1560 | 32 |

| Mellershe | John Ashe | Esquire | 1560 | 36 |

| Mellershe | Elizabeth Selowde | Widow | 1560 | 37 |

| Loftes | William Selwood | 1559 | 41 | |

| Loftes | Alice Dunne | Widow | 1560 | 44 |

| Loftes | William Manshippe | 1560 | 45 | |

| Loftes | Joan Gillinge | Widow | 1561/2 | 47 |

| Streat | John Tomsyn | 1558 | 48 | |

| Streat | Edith Pitcher | 1558/9 | 50 | |

| Streat | Joan Combe | 1560 | 51 | |

| Streat | William Leonard | Merchant | 1562 | 61 |

| Chayre | Richard Harvye | 1562 | 72 | |

| Chayre | Alice Underhaye | 1562 | 74 | |

| Stevenson | John Downham | 1559 | 78 | |

| Stevenson | Eleanor Baker | 1563 | 84 | |

| Stevenson | Thomas Boundger | 1563 | 86 | |

| Stevenson | Eme Ellyottes | 1564 | 87 | |

| Crymes and Morrison | Thomas Dier | Knight | 1563 | 91 |

| Crymes and Morrison | Alice Rogers | Widow | 1564 | 92 |

| Crymes and Morrison | John Coxe | 1564/5 | 96 | |

| Crymes and Morrison | Anne Pene | 1566 | 105 | |

| Babington | John Harker | Smith | 1561 | 130 |

| Babington | Robert Williams | Yeoman | 1562 | 131 |

| Babington | Edith Hull | 1566 | 132 | |

| Babington | Elynor Norrishe | 1566/7 | 133 | |

| Babington | William Rosewell | Gentleman | 1567/8 | 138 |

| Babington | Agnes Partridge | Widow | 1567/8 | 139 |

| Babington | Mary Huddye | Widow | 1568 | 146 |

| Babington | William Trippe | Husbandman | 1568 | 148 |

| Sheffelde | Richard Borde | 1563/4 | 158 | |

| Sheffelde | Eyde Brag | 1565 | 160 | |

| Sheffelde | Walter Doble | 1565/6 | 162 | |

| Sheffelde | Richard Roswell | 1566 | 163 | |

| Sheffelde | Agnes Roswell | Widow | 1566/7 | 163 |

| Sheffelde | Elize Rocke | 1568 | 168 | |

| Sheffelde | Florence Pytt | Widow | 1568 | 169 |

| Sheffelde | Alice Worthe | 1568 | 172 | |

| Sheffelde | Robert Sesse | 1568 | 175 | |

| Sheffelde | John Sparke | Yeoman | 1568/9 | 178 |

| Sheffelde | Isabel Steyver | 1568/9 | 183 | |

| Sheffelde | John Alen | 1569[115] | 184 |

[1] Julia Drobish graduated from UC Santa Barbara in 2025 with a B.A. in History of Public Policy and Law. Julia’s interest in end-of-life transfer of wealth stems from her experience in wills & trusts gained through an internship while in college. She plans to pursue her JD and retain her passion for history.

[2] The Stuart L. Bernath Prize is awarded to the History undergraduate whose research paper is selected by the UCSB History Department Prizes Committee as the best paper produced in a one-quarter course.

[3] Colin J. Brett, ed., Somerset Wills From the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1501-1569 (Somerset Record Society, 2024), p. 183.

[4] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 183.

[5] Ralph Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” in Death, Religion, and the Family in England, 1480-1750 (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 81.

[6] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 81.

[7] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,”p. 82.

[8] “The Evolution of Wills and Trusts Over Time,” Westfield Wills, 22 June 2024, https://westfieldwills.co.uk/the-evolution-of-wills-and-trusts-over-time/.

[9] “Manuscripts and Special Collections,” University of Nottingham, accessed 25 February 2025, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deedsindepth/associated/will.aspx.

[10] Henry Bley-Vronan, “Inheritance Laws: England, 16th-18th Centuries,” accessed 25 February 2025, http://www.sls.hawaii.edu/bley-vroman/henry/EntailmentLaws.html.

[11] “Manuscripts and Special Collections.”

[12] Amy Louise Erickson, Women and Property in Early Modern England (Routledge, 1993), p. 3.

[13] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 84.

[14] “The Evolution of Wills and Trusts Over Time.”

[15]“The Evolution of Wills and Trusts Over Time.”

[16]“The Evolution of Wills and Trusts Over Time.”

[17] Robert N. Conners, “The Statute of Uses and Some of Its Important Effects.” Hastings Law Journal 1:1 (1949): p. 72.

[18] Conners, “The Statute of Uses,” p. 73.

[19] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. ix.

[20] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. ix.

[21] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 96.

[22]Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 96.

[23] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 97.

[24] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 97.

[25] Houlbrooke, “The Making of Wills,” p. 97.

[26] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. xi.

[27] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[28] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[29] Tom Arkell, “The Probate Process,” in When Death Do Us Part: Understanding and Interpreting the Probate Records of Early Modern England, ed. Tom Arkell, Nesta Evans, and Nigel Goose (Leopard’s Head Press Unlimited, 2000), p. 7.

[30] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[31] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[32] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[33] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. vii.

[34] Judith Ford, “A Study of Wills and Will-Making in the Period 1500-1533 with Special Reference to the Copy Wills in the Probate Registers of the Archdeacon of Bedford 1489-1533,” PhD thesis (The Open University, 1992), p. 2, https://oro.open.ac.uk/57388/1/DX175920.pdf.

[35] Ford, “A Study of Wills,” p. 3.

[36] Jeff Cox and Nancy Cox, “Probate 1500-1800: A System in Transition,” in When Death Do Us Part: Understanding and Interpreting the Probate Records of Early Modern England, ed. Tom Arkell, Nesta Evans, and Nigel Goose (Leopard’s Head Press Unlimited, 2000), p. 15.

[37] Cox and Cox, “Probate 1500-1800,” p. 19.

[38] Cox and Cox, “Probate 1500-1800,” p. 24.

[39] Cox and Cox, “Probate 1500-1800,” p. 24.

[40] J.D. Alsop, “Religious Preambles in Early Modern English Wills as Formulae,” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 40:1 (1989), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046900035405.

[41] Cox and Cox, “Probate 1500-1800,” p. 37.

[42] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. xi.

[43] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 223.

[44] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 12.

[45] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 19.

[46] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 19.

[47] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 19.

[48] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 228.

[49] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 227.

[50] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 227.

[51] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 19.

[52] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. x.

[53] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. x.

[54] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. ix.

[55] “Type” refers to the two distinct types of wills discussed in the next paragraph.

[56] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. viii.

[57] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. viii.

[58] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. viii.

[59] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 37.

[60] “Pounds, Shillings, and Pence,” The Royal Mint Museum, accessed 10 March 2025, https://www.royalmintmuseum.org.uk/journal/history/pounds-shillings-and-pence/#:~:text=The%20pre%2Ddecimal%20currency%20system,coinage%20system%20prior%20to%20decimalisation.

[61] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 44, 148.

[62] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 148.

[63] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 8.

[64] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 8.

[65] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 72.

[66] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 51.

[67] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 74.

[68] “Vagrancy, Heresy, and Treason in the 16th Century,” BBC.co.uk, accessed 20 March 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z2cqrwx/revision/2.

[69] The data outlier explained for Figure 1 (William Trippe, 1568) continues to be omitted in this data set to prevent a drastic skew in the Religious Bequests data.

[70] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 62-63.

[71] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 62.

[72] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 96.

[73] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 8.

[74] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 29.

[75] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 93-94.

[76] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 52.

[77] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 163, 172.

[78] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 19.

[79] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 29.

[80] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 158.

[81] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 65.

[82] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 51.

[83] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 51.

[84] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 85.

[85] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 32, 45.

[86] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 138.

[87] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 50.

[88] Erickson, Women and Property, p. 18.

[89] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 52.

[90] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 52.

[91] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 52.

[92] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 51.

[93] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 87.

[94] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 88.

[95] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 133.

[96] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 41.

[97] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 162.

[98] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 1.

[99] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 32.

[100] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 160.

[101] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 92.

[102] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 92.

[103] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 91.

[104] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 91.

[105] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 8.

[106] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 61.

[107] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 74.

[108] Brett, Somerset Wills, pp. 19, 131, 148.

[109] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 131.

[110] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 147.

[111] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 147.

[112] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 147.

[113] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 30.

[114] Brett, Somerset Wills, p. 30.

[115] No year of creation was given; here, the year proved is used.