Like the well-known electric trolley attraction in San Francisco, there was once an electric streetcar system in Old Santa Barbara. On October 1, 1896, Santa Barbara’s citizens welcomed the city’s first electric streetcar system in downtown SB. The newspaper Daily News reported that the mules (horse-drawn carriages) had ceased to be a mode of transportation, and the city turned a new leaf in its history.

The advent of the electric car line began operations under favorable conditions. Along with the prosperity of tourism in Santa Barbara during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the streetcar helped connect famous travel destinations and local businesses on State Street. The original line stretched from the Stearns Wharf in the waterfront area to Arlington Hotel, the center of Downtown SB.

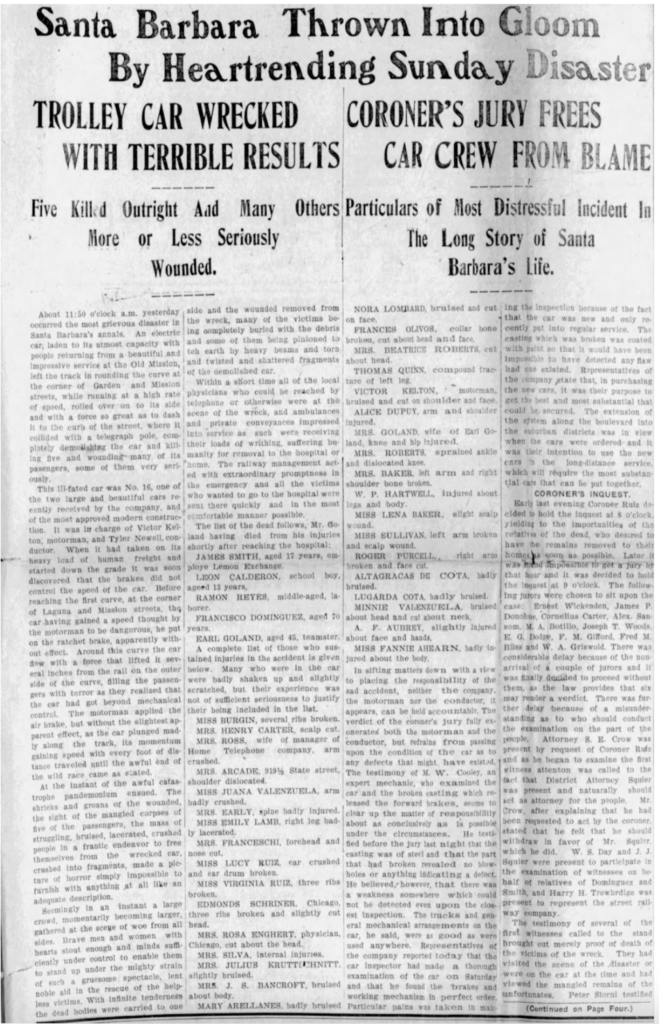

Despite the economic prospects of the new mode of transport, an unexpected consequence began to come to fruition: accidents. In 1904, one “mysterious” electric street car accident resulted in 5 deaths and at least 34 people injured. On April 10, 1904, an electric street car filled with passengers ran on its designated orbits as usual. Then at 11:50 am, the car suddenly abandoned the track at the corner of Garden and Mission streets. It darted at high speed, rolled onto its side, and slid toward the street’s curb, colliding with a telegraph pole, completely demolishing itself.

According to the Santa Barbara Independent, the car was one of the streetcar company’s two recently purchased “large and beautiful cars. However, because it had been overloaded with freights and passengers upon its operation, the brake of the streetcar seemed to have been degraded.” Although the motorman attempted to control the car with the brake, the car “plunged madly along the track, gaining speed with every foot of distance traveled until the awful end of the wild race.” The catastrophe happened in a moment, becoming one of the “most stressful incidents in the long history of Santa Barbara.”

But the real cause of the accident remained ambiguous after the Coroner and jury exonerated the employees of the streetcar company. Victor Kelton, the motorman, who ended up with his head in bandages and tortured by physical and mental distress, was exculpated by the verdict of the coroners’ jury. The streetcar company guaranteed that it had made every effort to obtain the best-equipped and secured streetcars for its passengers. And Its claim was further accredited after the juries appointed an experienced technician to scrutinize the conditions of streetcars, where he found all the parts of the streetcars (including the brakes) were sturdy and defectless.

Although the jury exonerated the company, the passengers’ relatives were traumatized and outraged by the accident. One of the victims was Earl F. Goland. His widowed wife filed a lawsuit against the Santa Barbara Consolidated Railway company for $25,000 in compensation. In her appeal, Mrs. Goland accused the streetcar driver of “carelessly and negligently operating” the streetcar, and her husband was thrown to the ground from the track with great force and violence.

Local residents rendered generous support and aid to the victims and their relatives. The Old Mission at Santa Barbara held a requiem for the deceased on April 15. They expressed their heartfelt sympathy and condolences to the relatives of the victims and prayed for the souls of the deaths. Newspaper media also kept track of the well-being of the victims. Mrs. Baker and her daughter Miss Anna Sullivan were both severely wounded by accident. James Quinn’s left leg was crushed by the electric streetcar, and remained frightened after the accident, worried he would be disabled forever. Newspapers continued to report their stories until their conditions got better if they did.

Despite this heartbreaking accident, the streetcars remained in service until the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake drastically disrupted the city’s buildings and infrastructure. It entirely ceased operations in 1929. Today, when people were wandering in the hustling and bustling State Street in downtown Santa Barbara, it should also be remembered that there was a significant chapter of the streetcars in the city’s transportation history!

Keren Zou. Keren is a senior undergraduate student at UCSB, triple majoring in History of Public Policy and Law, Asian American Studies, and Geography. Her research interests include American Race & Immigration History, nineteenth-century U.S. History, and Food History. Keren plans to pursue a doctoral degree in History. Besides researching and working as a student journal editor, Keren enjoys cooking, gardening, and traveling with her friends.