Victory Without Conquest: Moral Authority and Empire in the Zafarnama

Hoonur Kaur

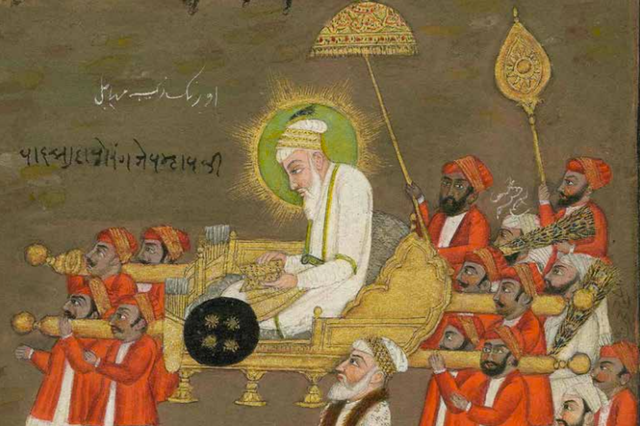

Alamgir, most commonly known as Aurangzeb, ruled the vast Mughal Empire from the late 17th to early 18th century, holding most of northern India under his control. He was missing a final, crucial territory to be truly fulfilled: the land of five rivers, Panjab. Unfortunately for him, Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh guru and founder and chief of the Khalsa army, planned to make that difficult for him.

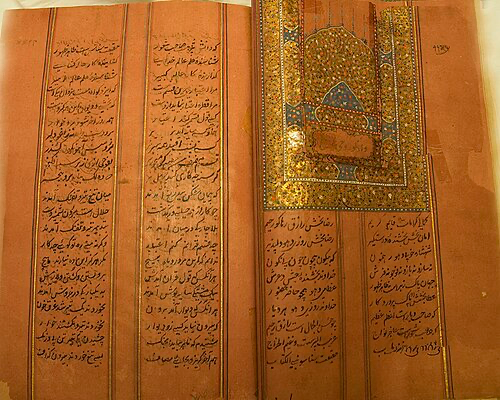

In December 1705, Guru Gobind sent a Persian letter to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, later known as the Zafarnama, the “Declaration of Victory.” Rather than celebrating military triumph, the letter stages a moral confrontation, accusing the emperor of betrayal, broken oaths, and spiritual failure. Read closely, the Zafarnama reveals less about the logistics of Mughal–Sikh warfare and more about how sovereignty, righteousness, and victory were understood by a Sikh leader fighting injustice instilled by the imperial power.

Totalling one hundred and eleven verses, the letter emphasizes rhyme and poetic tone, as the Guru wrote for militaristic needs as well as pleasure. It is rooted in a sequence of conflicts between the Mughal state and the Sikh community, but Guru Gobind Singh does not recount these events as neutral history. Instead, They reframe moments such as the evacuations of Anandpur, the Battle of Chamkaur, and the deaths of Their sons as evidence in a larger ethical indictment, and this reframing is crucial. Aurangzeb, often remembered in South Asian tradition as the most ruthless ruler of the Mughal Empire, does not appear in the Zafarnama as a distant tyrant or legendary villain. Rather, as an ordinary man who must be held accountable to divine law. Through poetic verse, the Guru transforms battlefield loss into spiritual victory. The letter insists that true kingship is measured not by conquered territory, including Panjab, but by adherence to truth (dharam) and honor. By addressing the emperor directly, Guru Gobind Singh reduces the distance between ruler and subject, battlefield and court, forcing Aurangzeb to confront the consequences of his actions not in history books, but in the afterlife.

Guru Gobind gave the letter to two of Their entrusted followers, Bhai Daya Singh and Bhai Dharam Singh. Both were members of the Panj Pyare, the first five Sikhs to be initiated into the Sikh Khalsa. Traveling on foot and horseback through Mughal-controlled territory in the aftermath of intense military conflict, the messengers faced the constant threat of arrest or execution. Legend has it that upon reading the letter, Aurangzeb’s heart stopped, and he fell dead in his bed. The Zafarnama killed him with the sheer weight of its righteousness and its call to introspection and guilt of conscience. Modern research predicts that he died of natural causes just days or weeks after the letter. However, those who follow Sikh tradition do not think that his death was simply a coincidence, believing that the “wretched” man died of shock in reflecting on his tragic faults. This is because Sikhism emphasizes divine justice and the consequences of a person’s moral wrongdoings, even if no action is taken against the criminal during their lifetime on Earth.

The Zafarnama is unintentionally divided into four parts, not by the Guru Themself, but by modern-day historians. The introduction of the letters greets Aurangzeb with praise to God, known to the Sikh faith as “Waheguru.” All glory is to God, the Guru writes with all intention and invocation to Waheguru. In doing so, Guru Gobind claims that the Almighty will correct all wrongs, for justice will be served in the next life if not in this one. Translated, the eighth verse claims, “The Lord is Omniscient, the Protector of the lowly; He, the Friend of the poor, is the Destroyer of the enemies”. The Guru is not saying that They wish for Waheguru to punish Aurangzeb, but instead that Waheguru will do what They have always done.

The second section focuses on a historical retelling that reminds Aurangzeb of his vile actions. The Guru reminds the Mughal Ruler that he betrayed his oath on the Qur‘an during the second Battle of Anandpur. During this betrayal, Aurangzeb placed his hand on the Holy Qur‘an and swore to let the Khalsa leave their Anandpur Killa (fort) peacefully, even as he seized the fort himself. Despite his promise, he attacked them, thereby committing both political and sacred betrayals. Following this action by writing, “I have no faith at all in such a person for whom the oath of the Quran has no significance.” The religious text their opponent could have followed did not matter to the Guru; what mattered was what the text would urge that person to do.

The Guru states, “Forty brave but hungry men, how are they expected to defend?” Surely, winning a battle unfairly is as terrible a fate as losing one. Similarly, Gobind shames the emperor in the third part of the Zafarnama. There are many lines in the Zafarnama in which the Guru writes favorably of Aurangzeb, calling him “the chief of chiefs” and “the master of the country and its wealth”. But these praises cannot be mentioned without his clear calamities. Aurangzeb is criticized for his cowardice in waging war against starved men, and for a deceitful and unfair victory. He is also portrayed as one who causes unreasonable and unjust bloodshed. Therefore, these charges against his actions illustrate that he could not possibly be a true worshipper of Allah, but instead a worshipper of gold and earthly objects.

The letter concludes by warning the emperor and advising him to be cautious in his next steps. They emphasize that God is the one who has planned out all of the triumphs and pitfalls of humanity. By not having God’s favor, one is bound to fail; “If the enemy brings thousands of his men against an individual, who has the protection of the Lord, not even the slightest harm will visit him”. In full, the letter reminds Aurangzeb that although his earthly kingdom is within his power, his judgment for his actions in the next life is beyond his control.

Aurangzeb’s legacy is known to have ended with his reading of the Zafarnama. Karma is a common theme in all Dharmic religions, and the fate of the longest-ruling emperor of the Muslim empire was no exception. Even if the legend of the sudden and immediate death is nothing more than a story, the fact remains that Aurangzeb did die soon after he read the letter. He was previously known to be ill; however, it was relevant that his guilt for unfairly causing so much pain to so many innocent people further sickened him. The day-to-day stress he dealt with in his newfound belief that he would not experience Jannat (the highest heaven for Muslims) after judgment day decreased his quality of life. It is important to note that while Aurangzeb is remembered as a tyrant in Sikh memory, some scholars portray him as a devout ruler who set aside Islamic law to pursue Islamic sovereignty. We are reminded by this that history is not made only by sequences of events, but also by how and by whom it happened.

To be a Sikh is to be a learner. The Zafarnama holds great significance for Sikhs because it teaches the importance of correcting wrongdoing. Sikhi is not a pacifist religion; fighting back both spiritually and physically is a core principle. This letter is the result of Guru Gobind Singh Ji refusing to let Aurangzeb escape his heinous actions in North India. Although most resources had been used in the war, Guru Ji fought this personal war against Aurangzeb with words. The Zafarnama offers an example as to how colonized people used written moral authority to confront empire—a tactic we still see in movements led by displaced communities, whistleblowers, or activists today.

From the terrors that led to its necessity to the consequences for the Mughal emperor, each step in this tale pays homage to what it means to hold power in a struggling society. The Zafarnama teaches that one should not tolerate systemic injustice. Ultimately, the Zafarnama is not only a Sikh religious document or a poetic protest, but also a cultural artifact that illustrates how colonized peoples have challenged empires with moral authority. Researching documents such as the Zafarnama provides understanding for what can be done when history inevitably repeats itself. As a last resort, paper and ink can take the form of arms and lead to a transcendent victory.

Author Bio: Hoonur Kaur is a second-year English student at UCSB, fascinated by Sikhi and its literature. When her nose isn’t in a historical fiction, you can find her on stage pursuing a BFA degree in Theater Acting. Feel free to connect with her about all things Taylor Swift, John Green, and Princess Jasmine.