In 210 BCE Ying Zheng, the First Emperor of Qin, climbed Mount Kuaiji in the company of his officials. They left a text on the stone at the top of the mountain that praised Qin and its leader’s great accomplishment in their newborn conquest and rule on this land that would—centuries later—be known as “China.” However, this emperor, who hoped “his constant governance would know no end,”[2] may not have imagined that his own life would be ending soon. Enraged commoners ultimately overthrew his imagined eternal empire just a few years later. Centuries have passed since the rise and fall of the Qin Dynasty, yet the narratives and prominent personalities of this era have not been consigned to the annals of history. Besides being material for the political treatises written in later dynasties, the stories and figures of Qin have also become the focus of dozens of historical strategy games in modern times. Not only did Chinese gaming companies gain inspiration from Qin’s story, but in Japan and the U.S., some games have either made Ying Zheng a playable character or made him the in-game leader of Chinese civilization. When playing the game as an in-game state leader, players can be/can live alongside Qin figures using their unique traits and abilities, assisting them in either conquering or winning over their opponents through the process of “agriculture and war.” Players are also practicing the “oneness”—a core of Qin’s Legalism that strives to implement the ruler’s will throughout the nation—for being the ultimate despotic leaders of their forces. This paper explains how some modern turn-based strategy games represent the Qin Dynasty and how these representations draw inspiration from other historical conceptualizations. Upon conducting a meticulous examination of both games, coupled with extensive research into historical records and gaming mechanics, we will discern how the distinctive attributes drawn from historical accounts not only render Ying Zheng and his officials invaluable allies for players striving to achieve victory but also set them apart from their adversaries. Simultaneously, the strategic game’s intricate mechanics and governance perspective allow players to govern their forces indefinitely, mirroring Ying Zheng’s aspirations for his rule, all while minimizing internal challenges.

Modern historical electronic games can be seen as both interpretations and recreations of history. With the growing game industry continuing in the twenty-first century, electronic games have gradually become one of the school-age teenagers’ great playmates. Among the games, certain historical electronic games have entered some educators’ sight for having the potential to “…teach about the past.” For instance, Krijn Boom from Leiden University noticed that historical video games are a “manifestation of experiential learning history,” as their “interactive nature” can bring “immersive experience” with “a deeper level of personal and historical learning.”[3] While recognizing electronic games as a vector of historical education, educators are also aware of the games’ “representation “of history, which should better not be trusted as “unbiased views of history.”[4] Similarly, another researcher from Leiden University proposed that electronic games are “first and foremost entertainment and artistic products” that need to be fun instead of “accurate reproductions of the past. The various interpretations of the Qin Empire in modern electronic games somewhat echo Anthony Barbieri’s research about the First Emperor on screen, where he critically analyzed the “reinterpretation and mythmaking” surrounding the Qin Empire on modern cinema and television.[5] In an era in which electronic games seem to have an increasing influence on the younger generation’s worldview, the researchers may have more resources and motivation to investigate how historical electronic games interpret and recreate history. Thus, I chose two of the most famous historical electronic game series with Qin figures, based on game forum discussions and e-game store downloads, as my research subjects.

In the following paragraphs, some readers may notice that the passage heavily depends on secondary sources like Sima Qian’s The Records of the Grand Historian as a major source of comparing the Qin figures in the game and themselves “in history.” At the same time, some historians had already reported the mixture of historical facts, popular legends, and Sima Qian’s personal bias/ intentions in his work, The Records of the Grand Historian. Barbieri suggested that some events in the First Emperor’s life were “fabricated entirely” by Sima Qian to better match Sima Qian’s subject of indirect exhortation: Emperor Wu of Han.[6] Other historians doubted that Sima Qian, with his “common eastern misperception” against Qin, assigned the state with “pejorative remarks” of barbarism.[7] More vehement criticism for Sima Qian’s creation of “a literary universe that doubled and replaced the real world of events” instead of making “true records” of the past also exists.[8] Setting aside the doubt about the credibility of some secondary sources, even some of Qin’s stone inscriptions as primary sources were reexamined by critical eyes. Martin Kern, in his work “Announcements from the Mountains,” suggests that the Qin inscription can be seen as a “sacralized distillate of history” that is both “radically abbreviated” and “profoundly ideological.” [9] This paper is not trying to inspect the gap between the Qin empire in games and the “real” history but comparing the characteristics of the empire in modern electronic games with its attributes in some of the most famous and time-honored works. Instead of diving into the sea of ancient documents to approach Qin’s actual image, the paper focuses on its application in modern historical strategy games, along with the game designers’ potential goals in constructing their versions of Qin and how the perspectives within these two games contribute to the empire’s presentation.

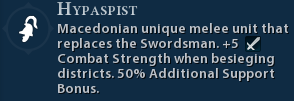

To begin our discussion, we will turn to a Japanese game published in 2006: the Romance of Three Kingdoms XI.[10] Romance focuses on the political and military struggle during the Chinese Three-Kingdoms period (184 CE – 280 CE). Playing as a warlord polity in the chaotic Three-Kingdoms period, the players must strengthen their polities by developing their cities, recruiting officers with varied abilities in domestic or military affairs, and expanding their armies by recruiting soldiers and weapons production. Though the players are free to try different playing styles, the game only has one official condition for victory: the player’s polity must possess all the cities on the map. In other words, they must unify China. Besides having the victory condition which echoes Qin’s conquering process, the game also employs four Qin historical figures: Ying Zheng, Li Si, Meng Tian, and Wang Jian, titled as “ancient officers” who could be deployed in this stage of heroes, to compete with them for a unified China. Also, as military conquest is the only decisive means to unify China, other polity affairs, like domestic development and diplomacy, can be seen as auxiliary means that contribute to the benefits of military expansion. This militarism also echoes Shang Yang’s “Agriculture and War” chapter in the Book of Lord Shang. This legalist work supposedly organizes all people to engage in battle or support the army. In general, though the Romance of Three Kingdom XI seems unrelated to the Qin time period, players can still use Ying Zheng and his officers through a gaming mechanic that fits well with parts of Qin’s ideology to achieve the goal that Qin accomplished. Later, we are going to see the four Qin officers in the game to investigate their in-game data and traits, and compare this with the historical record, and see what they can contribute to the player’s polity.

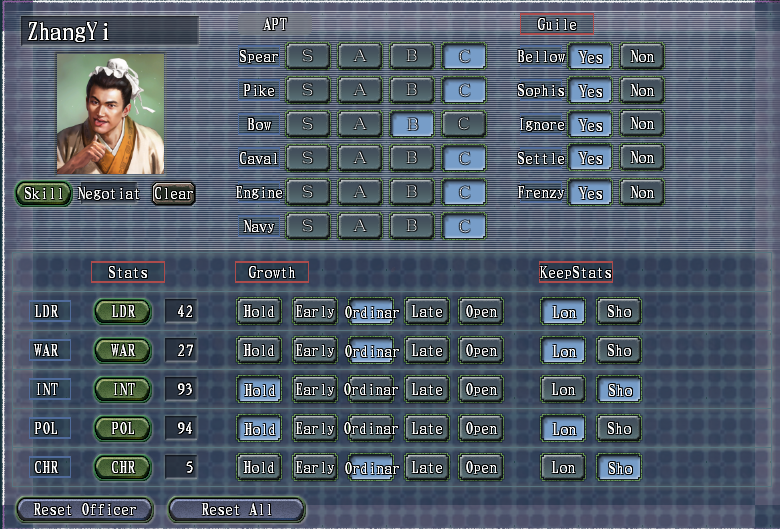

Maybe we need a brief introduction to the character interface before introducing the Qin figure’s in-game performance. As Appendix A, figure 1 shows the character’s name and image and the individual trait on the top left. At the lower left, we can see the character’s stats on Military Leadership, Martial Arts, Intelligence, Political Ability, and Charisma. The character traits and their stats are the two major parts of character design that draw from their historical reputation. In contrast, other unmentioned parts might be created to enhance the gameplay. As a result, we will focus on the Qin characters’ stats and traits.

Having familiarized ourselves with the character interface, let’s examine how Ying Zheng’s in-game data aligns with his historical character (see Appendix A, Figure 1). Ying Zheng enjoys top political ability and intelligence but has mediocre warfare abilities in areas like Military leadership and Martial Arts. From Ying Zheng’s in-game stats, it is easy to see his role as a civil official suitable for domestic development but with limited capability in war. In the Record of Great Historian, Sima Qian did not paint too many positive portraits of Ying Zheng’s military leadership or martial arts. Ying Zheng seems weak in martial arts abilities, as he was in “panic-stricken confusion” during Jing Ke’s assassination attempt and his “life was threatened” when he encountered bandits in 216 BCE.[11] Although he did visit his generals at the front on more than one occasion, there are no documents which mention Ying Zheng leading an army by himself. As a result, Ying Zheng failed to receive a good military stat. In contrast to his poor military stats, Ying Zheng had top stats in his Political Ability and Intelligence. His capabilities in both are documented in The Records of Grand Historian. When Lao Ai plotted a revolt with the Queen Dowager and replaced the guarding soldiers with Rong and Di tribes, Ying Zheng, who was in his early twenties, did not surrender. Instead, he ordered his loyalists to pacify Lao Ai’s revolts after “several hundred heads were cut off” and tore Lao Ai “in two by carriages” to warn those potential dissenters.[12] As the founding father of the first centralized dynasty in Chinese history, with the political ability to pacify a threatening coup d’état in his early twenties, Ying Zheng’s political ability and intelligence stats in the game are warranted. Besides Ying Zheng’s in-game stats, he also has the power of taxation. The trait halved his resident city’s gold income in a round while tripling the frequency of receiving it. Thus, Ying Zheng’s trait increased the total Gold income in his resident city by 50%. Gold in the game is the basic resource that can be transferred to other vital resources like army provisions or equipment for the soldiers. Meanwhile, most in-game actions, like conscription, equipment production, and technology research, need gold. As a result, Ying Zheng’s trait is an easy but beneficial booster that does not need excessive maintenance. The player just needs to send Ying Zheng to a city and enjoy his gold multiplier, which can bring additional resources and open up more possibilities in all spheres of action that contribute to military conquest. Besides its in-game performance, Ying Zheng’s trait also reflects a judgment from the designers on what his administration was notorious for in history. In the game, only one character possesses the Taxation trait besides Ying Zheng: the notorious tyrant Dong Zhuo. Three Kingdoms Dong Zhuo’s atrocity of burning down Luoyang, the capital of the Eastern Han, when he feared attack. By making Ying Zheng the only person who shared the same trait as Dong Zhuo, the game designers may want to create a parallel between those two persons, who committed great atrocities and generated great resentment among the people and criticism from later historians. Despite this potential parallel, Ying Zheng is still a positive figure for a player, an expert in domestic affairs like construction, with a unique trait that can bring players more choices and possibilities in their conquering process.

In Li Si’s case (See Appendix A, Figure 2), we can see how the figure’s historical blemishes had a minor effect on his in-game performance. Like his emperor, Li Si, the grand councilor of the Qin Empire and the architect of several of Ying Zheng’s policies received high stats in Intelligence and Political Abilities alongside Ying Zheng. However, Li Si’s Charisma stats were much lower and similar to those with a negative historical portrayal. In Sima Qian’s work, we can find several clues behind Li Si’s poor Charisma rating. For instance, when Li Si proclaims his purpose in serving in Qin, he does not make ambitious claims like assisting a future overlord or conquering the six states. Instead, he claims a practical reason for escaping a “mean and lowly station” with “a situation of hardship and trial,” as there is “no greater sorrow than poverty and want; no great disgrace than being mean and lowly.”[13] This claim itself is not problematic, however, in Sima Qian’s work, we see the troublesome other half of Li Si’s claim that he did not speak. When he reached his high position, he would see protecting his position as his primary task. To ensure his position after Ying Zheng’s death, Li Si finally agreed to collaborate with Zhao Gao’s plot to make a fake imperial edict. Later, as the civilians suffered from Hu Hai’s autocracy, though Li Si once tried to persuade the emperor for a softer policy, he again changed his mind and promoted severe “supervision and reprimand activities,” as he was “reluctant to lose his title and stipend.”[14] This policy proved disastrous as it made the empire have “half of all the people passing along the roads had suffered punishment, and the bodies of the dead daily piled up in the market place.”[15] As a result, Li Si, a weak-minded and two-faced profit-chaser who failed to stop Qin’s autocracy, logically received a poor Charisma rating in the game. Indeed, as an officer with low Charisma, Li Si can hardly recruit other officers for the player. Still, his trait- “Efficacy,” is another easy but helpful booster—like that Taxation trait of his emperor. The effect of this trait is to multiply equipment production by roughly two times, which, combined with Ying Zheng’s Taxation, would bring a powerful boost to a city’s equipment production. The charts below compare equipment production and the gold surplus in ten rounds in the same city under four conditions: With both Li Si and Ying Zheng; with Li Si and without Ying Zheng; with Ying Zheng and without Li Si; and without both Ying Zheng or Li Si. After comparing the conditions, we can see that the combination of Ying Zheng and Li Si can produce some gold surplus, maximizing the production efficiency of equipment allowing the player to make a more flexible strategy while enriching their military power.

| Li & Ying | Only Li | Only Ying | Other officers | |

| Equipment | 52040 | 52040 | 28240 | 23120 |

| Gold surplus | 3000 | 899 | 3958 | 536 |

Now, let’s turn our attention to the presentation of characters Wang Jian and Meng Tian, as well as the military capabilities of the Qin Dynasty in the game (refer to Appendix A, Figure 3). Though both Wang Jian and Meng Tian did not receive top stats for Warfare, they were generalists who could also participate in domestic production while being able to cope with most of the combat conditions. If we quickly glimpse Wang Jian and Meng Tian’s Military Leadership and Martial Arts stats in Figure 3, we will soon find out that their stats cannot be regarded as the “top” among their counterparts in the Three Kingdoms period. Though Wang Jian received a high rating in Military Leadership, maybe because Sima Qian’s documents his leadership of 600,000 soldiers in a successful battle that “dealt a crushing blow to the Jing army,”[16] his Martial Arts stat is low among military generals, as little personal fighting ability was mentioned by Sima Qian. He was also quite elderly during the final conquest. Meng Tian in the game received more balanced stats than Wang Jian, maybe because of his accomplishment in leading “a force of 300,000 men” and expelling the “Rong and Di barbarians,” who were considered fiercer than the Jing soldiers. His military stats are still lower than those of top generals in the Three Kingdoms period, like Lu Bu or Guan Yu.[17] However, Wang Jian and Meng Tian had high Intelligence and Political Ability stats among generals to distinguish them as well-rounded characters suited for multiple areas besides just leading their troops into battle. Sima Qian mentioned Wang Jian’s political wisdom in not giving Ying Zheng “occasion to doubt his motives” by “repeating his request for suitable farmlands” multiple times to present himself as having low ambition.[18] As a result, Wang Jian’s Intelligence and Political Ability stats exceeded 70, making him a useful figure for domestic construction. This characteristic is helpful for the player who is short on officers in the early stage of the game. Like his compatriots, Meng Tian also received comparatively decent stats for Intelligence and Political Ability for his righteous opposition to Zhao Gao’s forged order. Besides his basic stats, Meng Tian’s special ability in Construction also boosted his utility in military construction. As a general who took Ying Zheng’s order to construct the Great Wall that “began at Lintao and ran east to Liaodong, extending for a distance of over 10,000 Li,” and an imperial road that would “cut through mountains and filling in valleys for a distance of 1,800 Li,” Meng Tian in the game, is also a master in constructing military fortresses.[19] With his trait that can halve the required time for building a military facility, Meng Tian can quickly construct a series of fortifications in the opponent’s potential attacking directions. With those fortifications, the player will need to send fewer troops to repel enemy attacks while saving them for their attacks in the future. The two in-game screenshots of Appendix A, Figure 4, display Meng Tian’s in-game efficacy of military constructions. The picture on the left represents the construction done by an officer without Construction in 10 rounds, and the picture on the right represents the construction done by Meng Tian in 10 rounds. The difference in complexity between the two fortifications somehow again reminds us of Wang Jian and Meng Tian’s in-game performance. Perhaps they could not perform as the top officers on the battlefield. Still, they could participate in the preparations before going into the battle to create more comfortable conditions for the players when they encounter battles, whether voluntarily or not.

Some other Qin figures, like Bai Qi and Zhang Yi, also appear in the game. As they were not strictly contemporary with Ying Zheng’s empire, the passage will not provide similarly detailed analyzes as those done on the four figures discussed above. And, though the two figures in-game have been specialized for either combat or diplomatic scenes, they made small effects on the major play style of the Qin empire (though in a wider historical period). In Figure 4, the readers can see Bai Qi received the highest Leadership among all the generals in the game: 100, for Qin’s massive military successes achieved with an enormous army under his command. With other stats being assigned impressively as a military officer, Bai Qi can be seen as one of the top generals in combat. However, as other polities- mostly The Three Kingdoms -formed an oligarchy on the top combatants, having only one Bai Qi can hardly help the Qin in the game gain the upper hand on the battlefield. Especially when multiple troops usually participate in one battle while one general can only command one. Similarly, Zhang Yi’s outstanding personal abilities in-game are also encumbered by the game’s emphasis on military expansion. As displayed in Figure 4, the game designers assigned brilliant Intelligence, Political ability and the trait “negotiator” to Zhang Yi. In diplomatic missions to other polities, Zhang Yi’s trait can bring compulsory debates between himself and the opponents’ intellectual counselor. If Zhang Yi successfully wins a debate, the losers will execute the player’s diplomatic demand regardless of their original intention to the player’s proposal. Since the debate system in the game is similar to card games in which a character’s Intelligence determines the quality of cards, Zhang Yi’s high Intelligence provides players with better cards, which equals higher chances of winning against their opponents. However, the entire diplomatic system in the game is not designed as a major means for conquering. As soon as other non-player polities detect the threat of players’ enlarging territory, they will automatically form alliances against the player’s polity, even if the war among them still enrages in previous rounds. Meanwhile, the clash of larger powers after political annexation is unavoidable in the late game, as the diplomatic mission “Induce to capitulation” when only two polities still exist on the map would automatically fail. Thus, though having Zhang Yi can enrich players’ diplomatic choices in the earlier stages of gameplay, Zhang Yi’s later contributions are mitigated, as the in-game diplomatic system in the later stages is seemingly designed to create challenges for military conquest rather than promoting it.

Putting all six Qin officers together, we may find that their attributes in different areas echoed Shang Yang’s famous saying: “The means whereby a country is made prosperous are agriculture and war.”[20] In the game, agriculture is distorted into the “farming” process one engages in before entering battle. The process can be seen as supporting the “war” aspect. All six Qin officers can participate in this process with their advantages in the game. The gold surplus created by Ying Zheng’s abilities can be transferred to the mass equipment production boosted by Li Si’s ability or the military construction led by Meng Tian’s rapid construction ability or even be distributed to other important tasks like soldier recruitment. Zhang Yi’s diplomatic contributions can help players aggrandize their force by avoiding entanglement in undesired conflicts in the early game. Though the Qin officers as a whole are not the top fighters on the battlefield, their productivity in the “agriculture” sector allows them to overwhelm their enemies with their abundant military power. In return, this process can strengthen the player’s combat performance as the annexation of other warlords can bring more officers who are more capable in combat affairs. Thus, a positive feedback loop between agriculture and war is established, and it will keep rolling until the player captures all the cities in the Chinese territory.

While commending the individual prowess of Qin officers, it becomes evident that the game’s emphasis on Qin’s military expansion tends to diminish other facets of the empire. For instance, Qin’s heavy corvee mentioned in Meng Tian’s personal trait is incomplete, as it abstracts the empire’s labor force mobilization on both military and non-military constructions, transforming it into a personal trait that strangely relates to construction speed.The Qin Empire’s civilians, described as “weary from labor” and “unable to find rest” with insufficient clothing and food, as expressed by Jia Shan, are portrayed in the game as not even voicing their grievances.[21] People’s satisfaction with a city’s government was generalized as a city’s Public Security Number. Though maintaining a lower Public Security would negatively affect cities’ production of gold and rations, players could send officers with higher military stats to patrol the city and boost the number. Then, the civilians represented by this abstract number, who had been vocal in their discontent due to oppressive exploitations in the previous rounds, would immediately retake their pride as subjects, ready for a new round of mass recruitment. Thus, though the Qin stone inscriptions praised the empire’s ability to “adjust the laws and precedents and delineated offices and responsibilities” to “establish constant procedures,” the game presents Qin—and all other polities—as stronger or weaker war machines that value combat as the only way to survive and thrive, leading the entire state into endless wars that destroy others or destroy itself.[22]

Civilization VI

The gaming industry is continually progressing. In 2016, the game Civilization VI was published.[23] Unlike Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI, the game utilized a more complex mechanic, including factoring in population size and citizen loyalty, that can create a comparatively more complex but realistic mechanism to represent the commoners. The victory conditions for Civilization VI are more numerous than those in Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI. In Civilization VI, victory has to be achieved through full territorial control, along with a number of other preconditions. Besides the Domination Victory, players can also win the game through Science Victory, Culture Victory, or Religious Victory. Though those progress in game design, in the view of a research report on Civilization’s realism, “is not anchored in the sense of historical accuracy,” they still provide a “playful exploration through abstract representations” of the civilizations’ rise and fall.[24]

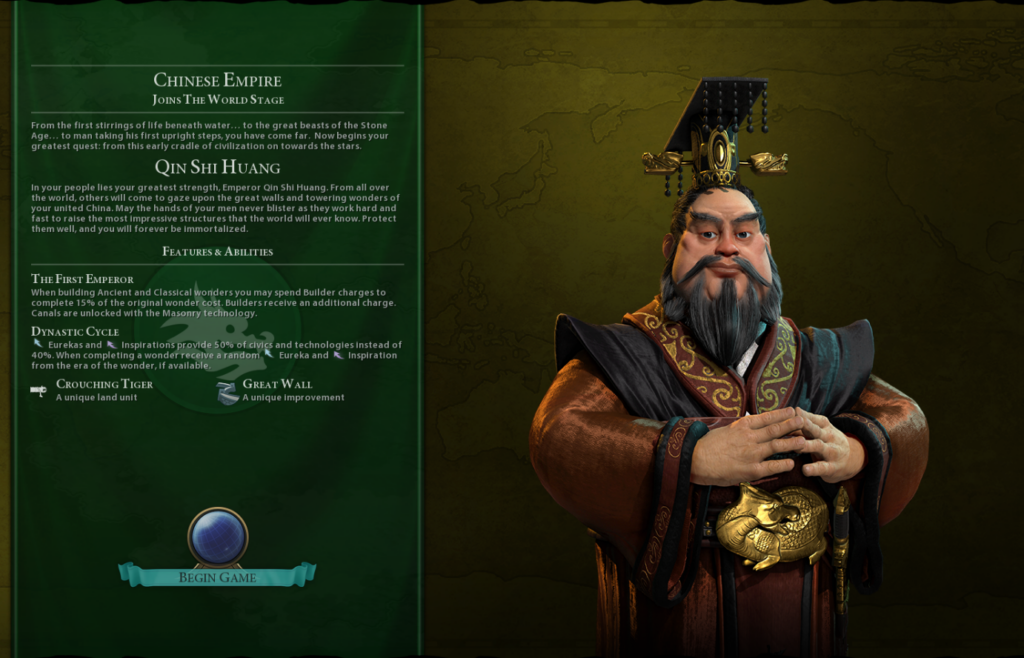

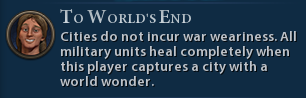

Similar to The Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI, the game also designed several traits particular to Chinese Civilization (See Appendix A, Figure 5). Besides assigning Ying Zheng as one of the representations of Chinese civilization, the game also created a distinct playing style for the player based on some of Ying Zheng’s accomplishments and policies. Though the traits containing the special land unit “Crouching Tiger,” come from later dynasties, and the “Dynastic cycle” draws from the Chinese alternation of dynasties, there are still “The First Emperor” and the “Great Wall” traits that draw directly from Ying Zheng’s reign. Later, we shall see how these two traits are reflected in the historical documents and what playing style the game designer encourages players to take in order to achieve final victory.

Understanding some basic gaming mechanics may be helpful to players on their way to victory. The game is a Marathonic competition, which extends from the Ancient Era to the Information Era and beyond. In the game, the civilizations’ abstract scientific and cultural production was represented by the Science and Culture numbers that can be generated from the cities and their facilities per round. A high Science and Culture production per round can help the players progress faster on the Tech Tree, and the Civic Tree simulates technology and societal progress. Progress along these trees is vital for the players who want to win the game through Cultural and Technology victory. As many of the cultures and technologies are produced in the facilities, the Production number that represents the cities’ productivity in constructing facilities is also an important factor. However, for those players who prefer military conquest, a high Production score can also help them construct a powerful army easily, which would help them sweep other competing civilizations and bring the players Domination Victory. Besides the three mentioned victories, there is also a Religious Victory that the players can achieve when their religion becomes the most followed religion for every civilization in the game. With a closer inspection of the Chinese Civilization under Ying Zheng’s leadership, we can see that though Ying Zheng’s traits did not directly contribute to a player’s effort in achieving any of the victories described above, they can gain higher productivity and multiple unique bonuses from the Great Wall, which make Ying Zheng available to achieve most of the types of victories.

As was discussed earlier, Ying Zheng ordered Meng Tian to construct a Great Wall that “followed the contours of the land and utilized the narrow defiles” to protect the empire from potential invasion.[25] Similarly, in the game, the Great Wall is also a unique construction of the Chinese Civilization, which can provide a defense bonus for its garrison units (See Appendix A, Figure 6). But historically, as time passed, those stone portions, which are “4-5 meters high and 4 meters wide at the base,”[26] became increasingly fragile against invasions launched by enemies in later centuries. Similarly, in the later stage of the game, the Great Wall could only provide very limited protection to the garrison units when facing the challenge of an attack by land units like Canons or Tanks. Although the Great Wall in the game may not be a good defensive means in later stages, other bonuses make the Great Wall a beneficial option for the players. The Great Wall in-game can also give the player the Culture production bonus and gold income. Besides helping the players more easily win a Culture Victory, the high Culture income itself would also boost the speed of the territorial expansion, which allows the players to have more available land for development. Besides the Culture production, the additional gold income brought by the Great Wall allows the player to maintain or purchase more land units, which assists their ambition of achieving Domination Victory. In other words, the construction of the Great Wall helps the players differently in the various game stages. In the game’s early stages, the Great Wall is a useful defensive fortification against the harassment of barbarians or other civilizations. In the game’s later stages, the Great Wall is transferred to become a financial and cultural booster, accelerating the player’s charge toward a Cultural or Domination victory.

Besides the Great Wall, the traits of “The First Emperor,” combined with two elements in Ying Zheng’s reign, also increased the Chinese Civilization’s general productivity. This game contains dozens of constructible “wonders” that drew models from the entirety of human history. Though highly time-consuming, the Wonders, once constructed, can bring the players magnificent bonuses in various areas of domestic and external affairs (See Appendix A, Figure 7). However, each Wonder could only be finished once per game, which means that if several civilizations compete for one Wonder, once one civilization finished the construction, the other civilization’s construction process would be immediately canceled, with nothing in return. As a zealot of massive construction who dispatched large labor forces to construct the “Replicas of palaces, scenic towers” and hundred rivers of mercury in his tomb, Ying Zheng in the game can accelerate the construction of Wonders by consuming laborers. [27] Though the laborers in the game are consumables that can be used in constructing the facilities three times, only Ying Zheng can use the laborers to accelerate the construction of ancient and classical Wonders. In comparison, he can also use the laborers four times rather than the normal three. This combination of Ying Zheng’s traits can also be seen as an echo of Qin’s corvee labor policy. According to Sima Qian, over “700,000 persons condemned to castration and convict laborers were called up” to construct the Epang Palace. At the same time, another “700,000 men from all over the empire” built the First Emperor’s tomb, and “all the artisans and craftsmen were shut in the tomb” by Huhai’s order.[28] Though the policy fueled people’s resentment against the empire and became the background of Meng Jiang’s sorrowful story, in the game, Ying Zheng’s traits, which were drawn out from the policy, again became the core of the Chinese Civilization’s playing style. Among the Wonders of the Ancient and Classical periods, there are Hanging Gardens that can accelerate the city’s development by 15%, or the Pyramids that can give players’ Laborers one additional charge. The additional productivity of Ying Zheng’s laborers, which comes from Ying Zheng’s special trait, can help the player reach other bonuses provided by the Wonders. Ying Zheng’s in-game traits became an omnipotent key for the players that can open the gate to multiple types of Victories.

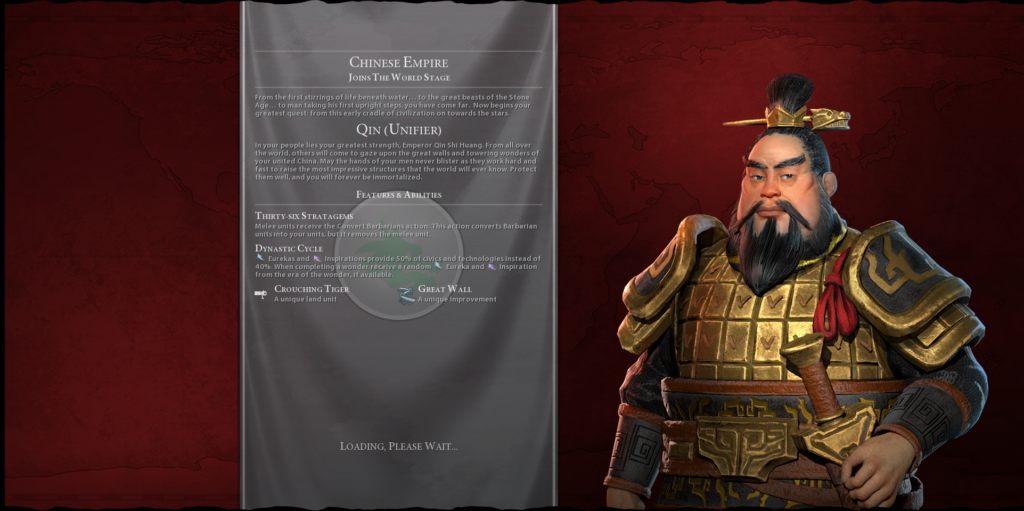

Some readers may feel that Ying Zheng’s traits in Civilization VI somehow neglected his empire’s accomplishment of “cracking his long whip and drove the universe before him, swallowed up the eastern and western Zhou, and overthrew the feudal lords.”[29] Thus, to enrich the gameplay for Chinese Civilization players, the game added another version of Ying Zheng, called the “Unifier,” in early 2023. As Appendix A, figure 8 presents, Ying Zheng, in his “Unifier” version, received a new war suit, with a new trait called “Thirty-Six Stratagems” replacing “the First Emperor.” The new trait allows Ying Zheng’s melee unit to transfer the surrounding Barbarian unit to Chinese units. The Barbarians are groups of non-alliance units scattered on the map that would indiscriminately attack players’ civilizations. Regardless of the lethal strikes launched by waves of Barbarians against civilizations located badly, Barbarians’ harassment in the early game stage did impede civilization’s development, especially towards civilizations that mastered development more than warfare. However, with the ability to transform Barbarian units, the Barbarians’ offense to Ying Zheng’s Chinese Civilization can be seen as an opportunity to enhance their force. This trait not only reminds players that Qin annexed “the land of the hundred tribes of Yue” while making their lords “bowed their heads, hung halters from necks and pleaded for their lives.”[30] It also echoes the debate around the concept of “sinicization,” as one of its major opponents, Evelyn Rawski, defined it as “the thesis that all of the non-Han peoples who have entered the Chinese realm have eventually been assimilated into Chinese culture.”[31]

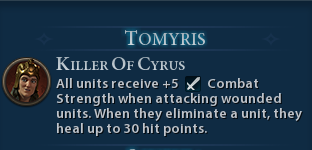

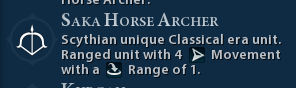

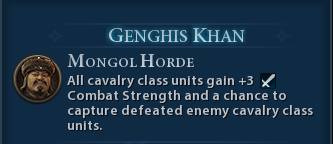

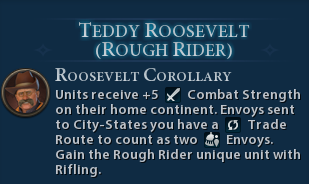

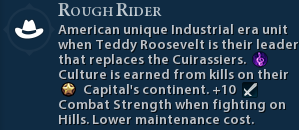

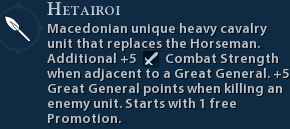

The two versions of Ying Zheng’s in Civilization VI can be generalized and fitted into the player-defined dichotomy of the “Berserker Civilizations -civilizations which perform better in combat-” and the “Farming Civilizations -civilizations which perform better in domestic development.” However, Ying Zheng also stands out in the game as his traits provide a distinguished route compared with other typical civilizations in farming and combat. In Appendix A, figure 9, readers can see some typical combat traits and unique units of leaders, including Tomyris, Genghis Khan, Teddy Roosevelt, and Alexander the Great. Among these traits and units, players may find that reinforcement on combat performance, which includes conditional Combat Strength bonus, unique advantageous units, and additional rewards for participating in combats, are some characteristics of a specialty designed for combat. For instance, the traits of both Tomyris and Genghis Khan encouraged them to hunt wounded units to either recover or strengthen their military force. Theodore Roosevelt, in his “Rough Rider” version, enjoys a mass Combat Strength bonus when fighting on his home continent. With the U.S.’s unique unit that provides prizes for kills on their capital’s continent, players of the United States in the game are both encouraged to and assisted in establishing dominance on their home continent. Similarly, as Macedonia receives a technology boost for its participants in combat, the players have more reasons to fight for technology escalation that can boost their combat performance with Macedonia’s unique units, which fight better than most of their potential opponents. In contrast to the leaders mentioned above, the “Unifier” Ying Zheng’s trait allows players to conditionally skip the combat with the Barbarians while similarly being awarded for the encounter. Though players playing as Ying Zheng are assigned fewer bonuses and prizes for direct armed conflict against other civilizations, they are encouraged to incorporate the Barbarians into their army. Besides easing the defensive pressure against the Barbarians, the trait also assists players in expanding on neutral territories scattered with Barbarians for a larger empire that can utilize more resources not only in combat.

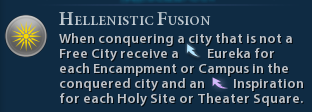

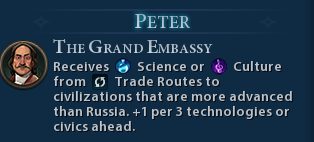

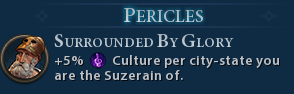

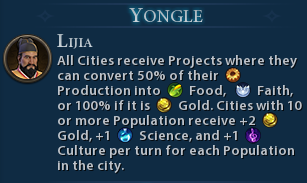

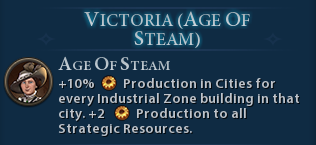

In Appendix, figure 10, readers may find that the design of typical “farming” traits also follows similar patterns. The traits of Peter the Great, Pericles, Yongle, and Victoria conditionally increase the outputs -including Food, Technology, Culture, or Production that can be transformed into the former three- in every round for players. Again, similar to his “Unifier” version, the original Ying Zheng stood out among his “farming” companions, as he was not assigned traits that numerically enhanced its output per round but was assigned the ability to utilize its laborers as agents in effectuating higher productivity. These designs on Ying Zheng’s traits, while being able to “model predictive systems”[32] referencing impressions on the Qin Empire and the entire Chinese civilization, also distinguished Ying Zheng from other leaders because of the trait’s direction and effectiveness.

Combining Ying Zheng’s two versions in Civilization VI, we may again see the structure of Shang Yang’s “Agriculture and War.” In the game, the Chinese Civilization represented by Ying Zheng had strong productivity bonuses in the wider concept. The players have considerable advantages in competing with the Wonders in the Ancient and Classical periods or absorbing the Barbarian units and territory into their growing empire. After enjoying the bonus from an early stage of the game, players in the later stage would start to enjoy the Culture and the Gold produced from the construction of the Great Wall, which helps the player have the power and potential to chase victory in various spheres. For the Chinese Civilization in Civilization VI, the “war” part becomes a relevant result of an efficient and beneficial “agriculture” process supported and improved by Ying Zheng’s traits. This abstract “war” is not limited to conquest and Domination, as the “agriculture” part provides Ying Zheng and his civilization with resources in multiple spheres. Thus, the Chinese civilization can compete with other civilizations in Culture, Science, Domination, or even the Religious sphere, allowing players to find their paths to the final victory.

After discussing Qin’s traits in both Romance of Three Kingdoms XI and Civilization VI in detail, perhaps some readers have already noticed the state perspectives of both games. Both games give some sense of reality to provide players with “fun challenges” of conquering and domination or the “emotional effect” of leading civilizations to thrive.[33] Both games “pivot” on abstractions for players’ benefit. Those who are leading the polities or civilizations in the game are neither the commoners, generals, nor the nominal “leaders.” It was the players who received the highest freedom and power to execute their ambitions as the actual leaders of their virtual state. More accurately, “the virtual states are the players.” The Laborers in Civilization VI never resist when seeing a player “consuming” their companions for Wonders. The civilians in Romance of Three Kingdoms XI did not resist when a player assigned Ying Zheng to tax them 50% more than before or when the player’s miscalculation emptied the city’s food storage. Ying Zheng, though regarded as the representative of the Qin Empire or the Chinese civilization in games, is a puppet assisting players with his unique traits, not with the ability to make decisions. This concentration of power happens between the players and their virtual polities, interestingly another part of Legalism: the sense of “oneness.” This “oneness” does not mean that the legalist excludes the civilians or the officials aside from the legalist blueprints. The opposite is true. According to Fung Yu-lan, the legalist school taught “the theory and method of organization and leadership.”[34] However, as these theories are centered on strengthening the emperor’s control of his subjects, Fung Yu-lan believes that “only” those who wish to organize and lead their people “following totalitarian lines” would find the Legalist theory “still instructive and useful.”[35] Shang Yang, in his article “The Unification of Words,” promoted the “single-mindedness of the people” in “administrating” a country while emphasizing the importance of “consolidating” the country’s “primary occupations” to make its people “take pleasure in agriculture” and “enjoy warfare.”[36] To Shang Yang, the “right way” of a country is “concerned with weakening the people,” as “a weak people means a strong state.”[37]In both games, readers can see the abstract—and in some sense, oversimplified—representations of civilians under current mechanisms, which made them even more idealistic than the legalist theoretical work. The abstract civilians in both Civilization VI and Romance of Three Kingdoms XI “enjoy service” even when being governed without “means of punishment;” they “scorn death” even when being“made to fight” without “means of rewards.”[38] To the legalists, the government officials are both the companions of the ruler and the subject of the ruler’s power concentration.[39] According to Shang Yang, “three things” can bring an “orderly government” to the state. These three things include “Law,” which “is exercised in common by the prince and his ministers,” and “Good faith,” which “is established in common by the prince and his ministers.”[40] The last thing, “the right standard,” is defined and “fixed by the prince alone,” while “there is danger” if a ruler “fails to observe it.” Meanwhile, Shang Yang believes that the rulers who “dismiss the law and place reliance on private appraisal” bring “disorders in a state.”[41] Similarly, though within the games, players may see their officials united under the “good faith” of winning the game within the games, the true power is always held in players’ grip. The officials in the game are the executants of the player’s orders, sometimes giving advice that may affect the players’ decisions, but only the players are decision-makers. Han Feizi discussed the idealistic rulers who can “carry out his regulations as would Heaven, and handles men as if he were a divine being.”[42] Thus, the ruler “commits no wrong” and “falls into no difficulties.”[43] The players are like “divine beings” as they may have hundreds of hours of experience before starting a new round of games or instructions from content providers on game forums or video websites.[44] Even if the players are new to the game, the save & load mechanism allows players to make reckless tries without the risk of the nation’s downfall. Thus, the players in both Civilization VI and Romance of Three Kingdoms XI, regardless of the polities or civilizations they played as, displayed a legalist blueprint of state management. The emotionless and uniformed groups of commoners were organized and led by a group of carefully selected officials who had various benefits and manageable loyalty to their supreme leader. Players, the leaders, having almost every aspect of their virtual states in control, take their monopolized power of driving the entire state, driving the state for escalating national power, and competing with other polities in games that, most of the time, could only have one winner.

Through a detailed survey, readers can see that the Qin characters in both games had unique traits, distinguishing them from other characters and contributing to the player’s struggle for the final victory. Though not presented as the top polities on the battlefield, Qin was designed with its magnificent focus on “farming,” which encourages players to empower their virtual state first before competing with others in supreme national power. Aside from how Qin’s in-game road to victory mirrored the Legalists’ ideas of “Agriculture and War,” players’ interactions with their virtual states also reflected the Legalist idea of “oneness.” In command of the players who are equipped with the game understanding and can hardly make any irreparable mistakes, the civilization and empires are like precise machines. With groups of civilians represented by abstract numbers almost unconditionally supporting the player’s ambition, players, as the only decision-makers in the game, became the actual representatives of their virtual states.

Appendix A: In-game Screenshots

This appendix consists of the in-game screenshots that are essential for the discussion of the Qin

Figure 1. Ying Zheng character interface from Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI[45]

Figure 2: Li Si character interface from Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI[46]

Figure 3: Meng Tian and Wang Jian character interfaces from Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI[47]

Figure 4: Bai Qi and Zhang Yi’s Character interfaces from Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI[48]

Figure 5: The construction progress difference between Meng Tian (right) and one general without the Construction trait(left)[49]

Figure 6: Ying Zheng’s traits in Civilization VI[50]

Figure 7: An example of the Great Wall in Civilization VI[51]

Figure 8: Chinese civilization, with Mt.Saint Michel, Taj Mahal and Stonehenge around its capital Xi’an[52]

Figure 9: Ying Zheng as the “Unifier.”[53]

Figure 10: Combat traits and unique units from leaders including Tomyris, Genghis Khan, Teddy Roosevelt, and Alexander the Great.

Figure 11: “Farming” traits from leaders including Peter the Great, Pericles, Yongle, Trajan and Queen Victoria.

© 2023 The UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History

[1] Having completed his undergraduate studies as a History major at UCSB, Vassili Zou is currently pursuing a master’s degree at New York University’s East Asian Studies program. His academic interests lie in investigating the reinterpretation of historical events within modern Chinese internet society.

[2] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Volume, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), p. 93.

[3]Krijn Boom, “Teaching through Play: Using Video Games as a Platform to Teach about the Past,” in Communicating the Past in the Digital Age ed. Sebastian Hageneuer, (Ubiquity Press, 2020), p. 28.

[4] Boom, “Teaching through Play: Using Video Games as a Platform to Teach about the Past,” p. 31.

[5] Anthony Barbieri-Low, The Many Lives of the First Emperor of China, (University of Washington Press, 2022), p. 218.

[6] Barbieri-Low, The Many Lives of the First Emperor of China, p. 24.

[7] Yuri Pines, “Bias and Their Sources: Qin History in the “Shiji”,”Oriens Extremus, Vol.45 (2005/06): p. 30.

[8] Pines, “Bias and Their Sources,” p. 11.

[9] Martin Kern, “Announcements from the Mountains: The Stele Inscriptions of the Qin First Emperor,” in Conceiving the Empire: China and Rome Compared ed. Fritz-Heiner Mutschler, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 226.

[10] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[11] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, pp. 82, 234.

[12] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Volume, pp. 64-65.

[13] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 239.

[14] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 258.

[15] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 263.

[16] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 177.

[17] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 275.

[18] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 177.

[19] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, pp. 275-276.

[20] Shang Yang, The Book of Lord Shang: A Classic of the Chinese School of Law, trans, J.J. Duyvendak, (London: Probsthain, 1928), p. 185.

[21] Barbieri-Low, The Many Lives of the First Emperor of China, p. 37.

[22] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Volume, p. 93.

[23] Firaxis Games, Civilization VI, Firaxis Games, PC, 2016.

[24] Peter Krapp, “Sid Meier’s Civilization: Realism” in How to Play Video Games ed. Matthew Thomas Payne, (NYU Press, 2019), p. 226.

[25] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 275.

[26] Tang Xiaofeng. “A Report of the Investigations on the Great Wall of the Qin Han Period in the Northwest Sector of Inner Mongolia.” (Wenwu, 1977.5), p. 960.

[27] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 97.

[28] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, pp. 88, 97.

[29] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 117.

[30] Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, p. 117.

[31] Evelyn S. Rawski, “Reenvisioning the Qing: The Significance of the Qing Period in Chinese History”,” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 55, No. 4 (1996): 842.

[32] Krapp, “Sid Meier’s Civilization,” p. 45.

[33] Aris Politopoulos, “Video Games as Concepts and Experiences of the Past,” in Virtual Heritage: A Guide, ed. Erik Malcolm Champion, (Ubiquity Press, 2021), p. 82.

[34] Fung Yu-Lan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, (New York: The Free Press, 1966), p. 157.

[35] Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 157.

[36] Shang, Book of Lord Shang, pp. 234,236.

[37]Shang, Book of Lord Shang,p. 303.

[38]Shang, Book of Lord Shang,p. 306.

[39]Shang, Book of Lord Shang, p. 260.

[40]Shang, Book of Lord Shang,p. 260.

[41]Shang, Book of Lord Shang, p. 262.

[42]Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 158.

[43] Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 158.

[44] Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 158.

[45] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[46] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[47] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[48] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[49] KOEI, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, KOEI. Wii/PC. 2006.

[50] Firaxis Games, Civilization VI, Firaxis Games, PC, 2016.

[51] Firaxis Games, Civilization VI, Firaxis Games, PC, 2016.

[52] Firaxis Games, Civilization VI, Firaxis Games, PC, 2016.

[53] Object Software, Prince of Qin, Object Software, PC, 2002.