PDF Version[1]

Introduction

The formation of the Roman Empire saw the establishment of Rome’s total domination over the entirety of the Mediterranean basin. From Britain to the borders of Mesopotamia, men hailed Augustus Caesar as emperor, and the Pax Romana ushered in an unprecedented era of peace for the region. Over time, however, the cultural and administrative institutions that perpetuated the Pax Romana deteriorated, causing the Late Roman Empire to be a time of hitherto unseen catastrophe that gutted the population of entire regions. Characteristically, the middle Roman Empire is a midpoint between these two extremes, with the beginning of patterns of decline situated within a broadly still-functioning imperial system. The Severan Dynasty (AD 193-235) was the longest-lasting and most important Roman imperial dynasty of this middle period, presiding over establishing said patterns of decline that would continue to intensify over the next couple of centuries. The dynasty was original in many ways, seeing the first African emperor, Syrian emperors, and underaged emperors. At the same time, it was extremely violent, being founded by the first invasion of Italy since Julius Caesar’s civil war. Furthermore, three of its four emperors died by assassination, and the one who died peacefully did so while on a military campaign. It was thus both the product and cause of the instability associated with the time in which it ruled, making it possible for previously excluded groups to become politically active.

Under the Severan dynasty, women increasingly became involved in the empire’s politics, playing crucial roles in forming the first imperial regencies in Roman history. These changes were impactful and long-lasting, establishing precedents and trends that would affect Roman politics for centuries. Because of the violent nature of the period in which the Severans ruled, its legacies, such as increasing military control over the state and a shift towards dynastic politics, are often emphasized over the political roles of the dynasty’s women. This paper’s purpose is not to argue that one legacy is necessarily more important than another but to bring attention to a subject that I feel is often understudied and underemphasized. That is not to say that it receives no attention, however, and contemporary research on Severan women and the sources through which modernity’s information about them is derived were instrumental to forming an understanding of the subject on my part.

To draw a line between “political history” and “women’s history” for the Severan Dynasty is a misnomer and strips away deserved recognition from a group of important women whose presence has implications on the character of Ancient Rome. Understanding the gendered lens through which Severan women participated in Roman politics sheds light on the society in which they lived. Female members of the Severan dynasty played significant roles in their male relatives’ reigns, especially as underaged emperors took the throne. This played a key role in establishing the Severan dynasty’s legacy of regency politics. This was particularly exemplified by the Julias Maesa and Mamaea’s influence over Alexander Severus, who are the focus of this paper. How women interacted with the political system was affected by the informality of their positions, depending on financial wealth and connections with people invested with concrete constitutional authority. Reading between the lines of available sources is often required to discover these modes of interaction, as the presence of women was a literary motif often used by ancient authors to comment on their male relatives. Understanding the importance of Severan women to the empire’s politics is important because it affects interpretations of the empire’s cultural and institutional legacies. These legacies have effects carrying into modernity due to Rome’s influence on several Western governmental and cultural institutions.

A Brief Overview of the Severans up to Alexander

Septimius Severus seized power with his legions in AD 193 in the wake of the chaos caused by the death of Commodus’ successor, Pertinax, inflicting “the death penalty on those who had taken part in the slaying of Pertinax”[2] to portray himself as the slain emperor’s avenger and rightful successor. Despite promising to rule in a manner similar to what Pertinax had promised, granting privileges and protection to the senate, many were soon disappointed with the reality of the emperor’s character. Septimius reigned for nineteen years (AD 193-211). While his military campaigns and violent purges were significant for establishing a status quo, the majority of his rule was undertaken during a time of peace in the city of Rome. During this period and within the context of court politics, Septimius handed off many of his duties to his second-in-command, a praetorian prefect named Plautianus.

As a result of Septimius’ relative absence, his sons Geta and Caracalla indulged in the hectic environment of Rome, with Cassius Dio accusing them of having “outraged women… abused boys, they embezzled money… emulating each other in the similarity of their deeds.”[3] After Septimius died in AD 211, Geta and Caracalla took the throne as co-emperors but still “quarreled continually,”[4] and each feared the other would attempt to assassinate them. After a series of failed negotiations between the pair, a climactic decision was made to split the empire into two. Julia Domna, in response, lamenting the tearing apart of both her country and family, cried out, “Earth and sea, my children, you have found a way to divide… the continents. But your mother, how would you parcel her?”[5] Her moving display stopped the immediate eruption of hostilities, but appeals to family relations could not stop the fundamental problems that two opposed brothers desiring the emperorship posed. Of the two, Caracalla made the first move towards violence, and luring Geta into a trap using Julia Domna as bait, “killed his brother in the arms of their mother…,”[6] with Domna not only unable to stop the murder but thereafter banned from openly mourning the death of her son[7].

Caracalla, assuming sole power in AD 212, continued the bloody and violent behavior with which he took the throne. Using a literary motif owing to the Roman understanding of race and nationality, Cassius Dio accused him of possessing the “fickleness, cowardice, and recklessness of Gaul… the harshness and cruelty of Africa… and the craftiness of Syria.”[8] Motif aside, it is easy to see why he would ascribe such negative descriptions to Caracalla’s moral character. Not only did Caracalla kill Geta to assume power, blatant fratricide, but he extended the same treatment to “some twenty thousand, men and women alike” who had been in any way associated with Geta. Cassius Dio insists that the killing was so great in scale that “I never recite near the names… both guilty and guiltless alike… he mutilated Rome, by depriving it of his good men.”[9] Despite his violent securing of power, however, Caracalla’s reign lasted for four years and oversaw the formation of some of the Severan dynasties’ most important legacies, such as the Antonine Constitution in AD 212. His administration was assisted by the continued support of his mother, Julia Domna, who counseled him on how to wisely spend finances[10] and assisted him by sorting through correspondence for him while on campaign.[11]

The assassination of Caracalla in AD 217 and Julia Domna’s suicide thereafter should have resulted in the end of the Severan dynasty, as its male line was now completely exhausted and the matriarch of its maternal side dead. A surprising comeback would be made by Julia Domna’s sister Julia Maesa, who was alive and well in Syria. Using her wealth to rally soldiers around the banner of her grandson, a fourteen-year-old Syrian priest named Elagabalus (Heliogabalus), Caracalla’s usurper, Macrinus, was easily defeated in Syria in AD 218.[12] This marks a definitive change in the Severan Dynasty’s receptiveness to female involvement in politics, as Elagabalus owed his installation as emperor chiefly to his grandmother, Maesa. The “Severan” dynasty was thus now in truth that of Julia Maesa, the male Severan line having been extinguished with the death of Caracalla. Such a shift in power from the paternal to the maternal line in Roman politics in such a fashion was unprecedented, with earlier cases having been accompanied by antemortem imperial adoption.

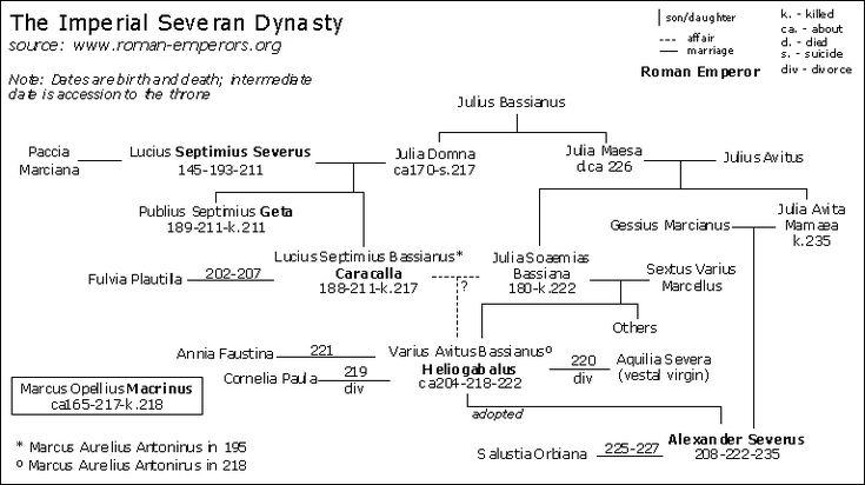

Figure 2. The Imperial Severan Dynasty. Family tree created by Gottrop Muriel.

Maesa found Elagabalus to be extremely difficult to control from her informal position once empowered, however, and the youth soon set about abusing his authority in a manner that would cause many historians to view him as one of the worst Roman emperors of all time. Immediately upon leaving Syria to assume power in Rome, Elagabalus resumed his religious rituals to his god, Elagabal, which the Romans viewed as deeply unfamiliar. Contemporaries were harshly critical of his worship, with Dio repeating the claim that he engaged in “mad activities… he went about performing, as it appeared, orgiastic service to his god.”[13] Maesa was “greatly disturbed” at his being culturally insensitive to powerful men he would need the future support of, and so she made every attempt to “persuade the youth to wear Roman dress,” [14] likely a literary motif implying that she urged him to act more outwardly Roman. Elagabalus was under no obligation as emperor to heed her warnings, however, and with what Herodian described as “contempt,” he continued to act as he saw fit,[15] even having “threatened his grandmother when she opposed him”[16] in his “marriage” (Dio himself used scare quotes) to an enslaved man named Hierocles in which Elagabalus played what Romans would have considered a female role.

In Roman society, this behavior would have been viewed as inordinately vile. Unfortunately, for Elagabalus, it could not have been written off as unfortunate personal indulgences in an otherwise successful administration. His marriage to Hierocles was not Elagabalus’ only “non-masculine” display of behavior, and his most egregious act within Dio’s account was his request to physicians to “contrive a woman’s vagina… by means of an incision,”[17] which within a premodern society would have likely resulted in a quick infection and painful death. Although these “debaucheries” could have been factually true, they were also politically significant in contributing to a widely held perception of the young emperor as feminine that would continue to shade his character centuries after his reign. Interestingly, the critique of Elagabalus’ “femininity” is not directed towards the Julias Maesa or Soaemias; however, they are represented as moderating figures whose advice, unfortunately, was not followed. Their issue with Elagabalus likely did not lie with femininity but specifically with a male displaying such qualities. Frustrated with her lack of ability to influence Elagabalus’ actions as emperor, Maesa shifted tactics in AD 222 and opted to work behind the scenes to change who occupied the throne itself. Forcing Elagabalus to adopt his cousin Alexander as heir, she then engineered a palace coup to put her new favorite grandson, Alexander, in power.

Rome’s First Puppet Emperor: Alexander Severus

Elagabalus, who began his reign so beloved by the soldiers that they flocked from his rival Macrinus to join him, now lay dead at the feet of the Praetorians along with his mother, Soaemias. Although there had been emperors in the past detested after their deaths, Elagabalus and Soaemias were so reviled that, according to Herodian, their bodies were “mutilated” and “dragged” throughout the city of Rome before being hurled into the Tiber.[18] Owing to the sheer hatred of Elagabalus by the Roman establishment, this intra-familial power struggle is universally positively regarded by the ancient sources, with disapproving references to women’s “corrupting influence” notably absent. Seeking to avoid her past mistake of giving a child authority over the state, Herodian relates how the fourteen-year-old Alexander, in this arrangement, was merely allowed the “appearance and title of emperor,” with true power remaining in the hands of “his women:”[19] Maesa and Mamaea. Elagabalus’ reign proved that two women could not rule the empire by themselves, however, and so they diffused power to multiple aristocratic advisors in a fashion that distinguished Alexander’s reign as unique from all his predecessors, a momentary reversal of the gradual autocratic trend within Roman leadership that had intensified since the time of Augustus.

This entrusting of imperial power to a council of sixteen “dignified and temperate”[20] senators epitomizes Alexander’s lack of control over his reign, even after he came of age and ostensibly became paterfamilias of his household and state. Despite his Eastern background and culture, Alexander’s reign came to embody a style of aristocratic governance long pined for by elements of the Roman cultural elite that emperors since Commodus had failed to uphold. The Historia Augusta emphasizes how he came to embrace this style of governance, instilling military discipline[21] in his troops and getting rid of Elagabalus’ gaudy visual display by adopting simple clothing. He explicitly refused to adopt titles offered to him by the Senate, such as “the Great”[22] and “Antoninus,” both of which were culturally powerful for their potential to link Alexander to admired figures of the past. Alexander’s regents, however, and perhaps the boy himself, sought to differentiate the young emperor as a new dynastic model, implicitly promising that Severan rule going forward would be vastly different. From now on, the Severan Dynasty would be traditionally Roman in character: firmly rooted in the city of Rome itself, not constantly traveling on military campaigns, and the emperor would rely on the senate for legitimacy rather than just his soldiers.

However, the heaping of praise upon the emperor in the wake of Elagabalus can make it difficult to ascertain where Mamaea and Maesa fit into this power arrangement. Although all agree that both remained relevant after Alexander took power, Maesa died early in Alexander’s reign. Furthermore, the sources differ in their characterization of Mamaea, with Herodian portraying her as a corrupt and dominating figure responsible for her son’s downfall. At the same time, Historia Augusta credits her with providing Alexander with stable influences and sage advice. Analysis of courtly intrigue such as that between Julia Domna, Caracalla, and Plautianus is not a viable mode of analysis, as the mechanics of decision-making are not described in any of the sources besides Herodian stating “nothing was said or done unless these men had first… given unanimous approval”[23] when discussing the sixteen man senatorial council. More concrete statements about Maesa and Mamaea’s role in Alexander Severus’ reign can nevertheless be made, however, if one is willing to read between the lines of literary sources and do interpretive work, as well as considering representations of the administration on material evidence such as coinage. The ruling style of Alexander Severus provides further support for the Severan Dynasty’s continuing acceptance of an increased female role in politics, with the development of regency protocols for underaged emperors being something new that would drastically affect the character of later Roman dynasties. Furthermore, while Roman politics had a dynastic and personal nature in which women could wield more power than often popularly portrayed, the intersection of Alexander’s reign with traditionally masculine institutions such as the Senate demonstrates the limitations of this mode of analysis. Disagreements between Herodian and the Historia Augusta on what precisely this institutional intersection looked like established as a Severan legacy the precedent of female political roles being highly flexible, dependent on resources at the woman’s disposal and the character and abilities of the emperor, particularly regarding regencies.

Severan Openness to Women in Politics: A More Equitable Arrangement

According to Herodian, the sixteen-man senatorial council put together by the Julias Mamaea and Maesa was designed to facilitate a more “moderate and equitable administration,”[24] an open-ended statement that leaves important questions unanswered. If moderateness was directed towards Alexander, this would refer to the surrounding of the young emperor with tutors who would impress upon him governance more acceptable to Roman citizens and institutions. It would make sense for them to construct a ruling apparatus in which his power was restricted to prevent a repeat of youthful obstinacy corrupting the public’s perception of the entire administration as had happened under Elagabalus. If this was Maesa and Mamaea’s goal, they succeeded, with Alexander being near the opposite of Elagabalus in his public behavior.

It is also possible, however, for Herodian’s description of Alexander’s reign as “moderate and equitable” to refer to a more general investiture of Roman governmental authority to institutions outside of the emperor himself. While this may appear drastic at first, the position of “emperor” had always been a legal grey area within Roman high society, and different emperors relied on the Senate for political justification for power to various degrees. It would not be unusual for an emperor to involve the Senate more explicitly in his administration, especially considering that the Senate and Equestrians had always been important to emperors because of their financial resources and political connections. Support for this interpretation comes from Herodian’s characterization of the sixteen-man council as having total control over the emperor’s political actions, with nothing being “said or done unless these men had first considered the matter and given unanimous approval.”[25] Changes were also made in administrative staffing outside of the palace, with Herodian recounting how “unqualified men whom Heliogabalus had promoted…” were replaced both by those deemed “competent lawyers and skillful orators…”[26] and “men who were skilled in the arts of war.”[27].

Part of Maesa and Mamaea’s encouragement of a more moderate government was a careful curtailing of Alexander’s education, helping form him into a more statesmanlike figure who would not chafe against the restrictions he had been placed under. They wanted Alexander to become a successful emperor to propagate the dynastic line, further justifying Maesa and Mamaea’s political involvement and ensuring Mamaea’s long-term safety in Rome. Additionally, they did not want Alexander to have full rein over the state until he reached an age when he was mature enough to do so, with Elagabalus being a particularly vivid cautionary tale of what could happen if a child was given power. The broadening of the imperial power structure to include senators who had previously been excluded did not necessarily decrease these women’s own power as compared to what they wielded over Elagabalus, which was zero, but it did mean that Alexander wouldn’t be able to single-handedly sideline them if he wanted to take a radically different approach to governance.

Maesa and Mamaea’s positions as regents were intentionally made publicly known. One example of this was in the Senate’s conferment of “imperial honors” upon Maesa after her death, recognizing her as a deity.[28] The deification of imperial family members had gradually increased in frequency over the years. However, becoming a god was still among the highest honors the Senate could posthumously bestow on a figure, so it was far from a formality. Maesa being just one advisor among many would have likely precluded her from the publicity needed for deification to be conferred on her, with recognition by either the public or influential political figures in Rome being necessary to officially carry out the process. Mamaea’s public importance in Alexander’s reign is also present in the narrative histories, albeit often through stories representing her as a malicious matriarch chiefly responsible for her son’s downfall. In Herodian’s biography, for example, despite Alexander having “blamed his mother for her excessive love of money” when Mamaea moved vast sums of money meant for bribing Praetorians into her personal control, he was unable to take concrete action to stop her.[29] She was also supposedly responsible for the removal of allies of Alexander who threatened her grip over her son, most notably his wife Sallustia Orbiana and her father, the praetorian prefect. The rank

Another example of Maesa and Mamaea’s publicly known roles is found in the distribution of coinage featuring the two. One example of such coinage is this Orichalcum sestertius (an ancient Roman coin made of a gold-copper alloy) of Alexander Severus currently displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[30] The front depicts a draped bust of Mamaea, while the back displays the goddess Venus holding a statuette and scepter.

Figure 6 (left; front). Orichalcum Sestertius of Alexander Severus: Roman: Late Imperial, Severan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 7 (right; rear). Orichalcum Sestertius of Alexander Severus: Roman: Late Imperial, Severan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The religious associations of the goddess Venus with Roman imperial power are well known, and she was commonly depicted on coinage featuring imperial women. The diadem or wreath (it is not specified on the coin’s plaque) worn by Mamaea is also something that wives of emperors had commonly been depicted with, dating back to Livia, Augustus’ wife.[31] However, the continuity of Mamaea’s public depictions of previous imperial women is important for understanding their role in Alexander’s reign. If Alexander’s regime could deliver a return to Antonine normalcy, neither the senatorial class nor the plebeians cared if his female relatives acted as regents, looking past cultural norms for the sake of stability. Imagery emphasizing continuities with previous imperial women was thus strategic in its own fashion, helping characterize Maesa and Mamaea’s powerful positions as regents as part of a gradual evolution of the imperial title instead of sudden usurpation.

The Personal Nature of Roman Politics: Maesa and Mamaea’s Fuzzy Roles

One might be confused as to why, if Maesa and Mamaea wished to remain influential in Alexander’s reign, they essentially gave control of the state away to sixteen senators. Maesa and Mamaea’s establishment of a regency council does not conflict with the two women holding power; however, it enhanced it, demonstrating how Roman women’s power was highly dependent on the personal relationships and assets of the women themselves. The two, although particularly Maesa, had just experienced under Elagabalus what happened when a teenager with only his female relatives to keep him in check was given unlimited power over the state. For Maesa and Mamaea to attempt to do so again by themselves was risky. Although all Roman politics possessed a personal aspect to it, this was particularly the case for women, whose lack of constitutional investment meant their ability to influence the emperor was limited by his willingness to listen. Alexander may have been of a milder temperament when he was a youth. Still, throughout his teenage years and early adulthood, it was quite possible that influences around him would turn the boy’s character more ambitious and obstinate, making it harder for Maesa and Mamaea to influence him. By bringing in the Senate, a powerful and respected institution even under the emperors, Alexander’s hands would now be institutionally tied by people he could not afford to defy. It is also likely that the position of the Severan dynasty was weak after Elagabalus’ downfall, meaning that forming the regency council could have been a necessity and not altruistic in nature.

The establishment of a regency council, which meant that control over all imperial actions was given over to the unanimous consent of sixteen senators, did not result in any concrete changes to Maesa and Mamaea’s situation. Had they not been included in government, their influence still would have been limited, albeit by Alexander alone. By including the senators, they may have increased the number of people they needed to convince to do anything, but they also gave themselves institutional support for any legitimately good actions they would have advised Alexander to take. Since Alexander was the last male claimant of the Severan dynasty eligible to wear the purple, the two women’s interests were tied to his well-being. Furthermore, the entrustment of “political matters and public affairs to… competent lawyers and skillful orators”[32] describes a wide-scale administrative reshuffling of those put into office by Elagabalus and perhaps Caracalla before him. This effort would have helped Maesa and Mamaea, but they did not have the power to do this themselves. The Senate and the equestrians below them were the important officials in the empire responsible for overseeing the administration, and the emperor’s closest confidants would have only been able to do so much without them. By including them in the empire’s power structure, especially with the option to later remove them once Alexander reached adulthood, Mamaea and Maesa actually furthered their own control.

Furthermore, while the council had control over actions taken by Alexander in his official capacity as emperor, Mamaea retained a “close guard”[33] over the palace. The imperial palace was the seat of the Roman government from which the emperor drafted orders and issued commands to his subjects. To control the palace would be essentially controlling the emperor, especially given Alexander’s age. Mamaea’s control was described by Herodian as being extended to Alexander, too, and not just in the manner that she could control guards and cooks to keep him safe. Herodian describes Mamaea as having “tried to govern and control him,” isolating him from “flatterers” to prevent him from being “corrupted,” similar to Caracalla and Geta[34]. Furthermore, she “induced him to serve as judge in the courts continually,” ensuring he would have “no opportunity to indulge.”[35] While the regency council may have had a powerful role in Alexander’s administration, their influence stopped where the imperial household began. Mamaea and Maesa held the role normally held by a paterfamilias here by the absence of living male Severans, including control over the emperors’ daily activity and education. This role was further strengthened when Maesa died, allowing Mamaea to act as she saw fit without consulting anyone else.

This control over Alexander by Mamaea is not corroborated by all narrative accounts of his rule; however, the Historia Augusta and Herodian disagree. This is particularly true regarding Alexander’s marriage to Sallustia Barbia Orbiana[36], a noblewoman handpicked[37] by Mamaea. Because the Historia Augusta hardly describes Orbiana at all, I am given no choice but to take Herodian’s depiction of events as at least partially authoritative, which definitively changes interpretations of Mamaea’s role in Alexander’s reign. According to Herodian, despite Alexander getting along well with his wife and father-in-law, Mamaea’s “egotistic desire to be sole empress”[38] made her increasingly “arrogant” and mistreat the girl. This stemmed from her power being rooted in the honorific title of Augusta, which Orbiana also would have possessed. Its power was thus primarily defined by Alexander’s willingness to acknowledge its importance, with two Augustas outranking each other only insofar as others recognized one as more important. Mamaea, seeing her role as gradually being diminished by this intruder into the household, ordered Orbiana’s father, an aristocrat, to be killed and the woman herself to be driven “from the palace into exile.”[39]Herodian blames Alexander’s inaction here as being a result of being “dominated by his mother…,”[40] something that Mamaea was likely only able to do because of Alexander’s youth upon assuming the throne. Roman society usually gave the paterfamilias total control over his female relatives, explaining why previous imperial mothers had lacked such control over their sons. Alexander would have had to consciously revoke Mamaea’s power upon reaching adulthood, however, which he could have been unwilling or unable to do for several reasons. Thus, Mamaea retained an outsized role in Alexander’s administration for his entire reign that she possessed by her familial relationship with the emperor.

Another example of Roman politics possessing a personal nature in which women operated can be found in Alexander’s failure to adapt when forced to embark on a campaign to defend the empire’s borders from barbarian incursions. Alexander’s reign was particularly well-suited for the city of Rome, including the Senate in decision-making and setting aside large sums of money to “gratify”[41] the Praetorians. The Senate and the Praetorians were two of the most important interest groups in the empire that an emperor had to satisfy if one was going to be ruling from Rome itself. However, the army was another important interest group, and Alexander’s mostly peaceful reign had left them ostracized from their previously paramount place in Roman political society. Alexander knew this, and Herodian reported that he was “weeping and repeatedly looking back at the city”[42] as he left to respond to a Persian invasion of the east, something completely contrary to his inclinations. Alexander had been raised by his mother to leave hard decisions to others, whether it be the regency council or herself, so to have to take up the mantle of a warrior and travel far from home must have been a terrifying concept for the youth.

That unfamiliarity with military conflict would plague Alexander’s eastern campaign, which was immediately complicated by the soldiers attempting to proclaim a man named Taurinus[43] the new emperor. The Historia Augusta represents Alexander as able to bravely face down the mutineers and those refusing to obey codes of military discipline in Antioch,[44] but it was nevertheless a serious impediment to the campaign that took precious time to address. The Historia Augusta and Herodian significantly disagree on how Alexander fared in the Persian campaign, with Herodian representing it as a stalemate in which Alexander was unwilling to personally fight[45] and the Historia Augusta describing the campaign as so successful that Alexander was rewarded as a triumph on his return to Rome.[46] Of the two accounts, Herodian’s appears more reliable, since Alexander’s lack of wrongdoing in the Historia Augusta causes his assassination to feel bizarrely out of place compared to Herodian’s account, which results from gradual dissatisfaction among the soldiers. According to Herodian’s account, after an effective stalemate against the Persians following failed diplomatic negotiations and the destruction of an entire army, Alexander was forced to respond to a massive Germanic invasion that made it “absolutely necessary that he and his entire army come”.[47] Once again, although he “loathed the idea, Alexander glumly announced his departure”[48] and actually crossed the Rhine into Germania.

While in Germania, Alexander was literally slain while “clinging to his mother”[49] and crying over his fate. Alexander’s competency as emperor was undergirded by questions of how influential his mother was, with a woman holding political power over the empire anathema to at least some parts of the military. Mamaea’s role heavy involvement in Alexander’s reign may have soothed the Senate in Rome, who viewed her as a beacon of rationality following Elagabalus, but the soldiery wanted a traditionally masculine emperor who was competent on the field of battle. More importantly, Alexander’s being isolated to the courts and civilly-inclined tutors during his upbringing meant it would have been difficult for him to navigate the military culture familiar to Severus and Caracalla, who heavily relied on the army as supporters of their dynasty. What worked in Rome did not work on the frontier, where the Senate and Praetorian Guard were replaced as interest groups able to affect the emperor’s safety with the army alone. A woman’s role in Roman politics was thus demonstrated to be highly dependent on their geographic location, which affected acceptable manners in which they could rule.

Reading Against the Grain of the Sources: Disagreements Between the Historia Augusta and Herodian

While narrative histories, including the Julias Domna, Maesa, and Soaemias, all contain broadly similar depictions of historical events, the Historia Augusta and Herodian’s views on Alexander Severus and the Julias Maesa and Mamaea wildly disagree with each other. The Historia Augusta presents Alexander as being highly competent at the emperorship almost immediately, with his first action having been to “forbade men to call him Lord”[50] and reverting the emperor’s garments from Elagabalus’ jeweled finery to a “plain white robe.”[51] According to the Historia Augusta, Alexander had been “nurtured from his earliest boyhood in all excellent arts, civil and military”[52] by his mother, and that nurturing combined with a naturally amenable character carried over into everything he did. Julia Maesa was an intelligent woman who advised her son well with “righteous” counsel, unfairly becoming the target of a propaganda campaign through no fault of her own. In Herodian’s view, however, Mamaea’s efforts to educate and guide Alexander derived from a desire to “govern and control”[53] the youth. Her embezzlement of money[54] and murder of Alexander’s wife went unpunished, as her control of the imperial household was too great for Alexander to offer any significant challenge. His ability to properly carry out administrative duties was neutered by the sixteen-man council put together by Maesa and Mamaea, and his duties as emperor were mostly limited to judging in the courts.[55] These two views of Mamaea, one a dutiful advisor and the other a contriving matriarch, are incompatible. To understand why they exist, a larger narrative view of the purposes of both sources needs to be considered.

The Historia Augusta is a biographical-style history of the Roman Empire using emperors as the subjects along with their vitae,[56] or heirs. Although the work had multiple different authors, the chapter on Alexander Severus is typically attributed to Aelius Lampridius, who wrote upon Emperor Constantine’s direct request.[57] The thematic construction of chapters took inspiration from the Lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius, which the Loeb introduction describes as “not biographies in the modern sense… but merely collections of material arranged according to certain definite categories.”[58] These definite categories often followed the course of literary themes, and speeches documented in the work are often fictitious and made to fit the theme owing to the influence of Thucydides’ Greek histories. Later authors sometimes added these fictitious elements, and most commonly appear when episodes from an emperor’s personal life are described. Because so much of Alexander’s reign took place within the confines of the imperial palace, however, this means that much of Alexander’s chapter isn’t rooted in actual historical fact. This is especially true for chapters twenty-nine to fifty-two of his biography, titled in my LacusCurtius translation as “private life and character.” Stories like his early morning worship routine,[59] his giving away of all but the simplest garments,[60] and his shunning of his Syrian ancestry in conversation,[61] are all completely unique to the Historia Augusta, uncorroborated elsewhere.

However, the questionability of the historical accuracy of specific events does not make the Historia Augusta completely useless as a source. First, historians like Edward Gibbon[62] took its contents as historically accurate, so if one is wading into historiographical debates, it can be useful for understanding how other historians formed their arguments. Second, the date of composition under Constantine helps indicate how later Romans (albeit from the limited perspective of court officials) thought about their predecessors. Alexander’s portrayal as an extremely competent emperor contrasts with the soldier-emperors who would rise after his reign, many of whom reigned for a year or less. The empire was thrust into a period of instability that culminated in the Crisis of the Third Century. Consequently, Alexander would look extremely capable by comparison as the last bastion of stability before a decline. Additionally, the influence of women in imperial affairs increased over time as boy emperors became more common, and piety became a legitimate reason for women to be involved in politics. This was particularly the case with Constantine, whose mother, St. Helena, was an important part of the empire’s conversion to Christianity, an important legacy of his reign. For Lampridius to represent a mother as providing wise counsel to her son would not be anathema, since it is detached from the Severan era context of a woman’s involvement being the result of her male relative’s incapableness. Alexander was wise despite his age, so taking his mother’s advice was more the result of filial piety and the good quality of the advice than it was being forced into it.

In contrast, the History of the Roman Empire From the Death of Marcus Aurelius to the Accession of Gordian III, written by the civil servant Herodian, possesses an entirely different style. The chronological period covered by the book was chosen because Herodian identified the death of Marcus Aurelius as the end of an age[63] for Rome, and its straightforward biographical structure reflects that.[64] Traditional rules of Roman politics had broken down, with powerful generals able to seize the purple at will and the senatorial class at constant risk of being purged by the new “emperor of the year.” Although never explicitly described, contemporary readers would have identified themes like the emperors’ presence being increasingly required to fight off invasions on the frontiers as a symptom of the clearly identifiable decline[65] Herodian was commenting on. Rather than by virtue, nostalgically embodied in the memory of Marcus Aurelius, emperors like Septimius Severus were able to seize power merely by commanding an army at the right place during the right time. [66]

Much of Elagabalus and Alexander’s biographical accounts, therefore, while unique to their personal characters and the role of their mothers and grandmother, are merely part of larger trends described by Herodian. The most important of these trends is the inability of any one regime to satisfy all constituent elements of Roman society, with divisions like the army vs. the Senate and the western vs. eastern parts of the empire clear throughout.[67] In relation to Alexander, the divide between the army and the Senate is the most important to understand. Septimius Severus’s setting of a precedent whereby generals could march into Italy with their troops and seize power could not later be undone. It is only narratively fitting that the Severan dynasty should end by military force, the same tactic they used to secure their initial rise under Septimius. While Herodian wrote his histories closer to the date that the Severans reigned as compared to the Historia Augusta, because of this overarching structure, specific events of his also need to be interpreted as potentially symbolic. Coins and statues are also useful, helping historians understand the past beyond what textual problems would otherwise limit them to.

The differences between these two sources are useful for understanding my methodology, whereby I attempt to understand the concrete roles that the Julias played in their male relatives’ reigns. I will never be able to say with certainty, for example, whether Alexander’s continuing use of the senatorial class in his reign was a result of his mother’s influence or a personal decision to rule in a style acceptable to interest groups relevant to his safety. By combining commonalities between the accounts, however, I can say that Julia Mamaea was an important power player throughout her son’s entire reign, giving him advice and accompanying him on military campaigns across the empire. Furthermore, just because the information within the narrative sources is biased does not mean that they are false, and the general gist of a description can be true without every individual detail needing to be corroborated. The two sources’ descriptions of the same events need to be examined side-by-side, then, with the reasons behind their respective portrayals then being made clear.

When the accounts are closely read, it is clear that Herodian’s broad characterizations of Alexander Severus and Julia Mamaea are more reliable. In Herodian’s account, the soldiers become tired of Alexander’s repeated attempts to make unfavorable peace treaties so that he might return to the comfort of Rome, as well as generally disliking him because of the perception of him being a “mother’s boy.”[68] These assertions are not immune from being narrative in nature, with the second part possibly being an allusion to general discontent over the softness of his rule in the army’s eyes. The Historia Augusta, however, gives no concrete justification for why Alexander Severus was assassinated outside of vague allusions to a plot carried out by Germanic guardsmen. If I am to attempt to construct a picture of the past, I would rather try to wade through a knowingly biased interpretation from one source than one that offers no interpretation at all.

Operating off this principle, I arrived at the vague generalities about Julia Mamaea’s role in Alexander’s administration described in the first part of this section. It is clear that she played an important role alongside Julia Maesa during Alexander’s early reign, and both sources describe the Senate as playing a more active role than they had under Septimius or Caracalla. Furthermore, that role continued even after the death of Julia Maesa, which establishes that Mamaea could navigate the political scene more effectively than Soaemias. For her to be a background character in this while her teenage son ruled alone does not seem like the likeliest course of events, and while characterized differently, both sources confirm that she had an influential role in palace affairs and how the emperor spent his time. Even the Historia Augusta, which attempts to establish a positive overall image of Julia Mamaea, concedes that the soldiers who overthrew Alexander in favor of Maximinus Thrax used her role in Alexander’s reign to portray the emperor as having been corrupted and emasculated. Although broad, the assertions that can be made about her role in Roman history are important for understanding both Alexander Severus as an emperor and the ability of women to interact with the political system more generally.

Conclusion

From the very first moment the mantle of emperor was thrust on him by his mother and grandmother, Alexander Severus was limited in how much he could exercise his power. These limitations directly responded to the reign of Elagabalus before him, whose excesses were likely interpreted as embodying the risks that allowing absolute power to a teenager could produce. Whether by the imposition of a sixteen-man regency council or by deferring to them in matters of administration, the Senate was brought in to help administrate and educate Alexander. Julia Maesa died soon after the status quo was established, and Mamaea took up the position of regent for herself. From here, she maintained total control over the imperial household, pushing out rival aristocrats who threatened her influence over her son and hand-picking advisors who would train him in certain ways of thought. This strong regency eventually worked against Alexander’s public image, with the army citing his being dominated by his mother as a reason why he was unfit to lead, assassinating him while on a campaign.

The primary reason why Maesa and Mamaea were able to do this was Alexander’s age upon assuming the throne. Since the Severan dynasty lacked a single male claimant other than Alexander, they could take the position within the imperial household a paterfamilias traditionally would have occupied. To wield power beyond the palace, however, they needed the assistance of institutions primarily comprised of men, namely the Senate and Praetorians. While this made their rule remarkably stable within the city of Rome itself, a perception held by some of the regime’s domination by females combined with Alexander’s age made extending their influence beyond Rome itself difficult. The story of a revival of senatorial authority, did not play well with the self-interested army. Their role was only able to be filled by Maesa and Mamaea because of their familial relationship with Alexander, with other aristocratic families presumably possessing just as much wealth, never able to displace the two.

When trying to separate fact and fiction about Maesa and Mamaea’s roles in Alexander’s administration, historians must remember the intended purpose of the books they are using. The Historia Augusta was written around biographies of individual emperors and their heirs, with a moral theme usually commented on within personal anecdotes about the emperor’s personality and private life. Herodian’s history, in contrast, has one overarching theme of decline since the death of Marcus Aurelius, and one of the biggest aspects is the depravity of the emperors.. The inherent meaning that a woman’s presence would have within Roman politics must, therefore, be balanced with the very real assistance Alexander, a teenager, would have required if he was to rule the Roman Empire. The common appearance of details concerning Mamaea functioning as a regent and manager of the imperial household suggests that she played a very significant and influential role in Alexander’s reign. The positive representation of her nearly a century later in the Historia Augusta helps establish that Severan women’s roles in their male relatives’ reigns helped establish a long-term trend of more female involvement in Roman politics. This was especially the case as the empire’s politics became more dynastic, increasing the power of family members regardless of gender as youths inheriting the throne justified the role of regent. This trend was established under the reign of the Severans, cementing their women as playing a pivotal role in the dynasty’s long-term impact on the empire.

[1] Cole Grissom graduated from UC Santa Barbara as part of the Class of 2024 and is currently a 1L at the University of Virginia School of Law. While at UC Santa Barbara, Cole’s historical research focused on the middle and late Roman Empire.

[2] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIV, 163.

[3] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXVII, 253.

[4] Herodian, The Reign of Caracalla (211-217). Translated by Edward C. Echols. Livius, 2022, 4.1.1.

[5] Herodian, The Reign of Caracalla (211-217), 4.3.8.

[6] Herodian, The Reign of Caracalla (211-217), 4.4.3.

[7] Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXXVIII, trans. Bill Thayer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 231.

[8] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXVIII, 292.

[9] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXVIII, 291.

[10] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXVIII, 301.

[11] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIX, 347.

[12] Herodian, The Reign of Elagabalus (218-222), 5.3.11.

[13] Herodian, The Reign of Elagabalus (218-222), 5.5.4.

[14] Herodian, The Reign of Elagabalus (218-222), 5.5.6.

[15] Herodian, The Reign of Elagabalus (218-222), 5.5.6.

[16] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXX, 467.

[17] Dio, Epitome of Book LXXIX, 471.

[18] Herodian, Elagabalus (218-222). Translated by Edward C. Echols. Livius, 2022, 5.8.9.

[19] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.1.

[20] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.2.

[21] The Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, trans. David Magie (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 287.

[22] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 188.

[23] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.2.

[24] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.1.

[25] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.2.

[26] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.3.

[27] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.4.

[28] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.3.

[29] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.8.

[30] “Orichalcum Sestertius of Alexander Severus: Roman: Late Imperial, Severan,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed March 6, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248064l Liana Miate, “Orichalcum,” World History Encyclopedia, Last modified December 07, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/Orichalcum.

[31] The Roman Numismatic Gallery, “The Emperors’ Wives and Families,” Accessed March 6, 2023, http://www.romancoins.into/Kaiserinnen.html.

[32] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.4.

[33] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.5.

[34] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.5.

[35] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.6

[36] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 59.

[37] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.9.

[38] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.9.

[39] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.10.

[40] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.10.

[41] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.9.

[42] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.3.1

[43] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.4.7.

[44] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 289.

[45] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.5.9.

[46] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 293.

[47] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.7.3.

[48] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.7.5.

[49] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.9.6.

[50] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 185.

[51] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 186.

[52] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 184.

[53] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.5.

[54] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.8.

[55] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.1.6.

[56] Historia Augusta, Introduction, xv.

[57] Historia Augusta, Introduction, iv.

[58] Historia Augusta, Introduction, xvi.

[59] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 237.

[60] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 259.

[61] Historia Augusta, Severus Alexander, 268.

[62] Historia Augusta, Introduction, xxxi.

[63] Echols, “Introduction”, 1.

[64] Adam Kemezis, Greek Narratives of the Roman Empire under the Severans (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 21.

[65] Kemezis, Greek Narratives of the Roman Empire under the Severans, 240.

[66] Kemezis, Greek Narratives of the Roman Empire under the Severans, 280.

[67] Kemezis, Greek Narratives of the Roman Empire under the Severans, 83.

[68] Herodian, The Reign of Severus Alexander (222-235), 6.8.3.