“Our Best but Not Our Only Customer”: Canada, Britain, and the Wartime Wheat Debate

Ashlin Daly

The onset of the Second World War threw the Canadian agricultural market into turmoil. The Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), still in its infancy, struggled to fulfill its purpose of regulating sales. The CWB had only come into being in 1935, just a few years prior to Britain’s declaration of war in 1939, as a voluntary marketing board to which farmers could sell their wheat (CWB Report for 1935–36). The war collided with outstanding conditions for wheat production in Canada, meaning that the CWB had a great deal of wheat to buy but little opportunity to sell it (CWB Report for 1942–43). Scarce storage facilities and dropping prices marked this period (CWB Report for 1940–41). In short, the war years were fraught with a wheat surplus in Canada, leading to a dramatic series of regulations and ensuing debates – particularly in regard to the impact on trade with Canada’s biggest wheat buyer, Great Britain. To follow the course of the market and ensuing debates, I consulted the CWB’s annual reports for each of these years along with Canadian and British newspaper articles that provide responses to their activities.

From its inception, the Board was intended to regulate the wheat market by managing surpluses. Part of this function was facilitating cooperation between Canada and its many importing countries, the most important being Britain. The board’s inaugural report for the 1935–36 crop year describes how they sent several representatives in advertising and research to the United Kingdom and continental Europe to gather information that would help them market wheat to bakers and consumers overseas. Clearly, Britain was designated the most effective outlet for their wheat surplus.

That same report also includes a policy statement by the Minister of Trade and Commerce, William Daum Euler. He insists, “It is not necessary to have and there will not be a ‘fire sale’ of Canadian wheat, but it will be for sale at competitive values and will not be held at exorbitant premiums over other wheats,” demonstrating that securing fair prices on wheat was another key part of the Board’s goals. Unfortunately, each of these functions – surplus management, price maintenance, and increasing British demand – were the very functions that war would soon only impede further.

The CWB’s 1938–39 report shows that in the war’s earliest days, the Board worked to strengthen its coordination with Britain. Firstly, they brought the European Commissioner to serve in a liaison role between Britain and Canada, improving communication just before the declaration of war. After the war commenced, In October 1940, the Board sent a delegation to England to discuss adapting to war conditions. A few positive outcomes in trade also shaped this brief period. For instance, in August 1939, just before the war broke out, “disturbing European events” caused prices and exports to surge. The Board organised some substantial exports to Britain, initially intended as reserve stores to remain in Canada, then exported them as the conflict developed overseas (CWB Report for 1939–40).

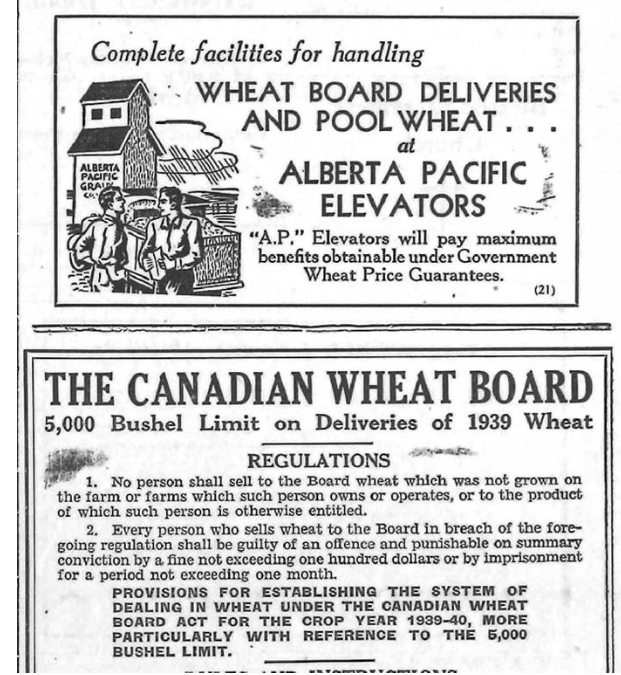

However, those early advantages did not improve the outlook for long. Reflecting on the 1939–40 crop season, the CWB reported, “It should be pointed out here that the position of the Board was not at all clear at this time.” Many policy changes had to be considered, not least of which was whether to close the futures market or leave it open (the Board favoured the latter, for the time being). They restricted production by limiting maximum wheat deliveries to 5,000 bushels, and breach was punishable by fine or imprisonment. In short, new developments in the 1939–40 crop season increased coordination with Britain and regulation on farmers.

Many non-farmers in Canada – namely, bureaucrats and executives – were preoccupied with Britain’s fortunes. To begin with, some expressed their belief that it was Canada’s patriotic duty to help feed Britain in wartime. A Hamilton Spectator article from 1939 describes Canada’s wheat surplus in a positive light, or a “blessing to the British Empire,” in the words of agriculture minister J. G. Gardiner. Additionally, The Winnipeg Tribune quotes the president of the Bank of Montreal, Huntly R. Drummond, in similar sentiments in a 1940 issue, asserting, “our great store of wheat is wealth in its best and most tangible form.” Both men were already anticipating that the current surplus would help feed Britain once the war was over, prioritising Britain’s future needs over Canada’s present difficulties. In these statements, economic inconvenience is recast as imperial virtue – evidence of Canada’s commitment to Britain’s wartime survival.

Not all public figures agreed on how best to manage that loyalty. Dr. Robert Manion, leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, was a vocal critic of the CWB’s wartime policies. Before war was declared, he was quoted in The Times with sentiments of loyalty in 1939: “If international gangsterism brought war it was Canada’s duty to show a united front and cooperate with the rest of the Commonwealth and other democracies.” However, by 1940, in The Winnipeg Free Press, he criticized the government for not “driving a harder bargain with the British Government” over wheat pricing.

This suggestion sparked fierce debate. Two days after Manion’s comments, The Winnipeg Free Press published an editorial criticizing Manion’s proposal. The failure of his plan, according to the article, is that a lower fixed price would cheat farmers, a higher fixed price would cheat Britain, and fixing a price solely for Britain would be unfair to the other importing countries. “Britain is our best but not our only customer,” it reminds readers, “We cannot afford to forget the others.” However, the article is also sympathetic to Britain, suggesting that enforcing higher prices amid its German U-boat blockade would be akin to blackmail. The long-term contracts and fixed prices Manion suggested were criticized as unfair to both Britain and Canada. While sympathetic, these arguments did not pledge Canada’s dedication to supplying Britain with the reverence of others.

In 1943, the CWB assumed monopoly status and began setting fixed wheat prices, which inspired even greater controversy. As The Canadian Statesman published, “Selling wheat through the wheat board has not got Canada any more for the wheat. As a matter of fact, there is pretty good reason to believe that selling wheat in the open market would have got us more for our wheat from Britain during the war than we have.” The essence of this argument is that if government-to-government sales were made a permanent arrangement for Canadian wheat sales to Britain, it would only make wheat cheaper for Britain, at a cost to Canadian farmers and taxpayers. “The Canadian farmer is not getting $1.25 per bushel for his wheat,” it contends, “He is getting that from the Canadian taxpayer who then sells the wheat to Britain at a lower figure.” Once again, the essence of debate is regulation versus free market, and which benefits Canadians versus Britons.

These debates reveal the growing unease among Canadians about whose interests the Board truly served. While some saw wheat sales as an expression of imperial solidarity, others viewed them as a mechanism through which Britain benefited disproportionately – with Canadian farmers bearing the cost. These archival sources demonstrate that wheat sat at the heart of wartime economic policy and imperial relations. From efforts to regulate prices and limit production to calls for imperial unity and criticisms of government overreach, the Canadian Wheat Board inspired great controversy. Even in a World War, questions of how much a farmer could get for a bushel of wheat and where to put it occupied contentious space in political and economic discourse.

Author bio: Ashlin Daly is a proud, lifelong Winnipegger and a fifth-year student at the University of Manitoba. She is graduating this spring with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours), majoring history and minoring in anthropology. In her final year, she also served as the president of the U of M’s History Students’ Association. Through her degree, she developed an interest in twentieth-century Canada, especially in the areas of social history and labour history.