A Murderous Gang in the Hills of L.A

Welcome to “Headline History” by the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History. Ava Thompson writes today’s story. I want to transport you back to Santa Barbara in 1857. You just opened the morning paper, and a story jumps out at you titled “Great Excitement in Los Angeles! The Sheriff and Three Men Killed!”. One hundred and sixty-eight years later, a history major will notice the very same headline, just this time, it will be on a MacBook Air.

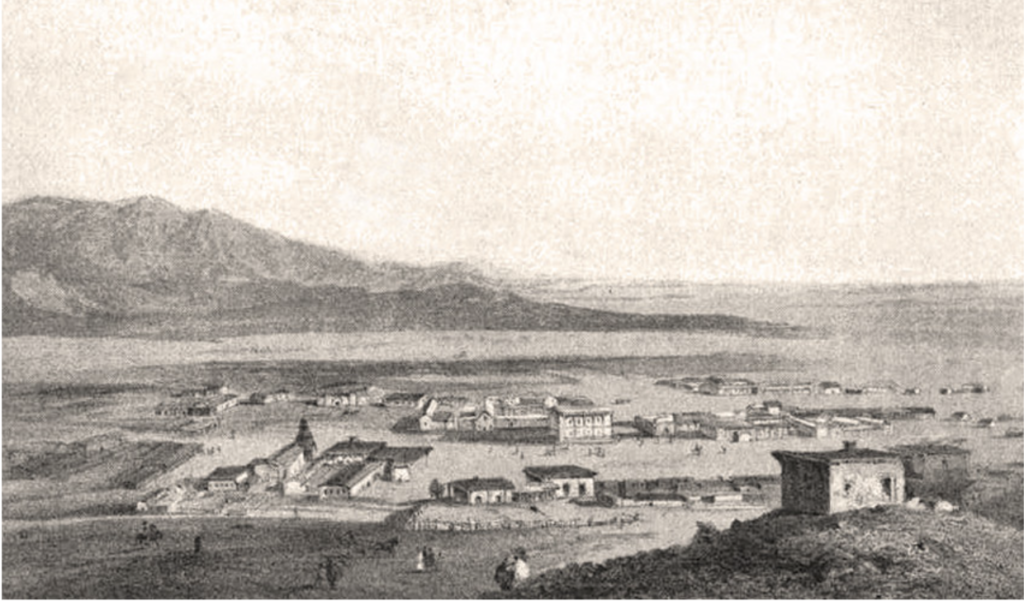

Let’s set the scene for today’s story. Imagine Los Angeles today: A vast, sprawling city pumping influencers, the hottest trends, and movies through its main artery, the 405. And slowly, if you can, imagine all the mansions disappearing from the sloping hills, leaving them bare and soft with wild grass, flowers, and dry trees. The valley is void of shopping malls, and suburbia simply scattered farms and settlements. Now downtown and towards the water, the dense housing and freeways lift away and are replaced with open space. Small streets are lined with low buildings, small businesses, and family homes. In Los Angeles County in 1857, the population would have been around 10,000. Just 20 days earlier, the Fort Tejon Earthquake had hit—one which has since not been out quaked in California. While the ground was shaking and the population was on the rise, crime was making an impression too. That is where our story begins.

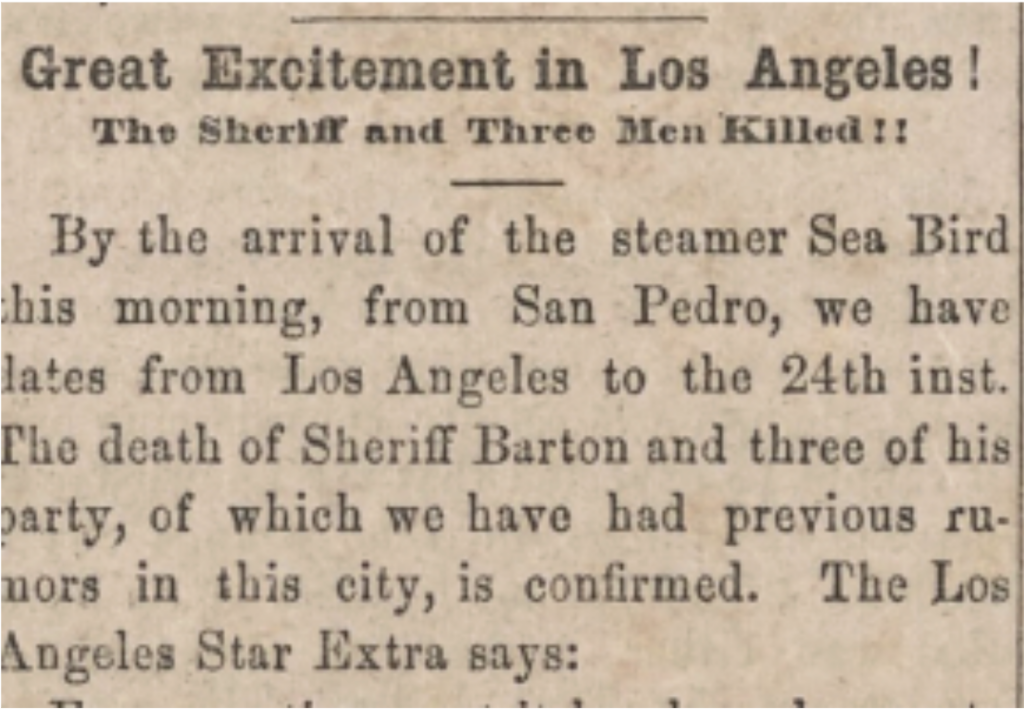

On 29 January 1857, the Santa Barbara Gazette reported that a murderous gang was in the hills of Los Angeles, and they killed the sheriff. Days earlier, a young man, Garnet Hardy, got word in San Pedro that a murderous gang was nearby. He wrote to his brother, who told the Los Angeles Sheriff, J. R. Barton, Esq, that the gang had been blitzing the area, robbing stores, and killing homeowners. In one case, they allegedly ate dinner at a man’s table next to his dead body!

The sheriff and his party of six men arrived at Sepulveda’s Ranch, where the owners warned them not to go any farther or else they would be killed. The party ignored this advice, and the paper details the consequences: “about twelve miles from Sepulveda’s ranch, at a spur of the San Joaquin Ranch Mountain, they were suddenly attacked by a band of robbers, at least twenty in number, who rushed out from between the hills”(Santa Barbara Gazette). Only two of the men lived to tell the tale.

A band of forty men left L.A. in pursuit of the killers but failed to find the culprits. The story was updated on February 5th, the next issue. In good news, they reported that the murderous gang members had been apprehended through a considerable effort by volunteers and police. In this update, they took a firmer stance on crime, stating, “The lawless gangs should be exterminated if that city desires prosperity, and it is their bounden duty to do this; and we shall be happy to chronicle the highly desirable event” (SB Gazette). Interestingly this statement gives the impression that Santa Barbara itself may have felt it found this so-called “prosperity.” While this story may have incited fear in residents, the paper seems unconcerned with the city’s ability to deal with these types of crimes if they arose. Santa Barbara residents may have had a new vigilance knowing these opportunistic gangs were near their hometown.

The following two issues report that the gang’s leaders escaped prison but were recaptured and executed. Over forty men were arrested, and twelve were executed by hanging. Little detail is given on the escapees, but readers surely would have felt discomfort knowing that they were only a few cities over in the route of a dangerous man on the run.

In reporting this story, the Gazette was eager to thrill their readers with tales of crime. Although they sometimes take a turn for the sentimental or moral, the story was written to excite. While fear was undoubtedly a factor in the consumption of this news, readers must have taken comfort in the capital punishment enforced on the criminals. There may not have been much entertainment locally in 1857’s Santa Barbara, so as the reader closes his newspaper, he may have planned how to regale the tale to his neighbors or family. Though there is still crime in Santa Barbara, often, our days seem idyllically far from big city life and commotion.

Ava Thompson

Ava is a third-year History of Public Policy and Law major with an English minor. She is an editor at the journal, on the Environmental Affairs board, and a member of UCSB’s Pre-Law Fraternity. Ava is passionate about bridging creative writing and historical analysis in her work at UCSB. In her free time, she does amateur painting, leisurely swimming, and loves to watch reality tv with friends.