Painting a Lie: The Myth of Spanish Exceptionalism

Alex Fischer

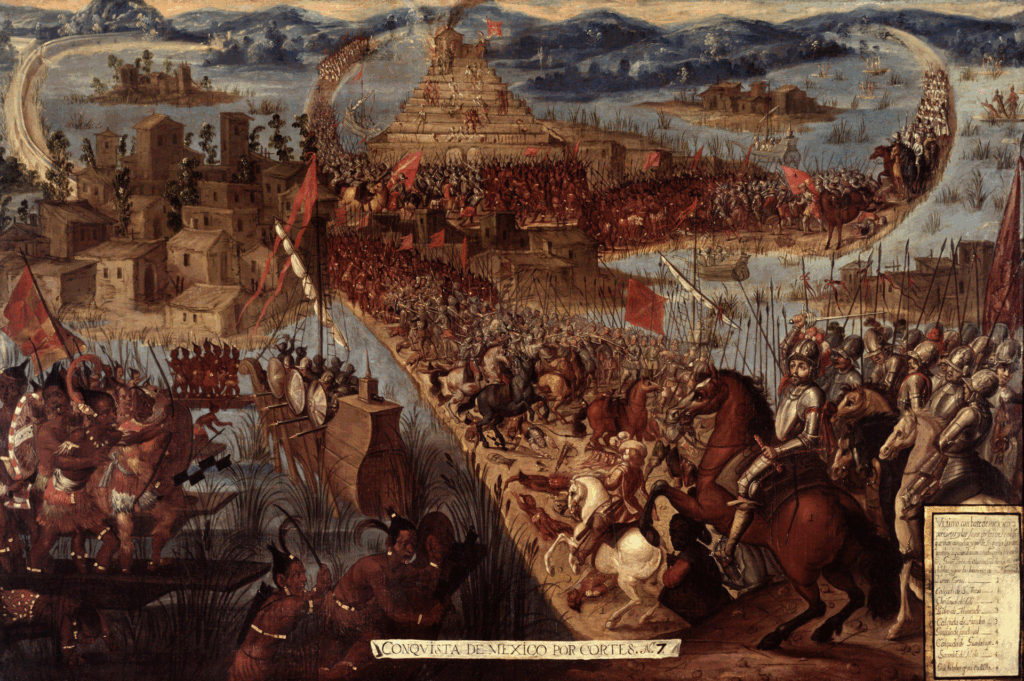

In the painting The Fall of Tenochtitlan (“Conquista de México por Cortés”), smoke rises in the distance as hundreds of Aztec and Spanish warriors clash on the causeways. Muscles tense, weapons flash, and a triumphant Hernán Cortés stands tall at the center, commanding both awe and victory. It looks like a battle between equals—a fair fight between civilizations. But look closer: something is missing. There is no disease, no despair, no trace of the thousands of Indigenous allies who helped bring the empire to its knees. The painting doesn’t just depict a moment in time. It constructs a myth.

Five hundred years ago, a small group of Spanish explorers traveled into a foreign empire. Alone and outnumbered by “hideous savages”, the men were all but doomed to be consumed by the “ravenous cannibals” around them. Yet, somehow, using only their wits, these men persevered. Their small group, only a few hundred in size, managed to conquer the “evil Aztec empire”, planting the Spanish flag atop the palace in Tenochtitlan as God smiled down upon them. These men were heroes who would go on to bring “freedom and civilization” to the Americas, and would be the pride of Spain for generations to come.

It was a story that felt impossible, divinely ordained, a true miracle upon the earth; that is the story of the Spanish conquest…at least according to the Spanish. Almost everything known about the conquest comes from the conquistadors’ accounts, and calling it biased would be an understatement. The Spanish crafted their story to make themselves appear exceptional, as light bringers of order unto the “New World of barbarians.” All of this was to secure as much fame and wealth as possible while also justifying the atrocities they had been “forced” to commit. And when this story reached the Spanish public, they loved it. Who wouldn’t want to celebrate the capture of a cannibalistic empire, or to share kinship with the courageous conquistadors? Spain turned Cortés and his men into national heroes, with statues and paintings made in their honor.

One such painting, The Fall of Tenochtitlan (“Conquista de México por Cortés”), shows the fall of the Aztec capital and the glory of Cortés and the conquistadors. But this painting, and the entire Spanish account of the conquest, has one problem: it’s a lie. The fall of Tenochtitlan was nothing like The Fall of Tenochtitlan. The painting doesn’t just depict a battle; it constructs a myth that erases the devastating role of disease and elevates Spanish heroism at the expense of the truth.

The Fall of Tenochtitlan displays a great battle being fought between the Aztecs and the Spanish. There are hundreds of warriors on each side, all of whom appear able-bodied and equal in stature. The only differences between the conquistadors and the native soldiers are their clothing and weaponry. While it is true that the Spanish had steel armor, guns, and horses the Aztecs lacked, the Spanish’s real advantage came from their resistance to Old World diseases.

Before the Spanish marched on Tenochtitlan, the Florentine Codex reports that “a great rash” broke out in the city, lasting sixty days. It says, “The Mexica warriors were greatly weakened by it. And when things were in this state, the Spaniards came.” Modern scholars have identified this “great rash” as smallpox, one of the most deadly diseases in the history of the world. In every part of Europe, Africa, and Asia, there are stories about smallpox decimating cities, killing off substantial percentages of their populations. And since smallpox came from the Old World, the Aztecs had never been exposed to it; they had no natural immunity or resistance like the Spanish did. As such, the Aztecs were annihilated. It’s estimated that eight million individuals in Mexico died of smallpox in the year 1520.

So when the Spanish began to siege Tenochtitlan in 1521, they were not fighting the fierce Aztec warriors who terrorized their enemies. They were fighting the sick, disabled, and anguished remains who had survived. In the last two months, these men had watched their children, wives, parents, siblings, friends, and neighbors die off one by one, as they barely escaped the same fate. This was not an inspired military force, well-organized and maintained. It was a few brave souls who still had enough strength to defend their way of life and whatever they had left. None of this appears in the painting. There are no sick warriors, no plague-stricken people, no sign of mass mourning. Instead, the image offers a clean fight, erasing the biological warfare the Spanish unknowingly carried into the Americas.

The painting’s portrayal of Spanish isolation is even more striking—just Cortés and his heroic band of brothers. In reality, they weren’t even alone. The Spanish did not win a glorious victory over an extremely strong opponent single-handedly. They weren’t even alone in battling the Aztecs, as they had allied with several neighboring states in a combined effort to capture Tenochtitlan. Being a militaristic empire that demanded tribute from its neighbors, the Aztecs had many enemies. Some of them, particularly Tlaxcala and Huexotzinco, eagerly joined the Spanish to vanquish their longtime tormentors.

These Indigenous allies provided not just moral support, but manpower. Tens of thousands fought, bled, and died in the campaign against the Mexica. They are entirely missing from The Fall of Tenochtitlan. Why? Including them would destroy the myth of Spanish exceptionalism and the foundation upon which the colonial structure was built. By including their allies in the painting, the Spanish would acknowledge their limitations and place these Indigenous individuals on equal footing. Furthermore, it would make the Aztecs appear superior to the Spanish by implying the might of the conquistadors was not enough on its own to capture Tenochtitlan. (The Spanish attempted to capture Tenochtitlan on their own in 1519. They managed to kill the emperor, Montezuma, but were otherwise defeated. The conflict is often referred to as “La Noche Triste” and is laid out in detail here).

If The Fall of Tenochtitlan wished to be an accurate recreation, many Aztec warriors would be sickly and covered in bumps. There would be boys taking up arms, not just trained soldiers. Thousands of Tlaxcalans and Huexotzincas would accompany the Spanish. But The Fall of Tenochtitlan doesn’t convey the truth of the conquest. It is a form of propaganda, preaching a narrative of Spanish exceptionalism and native savagery.

The painting misrepresents the past and participates in a broader campaign to shape historical memory. By controlling the past, the Spanish sought to justify their dominance and legitimize their rule, shaping how history remembers the conquest. This selective retelling glorifies their actions while downplaying the brutal realities of disease, exploitation, and indigenous resistance. In doing so, they ensure that their version of history endures, reinforcing a legacy of superiority rather than devastation and survival.

In 2015, Kathleen Ann Meyers published In the Shadows of Cortés: Conversations Along the Route of Conquest, analyzing interviews she had with locals as she traced the route Cortés took on his march toward what is now Mexico City. She found that some people still believed that Cortés was a genius and tactician whose individual brilliancy, combined with immense willpower, allowed him to topple an empire. These same individuals were convinced that Indigenous people five hundred years ago looked up to Cortés, believing him to be the god Quetzalcoatl. But this ideology is incredibly dangerous. Not only is it outright false, it erases the agency of indigenous peoples in their own history, reducing them to tribal warriors or naïve believers in a false god, and portraying the Spanish as some unstoppable force.

This version of history paints the Americas with Eurocentricity, as if everything before the arrival of Columbus was merely a prequel to the main story. It denies the existence of complex political relationships, unique cultural identities, and indigenous governments that thrived independently for centuries. This narrative, perpetuated by paintings like The Fall of Tenochtitlan, frames history with a colonial brush, flattening nuance and shadowing over entire civilizations. To see clearly, we must strip away these layers, reframe the composition, and allow indigenous perspectives to reclaim space on the canvas of history.

Author bio: Alex Fischer is a third-year student at UCSB, double majoring in History and Data Science. He spends much of his time working in the LEAF lab analyzing groundwater reserves in Pacific islands. Outside of school, his hobbies include playing spike ball, hiking, and weightlifting.