On June 29, 1925, a strong earthquake struck Santa Barbara with great devastation. Although the old Chinatown was slightly destroyed, prominent white property owners and the city council conspired to demolish the rest of Old Chinatown. They envisioned creating a cohesive Spanish Colonial Revival look for downtown and facilitating tourism in Santa Barbara. According to the Santa Barbara Daily News, this measure aimed to end the constant Chinese internal conflicts to ensure safety and harmony for the local community. In 1927, newspapers announced that Old Chinatown had gone with the winds.

Today popular perception is that the history of Santa Barbara’s Chinatown immediately faded after the 1925 earthquake. Like other parts of the city, Chinatown was rebuilt, sponsored by a cohort of Chinese merchants and a local real estate owner and contractor named Elmer Whittaker. Whittaker built a series of structures one block away from the old Chinatown, and the new area is known as the “New Chinatown.”

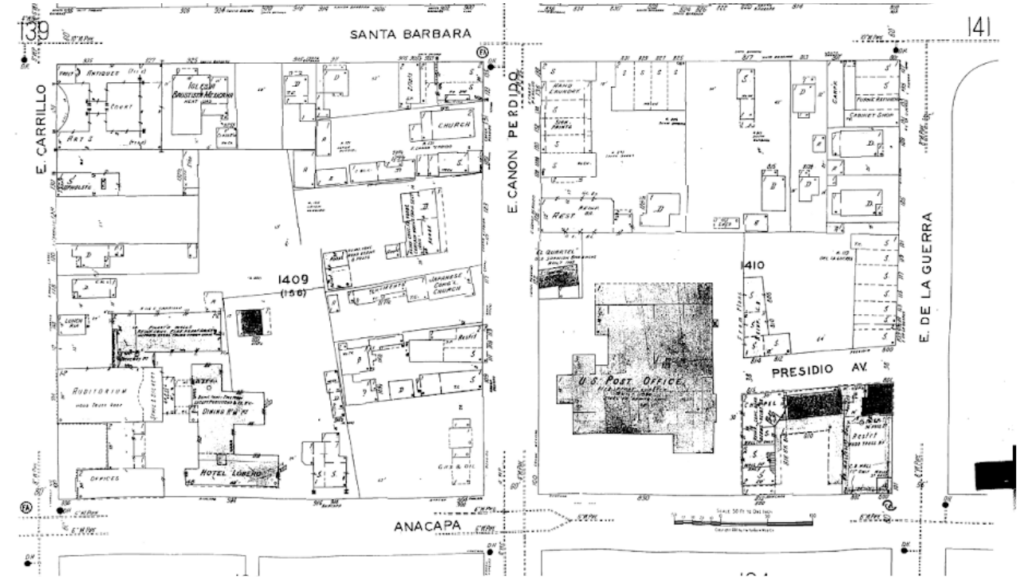

Ella Yee Quan, a Santa Barbara native, recalled her life in New Chinatown. Storefront businesses were on the ground floor, while residences were on the second floor. The first building had 12 units on East Canon Perdido Street, and the second had eight units located on Santa Barbara Street. A Chinese language school, a Chinese boys club, grocery stores, restaurants, laundry, herbal stores, general merchandise stores, cigar stores, and Tong associations (Chinese benevolent societies) dotted the streets.

During the Great Depression and World War II, this business hub slowly faded as the local Chinese population declined. Yet one Chinese-owned restaurant, Oriental Gardens, was an outlier that thrived for decades, demonstrating how Chinese immigrants in Santa Barbara survived and searched for inclusion in the United States.

The owner, “Jimmy,” James Yee Chung, was born in the Canton province of China in 1910 and moved to Santa Barbara as a young man during the Chinese Exclusion period (1882-1943). Under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, common Chinese people could not migrate to the United States. Yet, a few exempted classes, such as merchants, students, diplomats, and visitors, were permitted to enter the country. These immigrants were also allowed to bring their wives or children to the U.S. Jimmy Chung utilized his family networks and his father’s identity as a laundry owner, who was considered a merchant then, to enter the United States. He then worked at his father’s laundry in San Francisco for a few years, and after the end of WWII, he moved to Santa Barbara. Jimmy operated restaurants on State Street and Cabrillo Boulevard before moving his business to Canon Perdido Street in 1947 at the encouragement of Elmer Whittaker. He and Mr. Whittaker built the restaurant and residence behind it in 1946. To American observers, the original restaurant was in a “strange, and not yet so strange” contrast with the Spanish-style neighborhood.

Strange as the restaurant might be, the Chung family and Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens have been crucial to the diverse community living and working within the Presidio Neighborhood. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the area in and around the Santa Barbara Presidio was a multi-ethnic neighborhood. In addition to white Americans, Chinese, Mexican, and Japanese residents also made homes or worked here. From the postcard of Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens, we could tell this restaurant was aimed to serve food for both Chinese and American populations. The Chinese-language slogan, or “duilian” in Chinese, put up at the front of the door, read, “People from near or far places will enjoy themselves a lot in the restaurant; People in the East and West will develop friendships here.” The interior of the restaurant was decorated in an eclectic style as well. Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens mainly used blue and green walls, unlike most Chinese restaurants, which were primarily furnished in traditional red, gold, and black. Chinese paintings and lanterns were hung on the walls. White tables and orange-colored chairs were placed, with chopsticks, forks, knives, and napkins on top of the tables. The cashier counter was retro-styled with a coin-operated phone. But the most exciting part of the restaurant is the bar, and according to some oral accounts of the previous residents, it has been an exciting place for the working class to relax after they return from a day’s hard work.

https://alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f3kw5d8g

When Jimmy Chung died in 1970, his son, Tommy Chung and Tommy’s wife took over the restaurant’s management. And the restaurant remained in place to serve the community until 2006. In 2010, the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation purchased Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens for public education and exhibition. Nowadays, if you walk on East Canon Perdido Street, right across the El Presidio historical site, next to the Handlebar Coffee, you will see a restaurant called the Three Pickles. That’s where you could sense the once-flourished Chinatown in old Santa Barbara.

A Photograph of Three Pickles, courtesy from Santa Barbara Independent.

Keren Zou. Keren is a senior undergraduate student at UCSB, triple majoring in History of Public Policy and Law, Asian American Studies, and Geography. Her research interests include American Race & Immigration History, nineteenth-century U.S. History, and Food History. Keren plans to pursue a doctoral degree in History. Besides researching and working as a student journal editor, Keren enjoys cooking, gardening, and traveling with her friends.

Santa Barbara’s city map in 1950. It demonstrates the Cannon Perdido neighborhood was very multi-ethnic and thriving. For example, you can see Chinese hand-wash laundry, Japanese Christian church, Mexican meat shop, U.S. Post office, El Quartel Spanish historic site. Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens, located on 126 E. Canon Perdido, was almost in the center of the community!