The Power of Collective Liberation: Inside the Combahee River Statement

Olivia Roth

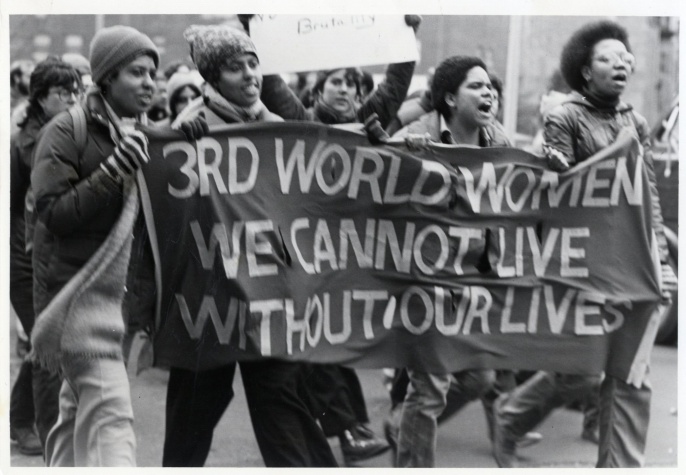

The Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s and ’70s was a collective alignment of women and feminists who sought to empower, advocate for, and champion women in the fight for equal rights. Yet the movement often marginalized other women—particularly Black women—who were simultaneously engaged in the Civil Rights Movement and second-wave feminism. In practice, the feminism of the Women’s Liberation Movement frequently mirrored the very systems it aimed to dismantle: hierarchical, exclusionary, and blind to difference. These internal exclusions sparked the emergence of Black feminist groups like the Combahee River Collective, which responded by developing their own distinct agendas and visions for liberation.

The Combahee River Collective was a radical Black feminist writing group formed in 1974. Born out of dissatisfaction with the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), the group’s founders cited serious disagreements with NBFO’s bourgeois-feminist stance and their lack of a clear political focus. The Collective crafted an analysis of oppression that was more expansive and intersectional than most of its contemporaries, tackling issues like Black heterosexism, homophobia, and queer rights in ways that had not yet been widely addressed. A core principle of their work was the recognition that not all women had the same experience of gender—an insight that became foundational to Black feminist thought.

In 1977, members Barbara Smith, Demita Frazier, and Beverly Smith co-authored The Combahee River Collective Statement, a defining text in the history of Black feminism and one of the earliest articulations of what would later be known as intersectionality. Although the term had not yet been coined, the statement laid out a framework for understanding how interlocking systems of oppression—racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia—shape the lived experiences of Black women. It also offered a powerful critique of the mainstream feminist movement and introduced a blueprint for a more inclusive and liberatory politics.

The statement is divided into four sections, each of which builds on the others to outline the history, beliefs, challenges, and political vision of the Collective. The first section, “The Genesis of Contemporary Black Feminism,” asserts that Black feminism has a deep and enduring history, emphasizing that Black women have always engaged in feminist resistance. The authors point out that every Black feminist has a personal “genesis” story—a moment when they recognize and validate their experiences of oppression. As they write, Black women occupy a distinct position that demands “a politics that was anti-racist, unlike those of white women, and anti-sexist, unlike those of Black and white men.”

The following section—“What We Believe”—describes the collective’s guiding principles. It stresses that Black women are inherently valuable and that liberation is essential. Additionally, it introduces a new analysis of oppression: identity politics. The authors define this as political action based on a particular identity, writing that “the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.” This term recognizes the significance of organizing against multiple oppressions and finding belonging within one’s intersecting identities. The Collective also makes the fundamental argument that liberation necessitates the dismantling of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy and asserts that for the Women’s Liberation Movement to succeed for all, it needs to take into account “the specific class position of Black women who are generally marginal in the labor force.”

This idea leads to the third section: “Problems in Organizing Black Feminists.” Here, the authors address the complicated layers of oppression that Black women function under and are determined to dismantle. It is here that arguably the most famous line is written: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” This was not just a call for solidarity; it also redefined liberation itself. Yet it also highlighted how hostility within the Black community created yet another obstacle to the development of a unified organizing strategy: sexism. The authors write that Black men “realize that they might not only lose valuable and hardworking allies in their struggles but that they might also be forced to change their habitually sexist ways of interacting with and oppressing Black women. Accusations that Black feminism divides the Black struggle are powerful deterrents to the growth of an autonomous Black women’s movement.”

The fourth and final section—“Black Feminist Issues and Projects”—directly confronts racism within the white feminist movement. It argues that white women bear the responsibility of ending racism and stresses the importance of coalition-building across race, gender, and class lines. In doing so, the Combahee River Collective Statement laid the foundation for a long-lasting legacy in Black feminist thought and intersectionality. It inspired many feminist grassroots organizations, truly reshaping the future of feminism.

In a 2021 interview with Marian Jones for The Nation, Demita Frazier described the statement as being about “dismantling power structures,” while Barbara Smith emphasized “that all oppressive systems affect Black women”. Their insight and the Combahee River Collective Statement remind us that the Collective’s work remains urgent and unfinished. By naming the specific forms of oppression Black women face — and insisting that liberation must address them all — the Collective inspired many feminist grassroots organizations, truly reshaping the future of feminism.

Author bio: Olivia Roth graduated with her Bachelor’s in History from UC Santa Barbara in the Winter of 2025. Specializing in women’s history, she will work on earning her teaching credential. This is her first published work.