Decades of Change: Women’s Studies’ Origins Through the Lens of Gauchos

In 1970, the United States saw the creation of its first-ever university-level Women’s Studies department at San Diego State University. At this point, the topics covered by the discipline had long been neglected in American public and private education, with women’s voices and experiences left to the footnotes of academia. But as the second wave of feminism swept the nation in the 1960s, women from every walk of life began demanding their place in systems of power. In this feature of our Headline History Blog, we’ll dive into the development of Women’s Studies at another California university by the beachside: UC Santa Barbara.

In 1971, the UCSB Daily Nexus published one of the newspaper’s first mentions of feminist activism. In a brief article, a reporter discussed the start of the university’s brand-new Women’s Center, replacing a former fraternity. All of the controversy and praise its founding garnered among students. In one reference to the new center, students referred to it as a “place to share ideas” on the Women’s liberation movement, while others saw it as the place “where THEY are trying to take over US.”

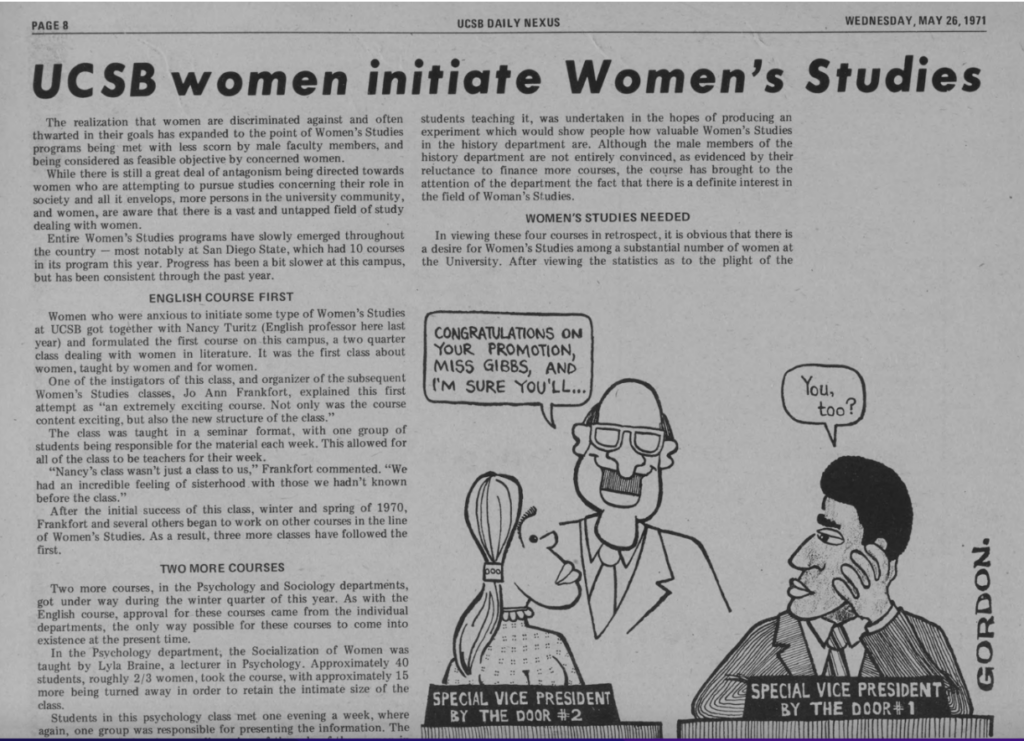

Later in the last half of that same edition, the Nexus spotlighted the development of Women’s Studies at SDSU and the need for the department at UCSB beyond the few Women’s Studies courses offered at the time.

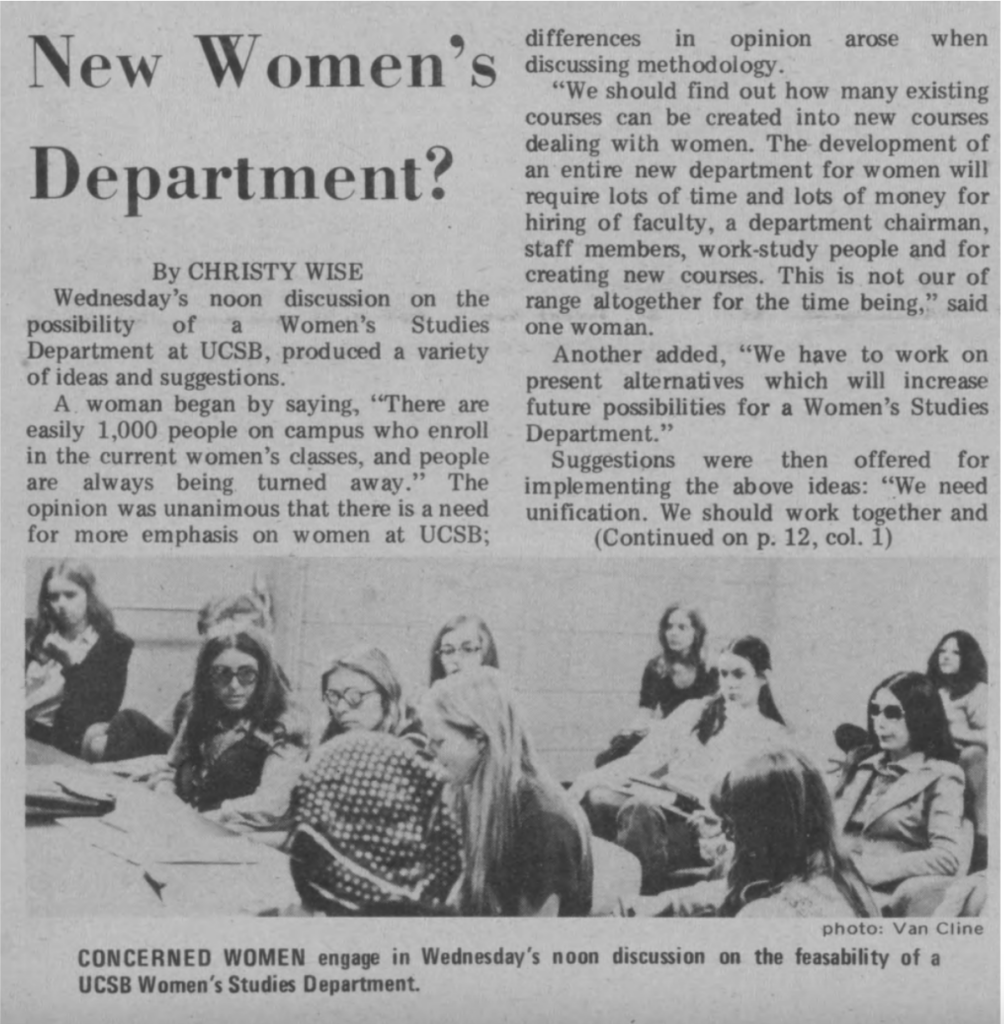

Despite an emerging interest in the subject, Gauchos would go without the opportunity to pursue a degree in Women’s Studies for years after this article. This piece was likely many students’ first introduction to the very idea of the discipline. Nearly a year later, as the campus population became more familiar with and gradually more used to the Women’s Center’s presence, talks of bringing about a Women’s Studies major of their own to the university hit the front page headlines of the newly rebranded Daily Nexus.

As the movement gained momentum, the country saw the landmark decision of Roe v. Wade and its revolutionary impacts on bodily autonomy. On a smaller scale, Gauchos found their own way of joining the national conversation: adding the “Woman’s Voice” section in 1973. While this was not the first instance of the Nexus showcasing female voices, it was one of the paper’s first designated spaces for uplifting women on campus. This section would frequently recur over the next few years of the paper’s run in many different forms. Still, its first iteration focused on reflecting on the female liberation movement and all the work ahead of it.

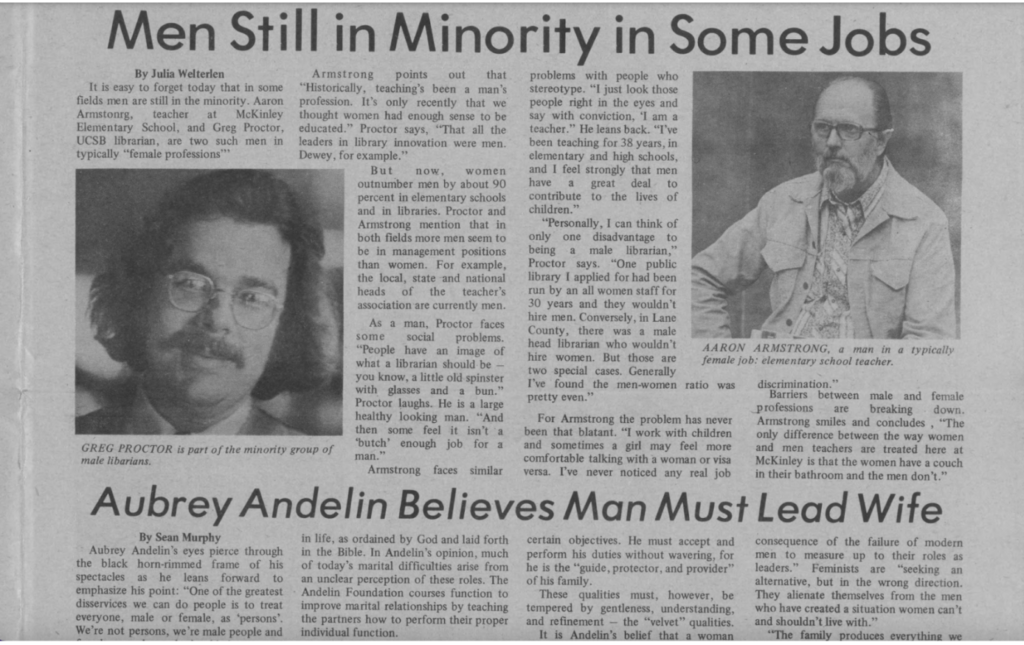

At this point, progress seemed almost inevitable if one were only to base this conclusion on the newspaper’s regular reporting on feminist issues, diversity in academia, and women in faculty. Unfortunately, for the latter half of the 70s, these issues would be delegated to the back pages more often than not, previewed by articles that not only outshined them but sometimes outright demeaned them. One such headline appeared in a February 1977 issue on men as the minority:

While articles focusing on men as the minority in professional settings would certainly not become the primary reporting of the Nexus, many like it followed in subsequent editions. The next decade of print would find ways to balance blatant criticism of women’s voices and openly advocate for them. With every male-centric think piece to be published, there was a short and well-meaning piece by a feminist writer, constantly calling for more coverage of women in academia, though never outright proposing the Women’s Studies department the paper had once suggested a possibility.

In February of 1987, the first statewide conference on Women’s Programs took place on the campus of UC Los Angeles. By this point, the national movement for women’s liberation had died down significantly, and the public had lost a reason to care about the fight. The Nexus was not far behind on this sentiment and devoted less than half a page to this monumental event in developing Women’s Studies. There were few reports on UCSB’s participation, most only alluding to the department’s development, which the university had officially sanctioned.

Following this trend, the department’s official opening received one of the smallest coverages of any feminist issue:

The coverage came after the discipline’s year anniversary as part of the university’s curriculum. Without announcing its existence in the preceding issues, the Nexus placed the new track of study as an afterthought once again, just as it had started nearly two decades prior.

In exploring UCSB’s student papers, we can see a path of progress that should not be discounted for what it was at the time: a step forward. But as today’s generation of students continues to fight for bodily autonomy across the country, representation in our fields of study, and intersectionality in every aspect of education, it’s clear to see that the introduction of Women’s Studies was just one of many steps towards ongoing equity in academia.

Anna Friedman

Anna is a third-year History major minoring in Religious Studies. Her historical interests are in Russian and Eastern European studies and Feminist studies. In her free time, she works as a peer advisor at the UC Santa Barbara College of Letters and Science, as well as doing research for the English Department, planning and running events for student organizations, and participating in Goodreads’ yearly book challenge.