Reading Empire Through Ancient Eyes: What Xenophon’s Anabasis Reveals About Persian Power

Bridget Panina

Propaganda has existed in society long before you or I opened an article online or turned the television on to watch the news. Interpreting such propaganda gives insight into any time period’s political, cultural, and social context. One compelling example of historical propaganda is Xenophon’s ancient text, the Anabasis, which provides a detailed account of religion, royal ideology, and governmental and societal structures within the Achaemenid Persian Empire during a period of unrest.

Xenophon, a Greek exile, wrote the Anabasis in the mid-300s BCE. It documented a series of power shifts within the royal lineage surrounding Cyrus the Younger, a royal in the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The empire lasted from around 550 to 330 BCE, was founded by Cyrus the Great — not to be confused with Cyrus the Younger — and gained its power through conquest. In around 400 BCE, Cyrus failed to rebel against his brother, Artaxerxes, who was given the throne after their father, Darius, passed away. Xenophon, who supported Cyrus, completed the Anabasis roughly thirty years after these events after having joined Cyrus on his quest to oust his brother from power. While the exact date is unknown, the versions we read today are English translations of a Greek text that was likely published around 360 BCE, before Xenophon returned to Athens.

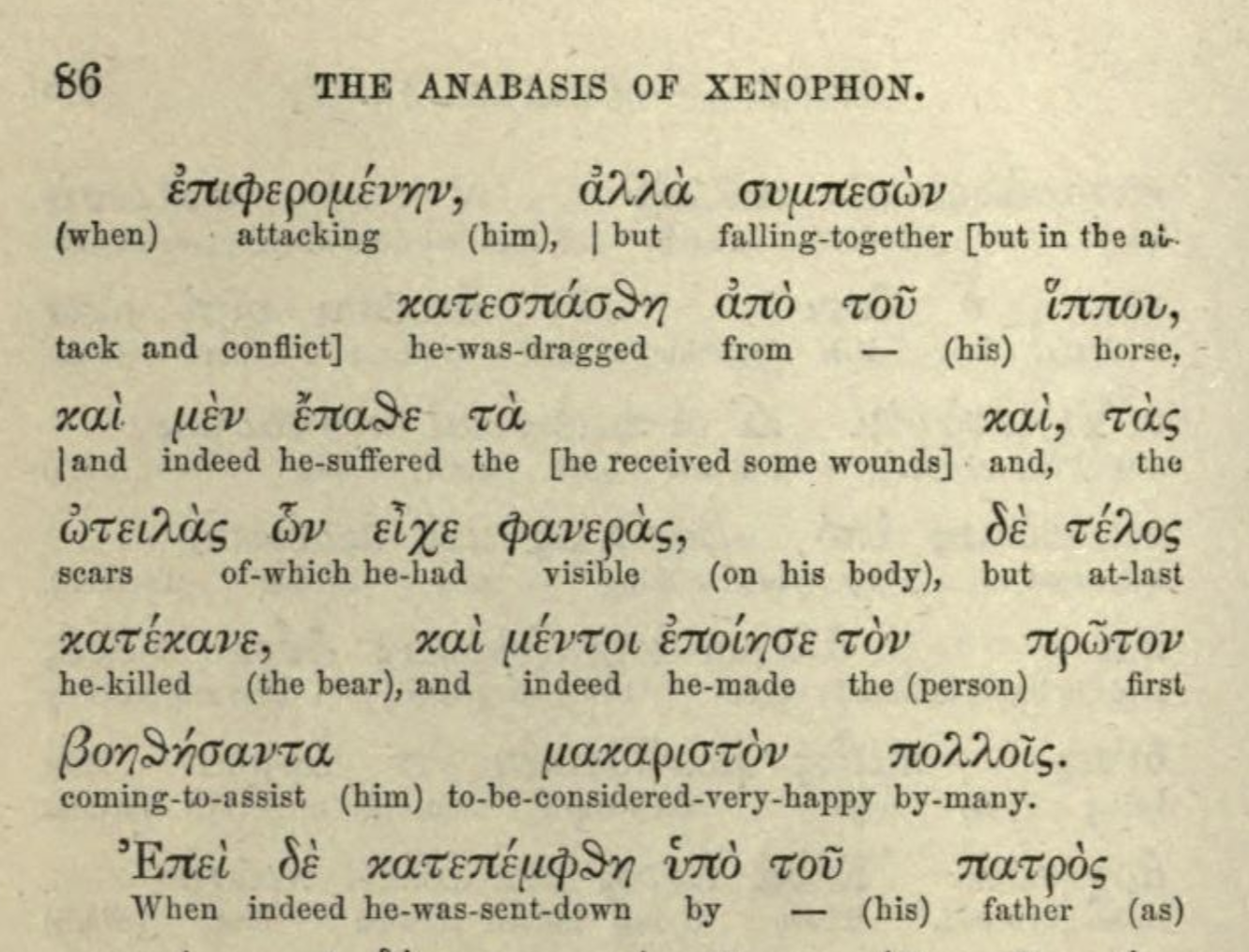

Since its original publication, it is impossible to say how many printings the original Anabasis has been through. The version I read was published in 1998 by the Loeb Classical Library, edited by John Dillery and translated into English from the original Greek by C. L. Brownson. Like other editions of the Anabasis, it includes an English and a Greek version. However, unlike one nineteenth-century interlinear edition alternating line-by-line between Greek and English, this late-twentieth-century version alternated every other page.

In the Anabasis, Xenophon reveals how religion was used as a tool for imperialism in the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus’s efforts to take the throne from his brother, Artaxerxes, included unbelievable feasts that had gained him the support of the gods. “After so doing, Cyrus proceeded to cross the river, and the rest of the army followed him, to the last man. And in the crossing no one was wetted above the breast by the water,” wrote Xenophon. “The people of Thapsacus,” he continued, “said that this river had never been passable on foot except at this time, but only by boats; and these Abrocomas had now burned, as he marched on ahead of Cyrus, in order to prevent him from crossing. It seemed, accordingly, that here was a divine intervention, and that the river had plainly retired before Cyrus because he was destined to be king.” Crossing a seemingly impassable river with divine intervention, Cyrus’s efforts to usurp the throne are framed as legitimate in the Anabasis, not just politically but spiritually. This use of the divine as a justification highlights how religion was infused into political decision-making, especially when it came to making war.

Xenophon’s Anabasis offers more than a narrative of military retreat—it also reveals the values that defined Persian kingship. In his portrayal of Cyrus and Artaxerxes, Xenophon explores royal ideology: the traits and behaviors that made someone worthy of power. While Artaxerxes becomes king by birthright, Cyrus wins widespread support because of his character. Xenophon emphasizes that Cyrus is loyal, just, intelligent, and perceptive; he “knew how to judge those who were faithful, devoted, and constant.” It is mentioned that even Artaxerxes and Cyrus’s own mother “loved him better than her son who was King”. He is personable and treats his allies as friends, earning their respect across many regions. These qualities, not lineage, mark him as a rightful ruler. In the world of the Anabasis, royal legitimacy is based not just on blood, but on how a leader acted toward others.

Cyrus’s generosity is key to his image in the Anabasis. He gives “gifts which are regarded at court” and pledges money to his allies, presenting himself as loyal and fair—qualities that fit the ideals of Persian kingship. Even after Cyrus’s death, Xenophon continued to praise him, calling him “a true man himself.” Through Cyrus’s actions, Xenophon offers readers a clear view of the good king in Achaemenid royal ideology.

This royal ideology also valued strength and bravery. Xenophon elevates Cyrus as a flawless model of kingship, and by doing so, ties his own repetition to an inflated figurehead. One vivid example comes in the story of the bear. “Then, when he was of suitable age, he was the fondest of hunting and, more than that, the fondest of incurring danger in his pursuit of wild animals. On one occasion, when a bear charged upon him, he did not take to flight, but grappled with her and was dragged from his horse; he received some injuries, the scars of which he retained, but in the end he killed the bear; and, furthermore, the man who was the first to come to his assistance he made an object of envy to many.” This dramatic retelling of events reflects how Xenophon emphasizes Cyrus’ physical courage to justify his allegiance. Such hyperbolic stories may raise questions about the reliability of Xenophon’s account and underscore the difficulty historians face in separating truth from flattery.

Xenophon also praised how Cyrus turned these qualities into political support, especially in his role as satrap of Lydia, a semi-autonomous province in the western reaches of the Achaemenid Empire. Although he was not king, the Anabasis shows that Cyrus could still govern his region with considerable independence. Xenophon also highlights how foreign regions provided troops and resources when needed. Many rulers allied with the empire lent parts of their military to Cyrus, with soldiers coming from Cilicia, Arcadia, Megara, and even Sparta. These areas were not Persian in culture or ethnicity, yet they still supported Cyrus’s campaign against his brother. By including this, Xenophon draws attention to a unique feature of the Persian imperial system: its ability to welcome outside allies while maintaining a clear sense of Persian identity and supremacy.

While the Anabasis has helped historians understand the structure and values of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, it also challenges readers to question the source’s credibility. Xenophon infused the text with elements of religion, royal ideology, and Persian societal structure to construct a stoic, heroic image of Cyrus and his army — an ironic ending for a man who ultimately failed in his effort to remove his brother from the throne. This characterization of Cyrus was far from neutral. Xenophon and his writing were profoundly shaped by a personal loyalty that, at times, makes this history read more like propaganda than impartial narrative.

By depicting Cyrus as the perfect ruler, Xenophon was also defending his choice to support a failed rebellion. In glorifying Cyrus, he attempts to redeem himself. This complicates the value of the Anabasis as a historical source, as it reveals as much about Xenophon as it does about the empire he described.

Author bio: Bridget Panina is a first-year History of Public Policy and Law student at UCSB. Originally from San Francisco, she leads tours for the Gaucho Tour Association, listens to podcasts, and roller skates around campus—that is, when she’s not reading history in the library.