2023 Stuart L. Bernath Prize Winner

Department of History, UC Santa Barbara

The Cherokee Nation of present-day Oklahoma adopted Euroamerican practices of slaveholding in the late eighteenth century to demonstrate to white Europeans that they were deserving of legitimate and respected citizenship in the United States. In the early 1800s, the Cherokee faced pressures to cede their lands, but even this became widely contested by anti-removalists. According to Mary Hershberger, “Most of the immediatist leaders in the 1830s…had also been anti-removalists at the turn of the decade.”[2] Though abolitionists’ main objective was to bring about the end of slavery, they also respected the Indigenous peoples living in North America and were active participants in the struggle for the rights of Indigenous tribes. This contradiction calls to question the political dispositions of anti-removalist abolitionists. How did Northern abolitionists reconcile their support of Cherokee Civil Rights with Cherokee slaveholding practices? Did abolitionists of the mid-1800s struggle with conflicting sentiments surrounding the slaveholding practices of the Cherokee? I have chosen to focus on Cherokee slaveholders because they were notorious–compared to the other Five Civilized Tribes– for the number of enslaved people they owned and the number of conflicting statements made by various historians regarding the treatment of their enslaved Black population. Though these disagreements may have made the research more difficult, they also made the work much more interesting, allowing me to come to a number of my own conflicting conclusions, just as the abolitionists of the time may have. Additionally, the scholarship concerning the Cherokee tribe was much more extensive than that of the Chickasaw or the Choctaw peoples. Focusing on the Cherokee allows historians to fully analyze the relationship between slavery, Indian Removal, and abolitionism.

Context of Cherokee Slavery

To put it simply, the Cherokee did participate in the institution of slavery. They were considered one of the Five Civilized Tribes due to their slaveholding practices along with the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole peoples. Initially, this was to receive positive recognition from their new colonial “guests” in North America; however, as time went on, the Cherokee Nation began to split into two factions, one considering the institution of slavery as a right to be enjoyed by the Cherokee, and the other declaring it a progressive scourge forced onto the people by the ‘White Man.’

Before Indigenous people adopted the Southern institution of slavery, there preexisted a system of slavery among the Cherokees based almost entirely on vengeance, having little to do with material wealth. According to Theda Perdue in Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540-1866, unfree people were called atsi nahsa’i, “one who is owned,” and were obtained almost entirely through warfare.[3] While their function is not entirely known, Perdue states that it is confirmed that “the Cherokees did not keep the atsi nahsa’i for economic reasons.”[4]

As white traders began to barter with Indigenous tribes for their slaves in the eighteenth century, said enslaved people “occupied an increasingly important position as a financial asset” for the Cherokee. Before long, “whites found African slaves to be a far more satisfactory labor supply than Indian war captives.”[5] These new preferences were most likely caused by the significant Indigenous population losses due to the rampant spread of disease from the incoming Europeans. To cater to the Europeans’ newfound favor of African labor, “The Cherokees discovered that the capture of black slaves was particularly profitable, and by the American Revolution most Cherokees traded almost exclusively in black slaves.”[6]

As programs developed in the 1790s to “civilize” the Indigenous peoples of North America, “Cherokees quickly adopted the white man’s farming implements and techniques, and those who had substantial capital to invest in agricultural enterprises soon came to need additional workers.”[7] Thus, the Cherokee began to practice the ownership and utilization of African slave labor, perceiving the subjugation of Black people to be in their self-interest and ultimately imitating the self-interest and greed of nineteenth-century capitalism.

As murmurs of Indian Removal grew ever louder, pro- and anti-removalist parties formed and began taking steps towards their respective goals. Around the same time, movements towards the abolition of slavery called into question the approval for or condemnation of the Five Civilized Tribes for their slaveholding practices. Hershberger states, “Opponents of removal believed that Americans had made an implicit promise to the Indians: If they adopted European agricultural practices, they would be granted the same rights and privileges as white settlers.”[8] The judgment of abolitionists towards the Cherokee was often kept to a minimum. While the reasons for this ranged, it is most likely that white abolitionists felt partially responsible for the Cherokee’s attitude towards slaveholding. The Cherokee Nation’s hand had been forced to be accepted into American society. Though these Indigenous peoples posed a threat to immediate abolitionism, Northerners could not possibly blame them completely. They believed slavery as an institution was a poison that infected Cherokee territory just as it did to the rest of the United States. Unlike white enslavers, who did so of their own volition, the Cherokee had transformed and adopted slavery to fit the standards of their colonial masters. Abolitionists recognized this and thus tried to reduce criticism and punishment towards Cherokee enslavers to a much lower degree than their Southern white counterparts.

Western Cherokees did not own a significant amount of enslaved people. However, according to Daniel F. Littlefield and Lonnie E. Underhill in “Slave ‘Revolt’ in the Cherokee Nation, 1842,” the Eastern Cherokees listed having 1,600 slaves in the census of 1835.[9] An article written ten years later in the Christian Watchman provides an estimate of the number of enslaved people in the Cherokee Nation as 2,000.[10] These two sources’ figures fill the gap between the numbers shown in Michael F. Doran’s “Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes,” which affirms that the Cherokee owned roughly 1,592 enslaved Africans in the 1830s and 2,511 in 1860.[11]

A Sliding Scale in Abolitionist Sentiments

In response to the specific practices within Cherokee slaveholder society, as well as the actual numbers of African bondsmen they owned, abolitionists began forming a variety of opinions and publishing them in their newspapers. Explicit and clearly stated approval and sympathy for and criticism of the Cherokee amongst abolitionists occurred on a sliding scale with a general “lack thereof” stance placed firmly in the middle. At different times, the Cherokee Nation was praised for their work in emancipation efforts and denounced for their participation in such a cruel and sinful institution as slavery. This assortment of abolitionist sentiments demonstrates an uncertainty within anti-slavery circles and an inability to come to one solid conclusion.

Approval and Sympathy

Some abolitionist and Quaker news publications demonstrate legitimate support for and approval of the Cherokee tribe. An article from the Philanthropist titled “WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE!” implies the collaboration between abolitionists at the Philanthropist and Cherokee. In this piece, author ‘Logan’ discusses the existence of a Cherokee anti-slavery society and that this society has come to the conclusion that it was, in fact, slavery, and not the Democrats or the Whigs, that was the root cause of the money issues in the 1840s.[12] This collaboration insinuates the approval of one group for the cause of the other and vice versa. The Cherokee’s critique of slavery is an introduction to Logan’s article, which itself is an expansion of the concepts discussed by the Cherokee anti-slavery society. Using their argument to develop his own further, Logan demonstrates an inherent appreciation of it, and their words inspire his piece.

These news publications often demonstrate sympathy for the plight of the Indigenous people, sorrow for the tradition lost to the institution of slavery, and objection to the tragedy that was the Indian Removal Act. The Friends’ Intelligencer demonstrates such sympathy in “THE CHEROKEE INDIANS,” stating, “[Chief John Ross] had watched the progress of his people from one stage of enlightenment to another, and never expected to see them reduced to their present suffering.”[13] By utilizing the first half of this statement, concerning the enlightenment of the Cherokee, the Friends’ Intelligencer displays a genuine belief in such knowledge and wisdom; the Indigenous peoples were intelligent and undoubtedly capable of societal growth. The latter half of the quote shows that the abolitionist writers at this publication were well aware of and wholly willing to acknowledge the suffering of the Cherokee people during this time of Removal. If these publications showed any lack of acknowledgement and demonstrated indifference, it would imply that the struggles of the Cherokee and other Indigenous peoples mattered little and could suggest much more harsh sentiments regarding their slaveholding practices.

Lack Thereof

There is strong evidence to suggest that most abolitionists were persuaded that the Cherokee were less to blame for their slaveholding practices; rather, that the institution of slavery had embedded itself into and poisoned Cherokee land. These accounts lack any of the sympathy or even spite displayed in other news publications. An untitled article from The Friend refers to the enslavement of Africans as a barbaric practice that “defiled” Indian Territory.[14] This language implies that the author did not believe the Cherokee people had much of a choice in the matter and that slavery had them firmly in its oppressive grasp. The Liberator expresses similar sentiments more explicitly, stating that “they [the Cherokee] are not so much to blame” for their slaveholding practices.[15] Abolitionist publications were keen on defending the name of the Cherokee Nation, whose subsistence-based economy before colonization did not need a surplus. Before the infiltration of Euroamerican slavery into Indigenous society, excess was useless and simply a sign of greed. The power that slavery held over the people was not so easily challenged; thus, the Cherokee people could not be entirely to blame for the practice. Abolitionists recognized the Cherokee and other Indigenous peoples as victims of the institution of slavery, albeit in a different way than enslaved Black people. The sentiments described in the newspapers above demonstrate an understanding by abolitionists that the Cherokee were forced to become dependent on the system to be accepted into American society.

That said, it can be argued that these sentiments do not “lack” sympathy but rather are laced with it. The notion that abolitionists did not wholly blame the Cherokee for integrating slavery into their society demonstrates a certain level of understanding, compassion, and overall sympathy for these Indigenous communities. Such reasoning aids the argument that abolitionist societies were more inclined to show support for the Cherokee tribe instead of condemning them.

Comparison with the South

It is likely abolitionists failed to judge Cherokee slaveholders so harshly due to preconceptions of Southern slave-owning practices. In his article, “Am I Not a Husband and a Father?,” Keith Michael Green writes, “Devoid of financial motives and familial separation, the alleged mildness of Native American slavery emphasizes white Southern slaveholders’ callousness towards black families.”[16] Abolitionist newspapers and propaganda were heavily focused on the cruelty of Southern whites towards their Black bondsmen. Images of the immense suffering of Black individuals and communities at the hands of Southern enslavers did well in garnering sympathy from potential allies of the abolitionist cause. Such imagery can be seen in the American Anti-Slavery Almanac; anti-slavery activists utilized a variety of illustrations depicting the selling, branding, and cutting of enslaved Africans to demonstrate the barbarity of Southern enslavers in the practice of their institution.[17] Such cruelty became the standard thought that came to mind when one thought of Southern slavery; thus, seeing anything less than barbaric would not bring much concern. The said “mildness” of Indigenous slaveholders may have prompted abolitionists to overlook them in favor of their more severe Southern counterparts. Critiques against Southern enslavement were often much more explicit, referring to specific slaveholders and pro-slavery sympathizers as barbaric and violent; such was the case in the Caning of Charles Sumner, in which Democrat Representative Preston Brooks used a walking stick to brutally beat the abolitionist Republican Senator Charles Sumner in May of 1856. Yet, no such slander is addressed towards Indigenous people. The abolitionists were willing to give Cherokee slaveholders a chance–some leeway–compared to Southern enslavers. A lack of criticism among abolitionists for Cherokee enslavers may have resulted directly from anti-slavery societies simply having bigger fish to fry.

Criticism

Most direct criticism of Cherokee slaveholding practices comes from Christian and Quaker news publications. An article from the Christian Watchman refers to the institution as a system whose principles are based on unrighteousness. The author discusses a steady increase in enslaved Africans within the Cherokee Nation and laments the fact, repeatedly denouncing the sin and moral evils that the practice embodies. “That slavery should exist at all among them is deeply to be regretted.”[18] This increase was indeed steady. Referring back to the section on the context of slavery among the Cherokee, utilizing Michael F. Doran’s data would show that there was a 57.73% total increase in the number of enslaved people owned within the Cherokee Nation from 1830 to 1860.[19] Some further math would demonstrate that there was a steady increase of approximately 25% from 1830-45 and 1845-60. (To be precise, the percent increase from 1830 to 1845 is 25.63%, and from 1845 to 1860 it is 25.55%.) Such a stable climb in the number of enslaved Africans among the Cherokee was sure to grant them criticism from Christians and Quakers. Moreover, abolitionists would surely have noticed the dramatic surge in enslaved people from 1830 to 1835, over 50% in just 5 years. This is likely to have been precisely what the Christian Watchman referred to in their article.

Efforts by Missionaries

Quakers, who granted substantial support in anti-removal efforts, were also highly influential in the abolitionist movement.[20] These Quakers were prone to supporting the rights of a group of people who also practiced the very institution they were trying to absolve. One Quaker woman, who had temporarily hosted Chief John Ross and his family during the removal crisis, asserted:

I remember well that evening and our talk about slavery, for then I first learned that the Cherokees held slaves. And I said that the love of right, and of justice, and humanity which made us feel any wrong done to the Indian, made us unwilling it should be done to the less powerful, and less capable African.[21]

As a result of such critiques from Quaker and Christian circles, more legitimate efforts to reach Cherokee slaveholders were started by missionaries, fueled by “growing pressure […] by New England abolitionists.”[22] In response, missionaries denied Cherokee slaveholders membership to missionary churches and actively preached against slavery during services. In William G. McLoughlin’s “Cherokee Slaveholders and Baptist Missionaries, 1845-1860,” he states that the Baptist Board of Foreign Missions’“fear of jeopardizing a highly successful missionary enterprise […] led them to act quietly and informally to purge the mission of all connection with slavery.”[23] The actions taken by these missionaries were some of the only ones explicitly taken by organizations sympathetic to abolitionism. This–in addition to the missionaries’ lack of severity towards Cherokee slaveholders – suggests that anti-slavery advocates were not as keen to condemn Indigenous peoples for the practice of the institution of slavery. Furthermore, according to Perdue, missionaries also stated that the Cherokees regarded slavery as “‘simply a political institution.’”[24] This declaration by Christian missionaries further demonstrates the apparently widely held belief among abolitionists that blame for the institution of slavery could only really be placed on the Europeans who brought it to North America; Indigenous peoples were victims of a certain caliber. Even the people most active in punishing Cherokee slaveholders demonstrated some leniency. Moreover, in 1849, “Out of 1,100 converts only five owned slaves.”[25] As a percentage, this is less than 0.5%; I imagine such a small figure would do little to concern missionary societies more than the standard.

Such criticism and–albeit lax–punishments from missionaries towards Cherokee slaveholders also calls to question who specifically was subject to these treatments. Doran asserts that

Major Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist missionary efforts were carried on in the Indian Territory before the Civil War. Their main emphasis was placed on reaching the full bloods, but important ancillary activity was devoted to vitalizing the Christianity of the mixed bloods and their slaves.[26]

These “missionary efforts” refer to the abolition of slavery through biblical teaching, of course. There are some interesting implications to the missionaries’ focus on full-blooded Cherokees over those of mixed race. Despite being notorious for their harsh treatment and statistically owning more enslaved people, mixed-race Cherokees were overlooked in favor of their full-blooded counterparts. This intrigues me, considering it was widely believed that mixed-blood masters were much harsher on their bondsmen than full-blooded Indigenous People were; if this truly was the case, why would missionaries not turn their attention towards mixed-race slaveholders? Mixed-race Cherokees were also much more likely to be of the pro-slavery persuasion. At the same time, their full-blooded–much more traditional–Cherokee counterparts made up the anti-slavery Keetowah faction, which will be discussed in detail in a subsequent section.

Such practices on the part of Christian and Quaker missionaries imply that it was the full-blooded Cherokee that needed to be “saved,” as opposed to their mixed-blood counterparts, despite being notorious for their harsh treatment towards enslaved Black people.

The Enigma John Ross

It is imperative to discuss the character and actions of Chief John Ross, one of the prime representatives of the Cherokee Nation during the Indian Removal Act and a major slaveholder among the Cherokee during this time. There is much debate and contradiction among historians over Chief Ross’ true sentiments regarding slavery. Similar confusion is reflected in several abolitionist news publications, which often go back and forth between calling Chief John Ross and the rest of the Cherokee as pro-slavery and anti-slavery. A similar sliding scale occurs here in Chief Ross’ policies as the abolitionists’ sentiments discussed previously.

An 1857 article from the Liberator, titled “TOMAHAWKING THE MISSIONARIES,” contains the statement of Chief Ross, a renowned slaveholder. Here, he demonstrates an adamance towards protecting the institution of slavery among Cherokee Indigenous People. Ross insinuates that slavery is a political privilege and right to be enjoyed by his tribe and that its “existence […] is sanctioned by [Cherokee] laws, and by the intercourse of the government of the United States.”[27] Chief Ross’ statement provides an excellent counterargument to the claim that Cherokee Indigenous people were victims caught under the thumb of the institution of slavery. Rather, they were willing participants in its practice. Writers at the Liberator respond facetiously, calling Chief Ross “parrot-like” in his assertion and sarcastically attributing slavery to that which is divine.

That said, the Chief demonstrated neutrality sentiments closer to the beginning of the Civil War. When the Confederacy reached out to the Cherokee people and proposed an alliance, Chief Ross responded, “Our country and institutions are our own,” and declared that the Cherokee tribe would remain neutral in this war.[28] Later still, abolitionists from the Friends’ Intelligencer demonstrated immense enthusiasm over the actions of Chief Ross following Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, wherein he freed several Blacks from Cherokee enslavement:

The proclamation of freedom made by our noble President, was at once obeyed by the Cherokees, and they manumitted slaves worth half a million dollars. John Ross liberated $50,000 worth, and another gentleman released negroes worth $100,000. The Cherokees stand forth as an anti-slavery people, and are entitled to the sympathy of every loyal citizen.[29]

This contradicts the idea that Chief Ross wanted to defend slavery rather than enforcing the notion that abolitionists viewed the Cherokee as allies in the struggle for emancipation. The Friends’ Intelligencer’s final claim uses patriotism to elicit sympathy for the Cherokee, referring to Americans as “loyal citizens” to persuade through flattery.

As time passed, the Cherokee Nation began to split into two factions, one considering the institution of slavery as a right to be enjoyed by the Cherokee and the other declaring it a progressive scourge forced onto the people by the White Man. The former faction called themselves the Knights of the Golden Circle, while the latter called themselves the Keetowahs. Perdue states that “Most of them were the Ross faction and opposed Slavery,” ‘them’ referring to the Cherokee as a whole.[30] Perdue’s statement implies that Chief Ross was a member of the Keetowah Cherokee Natives, aligning himself with the faction of Indigenous peoples opposed to slavery. Yet, on the same page, Perdue refers to this party as neutral on the issue of slavery.[31] Chief Ross, one of the chiefs who most strongly defended slavery, was also the representative figurehead for the faction of Cherokees who opposed slavery–or were perhaps neutral to it. Would the Cherokee’s neutrality evoke frustration among abolitionists? Ultimately, Chief Ross gave up on his neutrality, and the Cherokees subscribed to the Confederate cause.[32] I found little reaction from abolitionists regarding this occurrence. However, many Cherokee individuals refused to fight for the Confederacy, and “the majority […] continued to support Ross.”[33] This implies that the Cherokee may have had conflicting feelings over Chief Ross but continued to support his efforts as a leader and representative of the Cherokee people.

Contradictions to Consider

There are two contradictions to consider in researching abolitionist sentiments over Cherokee slaveholding practices. The first concerns the enforcement of education laws by Cherokee slaveholders on behalf of their Black bondsmen; the second involves the Cherokee’s general concern, or lack thereof, over fugitives who fled their plantations. In examining these inconsistencies, historians may more carefully understand the opinions of abolitionists and how these discrepancies would have affected their views.

Teaching the Enslaved

Perdue states that “the Cherokees did not enforce the laws prohibiting […] teaching slaves to read.”[34] This assertion expands on a concept mentioned earlier in her work, where she discusses a general lack of implementation of racial laws targeting enslaved Blacks by Cherokee slaveholders. She states, “Cherokee planters in the East rarely objected to their slaves receiving instruction and claimed that it made them better bondsmen…A few Cherokees permitted the children of their slaves to attend the regular mission schools along with their own children.”[35]

That said, according to several Work Progress Administration (WPA) Interviews conducted in Oklahoma, enslaved Black people under the ownership of Cherokee slaveholders more often did not know how to read or write. Five of these interviewees were enslaved people under Cherokee masters. Of the five, none knew how to read or write, yet all expressed awareness over legislation forbidding their masters from educating them. One participant stated, “the Cherokee folks was afraid to tell us about the letters and figgers because they have a law you go to jail and a big fine if you show a slave about the letters.”[36] This fear among the Cherokee, if the abolitionists were aware of it, may have led them not to cast such harsh judgment on slaveholders. They were simply following legislation, avoiding prison.

In the Case of a Fugitive

An even more explosive debate is over how concerned the Cherokee Nation would become in the case of a fugitive slave. According to Perdue, “The absence of advertisements for runaways in the Phoenix probably indicates that slaves did not become so dissatisfied that they ran away.”[37] Henry Bibb’s first-hand account, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, reflects Perdue’s notion that the Cherokee were not as distressed as their Southern counterparts when their bondsmen escaped. While considering his escape following his Cherokee enslaver’s death, Bibb writes, “it would be at least four or five days before they would make any stir in looking after me.”[38] Trusting his assumptions, Bibb leaves and can go to Cincinnati without being caught. His narrative does not indicate that Indigenous people sought him as he left Indian Territory. This could imply that the Cherokee did not care much; their labor force was high enough that one runaway could be easily replaced or that the labor itself was not strenuous enough to need that extra body to fulfill the work. This lack of urgency on the part of Indigenous people regarding runaway slaves could have been considered refreshing to abolitionists, who already had their hands full with Southern enslavers’ advertisements for fugitives.

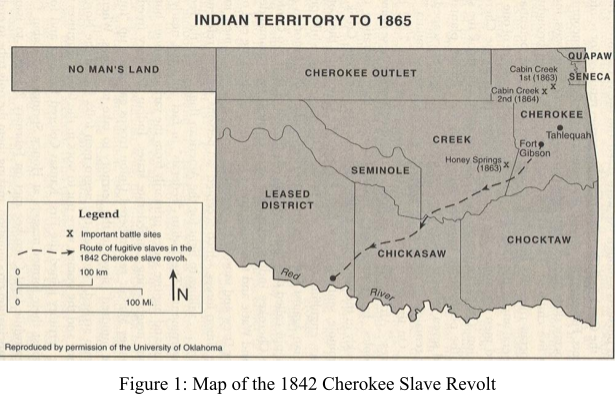

However, the events of the Cherokee Slave Revolt imply otherwise. In 1842, over twenty enslaved Africans escaped from their Cherokee plantations near Webbers Falls in the Cherokee Nation. Around three weeks later, they were captured approximately three hundred miles southwest of Fort Gibson (See Figure 1).[39] After the incident had been reported to the National Council of the Cherokees, one hundred “effective men” were commanded to pursue the fugitives.[40] For such a large number of men to spend a month traveling across an entire state to catch twenty enslaved people points to desperation on the part of the Cherokee to return these bondsmen to their enslavers. The lack of dissatisfaction that Perdue discusses in her work is ever present in the case of the Cherokee Slave Revolt of 1842. However, there is a chance it is not necessarily a contradiction and that the enforcement of Cherokee policy surrounding the capture and return of fugitive slaves occurred after Henry Bibb’s time as an enslaved person. Green states that Bibb was enslaved in Cherokee Territory in 1841, a year before the Revolt.[41] Littlefield and Underhill argue that “the Cherokee slave code had become more severe by the time of the Cherokee ‘revolt’ in 1842 than it had been before removal.”[42] They explained this severity as based on the fact that “The Cherokees accepted ‘the standards of neighboring white civilization,’ [and] ‘gradually adopted all the worst features of Southern black slave codes (including the mounted, armed patrols to enforce them).’”[43] It is likely that this increasing severity prompted this revolt and that it had not been so until around the time of or after Bibb’s escape. Such desperation to get these enslaved people back following the Cherokee Slave Revolt could have prompted abolitionists to view the Cherokee as harsh, going to great lengths to regain their property. Yet, according to Betty Robertson, they were not punished for their actions. At least, her father had not been, and he had belonged to Joseph Vann, considered one of the more harsh slaveholders among the Cherokee.

Vann owned most of the fugitives involved in the Cherokee Slave Revolt. Though I was unable to find any first-hand accounts of the Revolt, there does exist the account of the daughter of one of the fugitives involved exists. A WPA interview with Betty Robertson, whose father was one of the enslaved people who fled in the Cherokee slave revolt, makes no mention of her father receiving any punishment for his actions. She states that Vann kept Robertson’s father under his ownership following the ordeal and made him work harder.[44] That said, the number of fugitive slaves in this case was much larger than in Bibb’s narrative; such a large loss of “property” was bound to warrant concern among Cherokee enslavers.

Conclusion

While maintaining goals to eliminate the Southern institution of slavery, abolitionists continued to respect the rights of the previously established tribes of Indigenous people, notably coming to their defense during the conflict over Indian Removal. Despite the ever-increasing number of enslaved Black people within the Cherokee Nation, anti-slavery activists were not keen to slander the name of their Indigenous neighbors. How did Northern abolitionists reconcile their support of Cherokee Civil Rights with Cherokee slaveholding practices?

I do not believe anyone could come to one legitimate conclusion. Amid the Indian Removal Act and the impending threat of a Civil War, confusion ran rampant. It comes with little surprise that such uncertainty is present and reflected in various anti-slavery newspapers. However, there is much evidence to suggest that most abolitionists were sympathetic towards the Cherokee and held beliefs that they were more victims of the institution of slavery than perpetrators of it. Though explicit criticism of their practices was present in some abolitionist publications, this was often laced with pity for the loss of the Cherokee tradition.

An expansion of my work would do best to find more publications sharing opinions on this topic, including many more statements from Cherokee newspapers such as The Cherokee Advocate and The Cherokee Messenger. Furthermore, it may be interesting to investigate further the sentiments from pro-slavery advocates and news publications. Though anti-removalists and anti-slavery activists were often cut from the same cloth, the same may not be said for the other parties.

Appendix

Momodu, Samuel. “The Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation (1842)” Black Past, February 1, 2022. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/slave-revolt-cherokee-nation-1842/.

© 2023 The UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History

[1] Elayna Maquinales is a graduating senior (2024) at UC Santa Barbara with a major in History and a minor in Museum Studies. The following paper was also awarded the Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Research in June of 2023.

[2]Mary Hershberger, “Mobilizing Women, Anticipating Abolition: The Struggle against Indian Removal in the 1830s.” The Journal of American History 86, no. 1 (1999): 15–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/2567405, p. 35.

[3] Perdue, Theda. Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540-1866. 1st ed. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979, p.5.

[4] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p. 12.

[5] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p. 35.

[6] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p. 38.

[7] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p. 50.

[8] Hershberger, “Mobilizing Women, Anticipating Abolition,” p.20.

[9] Littlefield, Daniel F., and Lonnie E. Underhill. “Slave ‘Revolt’ in the Cherokee Nation, 1842.” American Indian Quarterly 3, no. 2 (1977): 121–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184177, p. 124.

[10] “Foreign Missions and Slavery.” Christian Watchman (1819-1848), Sep 19, 1845, p. 150, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/foreign-missions-slavery/docview/127222207/se-2.

[11] Doran, Michael F. “Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 68, no. 3 (1978): 335–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2561972, pp. 346-347.

[12] Logan. “WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE!” Philanthropist (1836-1843), Aug 11, 1840, p. 1, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/what-is-difference/docview/89825841/se-2.

[13] “THE CHEROKEE INDIANS.” 1864. Friends’ Intelligencer (1853-1910), Apr 23, p. 110, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/cherokee-indians/docview/91189336/se-2.

[14] “Article 7 — no Title.” 1828. The Friend; a Religious and Literary Journal (1827-1906), Jan 12, p.99. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/article-7-no-title/docview/91285198/se-2.

[15] “REFUGE OF OPPRESSION.: INDIANS AND ABOLITIONISTS. AN ACT FOR THE PROTECTION OF SLAVERY IN THE CHEROKEE NATION.” Liberator (1831-1865), Feb 01, 1856. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/refuge-oppression/docview/91209771/se-2.

[16] Green, Keith Michael. “Am I Not a Husband and a Father? Re-Membering Black Masculinity, Slave Incarceration, and Cherokee Slavery in ‘The Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave.’” MELUS 39, no. 4 (2014): 23–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24569930, p.39.

[17] American Anti-Slavery Almanac. Illustrations of the American anti-slavery almanac for . New York, New York. New York, 1840. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.24800100/.

[18] “Foreign Missions and Slavery.” Christian Watchman (1819-1848), Sep 19, 1845, p.150, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/foreign-missions-slavery/docview/127222207/se-2.

[19] Doran, “Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes,” pp.346-347.

[20] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.68.

[21] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.68.

[22] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.120.

[23] McLoughlin, William G. “Cherokee Slaveholders and Baptist Missionaries, 1845-1860.” The Historian (Kingston) 45, no. 2 (1983): 147–166. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24445785?seq=2, p.148.

[24] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.122.

[25] McLoughlin, “Cherokee Slaveholders and Baptist Missionaries,” p.151.

[26] Doran, “Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes,” pp.344-345.

[27] TOMAHAWKING THE MISSIONARIES. Liberator (1831-1865), Jan 02, 1857. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/tomahawking-missionaries/docview/91180351/se-2.

[28] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.127.

[29]THE CHEROKEE INDIANS. 1864. Friends’ Intelligencer (1853-1910), Apr 23, p.110. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/cherokee-indians/docview/91189336/se-2.

[30] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, pp.130-131.

[31] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.131.

[32] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.134.

[33] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.137.

[34] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.98.

[35] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, pp.88-89.

[36] Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 13, Oklahoma, Adams-Young. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn130/, p.268.

[37] Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, p.99.

[38] “Henry Bibb, 1815-1854. Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, Written by Himself.” n.d. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/bibb/bibb.html, p.155.

[39] Momodu, Samuel. “The Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation (1842)” Black Past, February 1, 2022. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/slave-revolt-cherokee-nation-1842/.

[40] Littlefield et al., “Slave ‘Revolt’ in the Cherokee Nation,” p.122.

[41] Green, “Am I Not a Husband and a Father?,” p.36.

[42] Littlefield et al., “Slave ‘Revolt’ in the Cherokee Nation,” p.123.

[43] Littlefield et al., “Slave ‘Revolt’ in the Cherokee Nation,” p.123.

[44] Federal Writers’ Project, pp.267-268.