PDF Version[1]

California and Climate Change

Climate change refers to long-term shifts in Earth’s climate caused by human activities. It leads to rising temperatures, altered weather patterns, and environmental disruption. Drought conditions have been exacerbated due to rapid climate change, resulting in an increasingly pronounced impact on California’s water resources. With water becoming a more scarce commodity, many have begun purchasing water rights. Among them are large Agribusinesses, which consume eighty percent of California’s annual water usage, or 34 million acre/feet of water.[2] Private ownership and the adoption of riparian rights during the mid-eighteenth century led to water privatization. This practice resulted in the ownership of vast tracts of land by large businesses that sought to monopolize water.

This article explores the San Joaquin Valley, particularly the Tulare Basin and the rivers that once fed into Tulare Lake, to understand how large agribusinesses came to dominate the valley and how they morphed state law into what we see today. Specifically, the historical development of the riparian rights system and its implications for the current water management situation are well shown. In particular, the socio-political and economic factors that facilitated the concentration of water ownership in the hands of just a few are laid bare. Overall, this paper seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the history behind the state of water management in the San Joaquin Valley, with a focus on the Tulare Basin, to shed light on the power dynamics that have shaped water distribution in California.

Tulare Basin and its Indigenous History

Formed by High Sierra runoff, Tulare Lake was an 800-mile inland lake that stretched across the desert valley floor of the San Joaquin Valley.[3] A thick fog would often envelop the area, mixing with gasses of the rotting tule in the thick clay marshes and creating a foul odor that became synonymous with the region. The edges of the lake would often grow and recede, leaving behind marshes. The lake was about 40 feet at its deepest point, with most of it being shallower at two to three feet deep.[4] This variation of depth levels lies in part within the area’s climate and whether or not it’s suffering through a drought. George Horatio Derby, an army topographer, describes Tulare Lake as the following in his 1860 survey:

The most miserable country that I ever held. The site was not only of the most wretched description, dry, powdery, and decomposed, but was everywhere burrowed by gophers and a small animal resembling a house rat. With the exception of a strip of fertile land upon the river emptying into the lake, it is better a desert.[5]

When not suffering from a drought, the lake would regain its whole expanse. The barren desert would transform into rolling hills, creating a vibrant landscape of indigenous flowers that enveloped the land in a prism of color. John Muir, a naturalist who migrated from Wisconsin to study the area, described the valley as “one smooth, continuous bed of honey-bloom, so marvelously rich that, in walking from one end to the other, a distance of more than 400 miles, your foot would press about a hundred flowers at every step.”[6] The valley’s beauty was laid magnanimously bare to him, with the rivers that fed into the lake lined with oak trees that faded into the horizon of the pine and redwood-infested Sierra Nevada Mountain range. Derby and Muir vividly portrayed the valley, illustrating its vulnerability to extreme conditions and its immense potential for cultivation.

The Yokut Tribe, the Indigenous inhabitants of the valley, were historically organized into numerous tribelets, which were, in turn, estimated to be around fifty in number. Each tribelet possessed a unique dialect, territory, and name.[7] They lived along the ten-foot-high tule reeds that surrounded Tule Lake. The Indigenous populations relied on the lake for its abundance of fish, which they caught bare-handed or with spears. The lake’s fish population included rainbow trout, pike, sturgeon, salmon, and other foods that provided enough sustenance to feed everyone multiple times over. Their fishing method was unique, as they used a large, buoyant raft capable of holding a family and hundreds of pounds of fish for many days.[8] During midsummer, the Yokut and Miwoks gathered to eat wild grapes and blackberries on the banks of the rivers that fed into the lake, making for a noisy and tight-packed gathering.[9]

In 1804, Father Juan Martin from Mission San Miguel Arcangel documented his travel inland and his interaction with the Yokut villages on the southeastern shore of the lake.[10] He observed beehive-shaped structures made from dried willow poles and tule, all lined up with a single large roof that extended over all the row houses.[11] The Indigenous population in the area was estimated to be roughly 30,000 when the Spanish began planning a new mission at the lake. The Spanish recognized the area’s potential for abundant agriculture and wealth, especially with the use of slave labor of converted neophytes.

Due to its rugged terrain and inhospitable environment, the valley was a refuge for fleeing “gentiles and bandits” from the coastal mission systems. Moreover, the “foothill natives” living on the mountain range were hostile towards the Spanish and, later, the Americans. These factors collectively made the construction of a mission system a challenging feat. Joaquin de Arrillaga, a Spanish aristocrat who governed California between 1800-1814, received appeals from Father Martin to construct a mission at the willing village of Bubal, which Martin had previously documented as having hive-like structures. However, Arrillaga instead established “civilizing squads” composed of a padre and a lieutenant. They were tasked with finding new village locations for the mission and converting the Indigenous peoples. Despite the existence of over twenty-four villages with a population of more than 5,000, no converts were made, and few children were born due to syphilis outbreaks that left many sterile.[12] Friars wrote to Arrillaga that the presence of the lieutenants instilled fear in the Indigenous peoples, causing them to view the Spanish troops as a threat to their liberty. As a result, no new mission was constructed. In 1805, a punitive expedition was launched to execute resisting neophytes.[13]

During the first half of the nineteenth century, there was a rise in aggression towards Indigenous populations as the Spanish empire shrank and Mexican influence waned, causing settlers from the west to increase. The murder of John Wood was a pivotal event that contributed to this. In 1850, when settlers along the Kaweah River were murdered, they began to clear fields and fell oak trees to build homes. Chief Francisco gave Woods and the settlers an ultimatum to remove themselves within eleven days, but the settlers refused to leave even when the deadline had passed. A Yokut band of warriors killed ten settlers in retaliation. John Wood managed to arm and barricade himself in the nearby cabin that was recently constructed, killing seven attackers before they broke down the door and dragged him to a nearby tree, where they began to skin him. His body was later found in the bed of the river.[14] The massacre, which occurred on 21 January 1851, prompted Governor John McDougal to send a special brigade to quell the Indigenous uprising, with two community leaders spearheading the campaign for peace.

Walter Harvey, the local judge, and James Savage, a linguist fluent in Indigenous and European languages, were notable figures in the region during the nineteenth century. Savage earned his fortune during the California Gold Rush, creating trade networks and goldmines. He eventually became the chief of many tribes, taking five wives and employing their relatives in his mine. Annie R. Mitchell describes how Savage treated the Indigenous population after receiving the nickname El Ray Huero, or “Blonde King,” saying, “This title had a peculiar effect on Savage. His latent leadership developed with ruthless intensity. His wish became command. They had the choice of resisting or perishing. They turned to savage for help, but he was only interested in gold.”[15] An attack at one of the trading outposts left his stores empty and three clerks mutilated following the Woods Massacre. From the perspective of the Indigenous, the continuous encroachment of Indigenous land by white settlers made it inevitable for conflict to occur. The stealing of land and resources, as well as the use of cheap labor, fostered Indigenous resentment, leading to an increasing level of rebellious attitude towards the settlers.

The violent attacks during this period forced the remaining friendly tribes residing on the lake to flee into the mountains and join the Indigenous people already in rebellion. After several months, Jim Savage led a battalion of seventy-five men with whom he killed “scores” of Indigenous and burned down several encampments. Upon returning from their expedition, they obtained nineteen signatures and secured a meeting with 120 bands of Indigenous peoples to negotiate appeasement. One of the significant stipulations of said appeasement was that 7% of the land along the Kings River and Tulare Lake would go to the Indigenous tribes, equivalent to roughly 900,000 acres.[16] However, this provision proved a mere formality since the land sat in the path of Western settlers who paid no attention to such treaties.

Despite the peace agreement, the United States government refused to recognize the treaty. This was made official through a historical note dated 30 May that stated “all territory not rewarded by said treaties”[17] would be open for settlement. On 13 May 1851, Despite Chief Francisco signing the treaty over half a month earlier, the lands of his and many other tribes fell under US jurisdiction.[18] In her doctoral thesis, Kumiko Noguchi writes about the erasure of the Yokut identity and the transformation of the social image of the Yokut tribes into the “Tule River Native.” She notes that “the treaty was initially ‘negotiated’ between tribes and agents but not protected by the federal government. Instead, the Indigenous peoples were forcefully removed from their ancestral lands.”[19] The goal of this forceful removal was not appeasement with all Indigenous people in the valley and surrounding area. G. W. Barbour was the US Commissioner appointed by President Fillmore, who wanted a quick solution to the Indigenous uprising and oversaw the treaty signings in the area. Noguchi writes,

The friendliest tribes, as Barbour recalled, were four Yokuts groups; Chunut, Wowol, Yowlumne, and Koyeti. The Yokuts around the area of Four Creeks had different attitudes toward the federal government from the Kings River Yokuts…they expected that the “Great Father” would protect their territory and food once the treaty was made[20]

The consequences of the Foothill Yokuts’ experiences had a ripple effect on the peaceful bands residing near Tule Lake. Surprisingly, the Chunuts and other lake tribes welcomed the US presence, at least compared to the Spanish. Nevertheless, on 3 June 1851, tribal leaders from the region signed 4 KAPP 1099, or the “Treaty with the Chunut, Wowol, etc.” at Paint Creek. Under the third article of the treaty,

To the Chu-nute and Wo-wol tribes, all that district of country lying between the head of the Tulare or Tache Lake and Kern or Buena Vista lake…the said tribes of Indians jointly and severally forever quit claims to the government of the United States to any and all lands to which they or either of them now or may ever have had any claim or title whatsoever.[21]

Despite the US Senate holding a “secret session” where all 37 senators voted against ratifying 18 treaties, much of the land would still be taken, and the new settler and mining populations would force out the population.

Yoimut, depicted in Figure 1, is believed to be the last full-blooded Yokut of the Chunut tribe. Fluent in eight Indigenous dialects as well as English and Spanish, Yoimut grew up on the eastern shore of Tulare Lake, where she witnessed the destruction of oak forests and the extermination of the elk.[22] One story recounted by Yoimut is that of a forced migration over fourteen days and eighty-five miles to the Fresno River Reservation, during which Indigenous people were whipped.[23] Yoimut’s mother personally witnessed twenty-two Indigenous people be killed by exhaustion or cruelly murdered by soldiers, often being trampled by their horses or stabbed by their swords. Four babies were born during the journey. According to Noguchi, “the treaty established two separate reservations on Yokut lands where four Yokuts groups were living.”[24] One of these was the Fresno River Reservation, where Yoimut’s mother was headed. This reservation collapsed in 1860 due to settlers encroaching on the land and violent conflict with the Indigenous, leading them to either flee to the Tulare Reservation or work for the new white settlers who had successfully claimed the lakebed. Consequently, many of the remaining Indigenous dispersed and began to work as laborers and domestic servants for the dominant white agricultural class, which was spurred by the prospect of gold along the numerous rivers and creeks.[25]

The Gold Rush and California’s Water

On 24 January 1848, the discovery of gold near Coloma by James W. Marshall served as the spark of the California Gold Rush. Within a month, the conclusion of the Mexican-American War led to a surge of soldiers migrating further westward, making them the initial prospectors to settle the land. Among the riches available to them was water. Hydraulic mining quickly emerged as a popular method for extracting gold. This mining technique involved transporting vast amounts of water to areas such as the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, where it would be highly pressurized and shot out of large cannons aimed towards cliff faces to wash away loose soil and debris to uncover gold. The environmental damage caused by this practice was severe. In addition to washing away cliffs, the runoff water caused flooding, carrying loose sediment from once towering cliffs onto farms and damaging soil composition and drainage.

Water thus became a vital component of industry, which led to an inevitable escalation of the privatization of water and its legal status. Before the emergence of any governing body in California, miners adopted both appropriative and riparian rights regarding privatization. Appropriative rights allowed individuals to claim any unclaimed water. Those who began to utilize the natural water were also entitled to divert and diminish its flow. This practice is predominantly employed by state and federal water organizations today. In California, during the gold rush, however, it applied to the numerous miners and farmers who settled on federal land. In contrast, riparian rights entailed the privatization of the natural water source, thereby transforming communal water into a private venture that was often sold to others who lacked a water source.

In his book “The King of California,” Mark Arax asserts that riparian rights were adopted in California in 1850 from English common law, which dictated that water flow would belong to those who owned the land. However, this law assumed that there was enough rainfall to support those who were not near a stream. This was not the case in California. The miners, recognizing the issue, adopted appropriative rights in practice while still acknowledging riparian rights, even though there was no legal precedent on the conflict between the two at the time. Meanwhile, on the East Coast of the United States, a different approach was taken to this issue. In the article “Water Rights in the Western States,” Samuel C. W wrote, “Riparian rights stemmed not from English common law, as is generally assumed, but were borrowed by American jurists and treaty writers. They were first introduced to American law in the 1820s by Justices Joseph Story and James Kent. By 1849, English jurists had accepted riparian rights and specifically cited Story and Kent as their authorities. It was this concept of riparian rights that eastern states adopted, and that confronted the western practice of prior appropriation.”[26]

American jurists laid the legislative foundation of common law for the English. This confrontation led to confusion in California, with many abusing the interpretation of the law and adversely affecting small miners and farmers. In his work, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush: Conflicts over Economic Points of View,” Douglas R. Littlefield examines several lawsuits involving mining and water companies, which forced Californian legislatures to create a new system of water regulation that would grow to influence other western states and begin forging a path towards the privatization of water. Littlefield’s research differs from others in that he analyzes his sources from an economic perspective and examines how that played a role in the manufacturing of this new regulatory system.

In the early 1850s, petty disagreements among miners and farmers began to emerge, with some entrepreneurial individuals claiming that water was a commodity and could be sold. This created a rift between those in favor of riparian versus appropriative rights. Those in favor of appropriative rights argued that water is an innate right given to the people in the area, allowing free use by all, including miners. Others supported riparian rights, hoping to successfully turn water into a commodity that could be sold to miners who increasingly needed more due to the growth in the mining and agricultural sectors. Littlefield notes that the prior usage of appropriative rights fit well in California due to its tendency for drought. Those who supported riparian rights emerged years later with the arrival of entrepreneurial individuals into the valley, showcasing “an antagonism between individual enterprise and a capitalist, corporate ethic.”[27]

In his analysis of water rights in California, Littlefield writes: “In 1853, legal cases regarding water usage began to emerge and reach the California State Supreme Court. Despite the court’s formal declaration of prior appropriation as the legal means of acquiring water rights in 1855, the economic question of water’s marketability remained unresolved.” However, the federal government’s acquisition of California and the discovery of gold complicated matters, making it difficult to determine land ownership. Additionally, with the looming Civil War, discussions about water legislation were not a priority. Littlefield also notes that the California Practice Act acknowledged “customs, usages or regulations established and in force at the bar, or diggings” as the formal basis for settling disputes in mining areas. Although this law did not target water issues directly, miners perceived it as justifying both riparian and appropriative rights depending on whichever benefited them more.[28] California did not explicitly address water rights in its legislation, but the intention behind the law was evident, resulting in both appropriative and riparian rights being recognized without formal sanctioning.

River mining companies commonly employ “L-shaped” structures to divert a portion of the river’s flow, exposing banks where gold could be sifted out. However, this practice often led to conflicts as it caused flooding of both natural wildland and agricultural fields, particularly between cooperative companies and the more corporate-oriented mining operations. Cooperative prospects collaborated in constructing some of the earliest ditches and canals to divert water for sifting dirt laden with gold dust. These canals were typically no deeper or wider than one to two feet, unlike larger canals funded by urban investors. The primary source of profit for these ditches and canals was derived from gold, though excess water was also sold to other prospects.

Many of these cooperative waterways were eventually sold for a fraction of their cost, often to large creditors in cities such as San Francisco and Sacramento. The rationale behind these sales was rising maintenance costs, which outpaced the declining income from gold and water. These new creditors viewed water as a commodity rather than a resource and involved themselves more in the selling of water to miners than mining. This resulted in the separation between water and its association with mining for gold, which in turn became an entirely new enterprise. Many miners began to push back against these creditors because water was a basic right, spurring strikes against these new water companies. One strike occurred at Iowa Hill in Placer County against the Tuolumne County Water Company, with locals referring to them as a “monster monopoly” and a “bloated corporation.”[29] Momentum grew for the Stanislaus River Water Company, a competitor against Tuolumne, with locals depositing their money into banks funding the project while closing accounts with those funding the Tuolumne project. Many people volunteered to work for free to build the new canal, and the Stanislaus Water Company opened in 1858. Sadly, with continued legal battles from the Tuolumne Water Company and the increasing costs for materials and maintenance, the company was sold for one-third of the original cost to their rival, Tuolumne, further increasing disdain against emerging water monopolists.

The growing division between miners and water companies led to a surge in litigation as the federal government and state legislature remained indifferent to the matter. Without a formal regulatory framework, local judges were often called upon to adjudicate disputes. Before litigation, local miners’ committees attempted to settle water cases through arbitration but tended to exhibit a bias towards free water use. Similarly, local judges tended to favor local miners in most cases, displaying a preference for their interests over those of larger water companies. For instance, in the district court trial of Priest v. Union Canal Company (1855), the judge instructed the jury that each case relied on its “peculiar” circumstances. The jury ruled in favor of D. Q. Priest and his co-plaintiff, the North Shirt Tail Ditch Company, a small-scale water project catering to local miners. Although this outcome reaffirmed the appropriative rights of the plaintiffs, the judge’s phrasing indicated that riparian rights could still be recognized under certain circumstances.[30]

In Hoffman v. Stone (1857), the California Supreme Court echoed this sentiment when Justice Hugh Murray stated that water rights were “based upon the wants of the community and the peculiar conditions of things in this state, for which there is no precedent, rather than any absolute law governing such case.” In the years following, however, the Supreme Court of California heard two cases that effectively changed how water was legislated and separated it from its association with mining, enshrining it as its own independent enterprise.

The first case, Eddy v. Simpson (1851), had significant implications for water rights legislation in California as it involved the application of riparian rights to water that had been abandoned. A.H. Eddy and the Shady Creek Company had built a dam and ditch to sell water to local mining companies. At the same time, John Simpson and his investors had cooperatively diverted water from Shady Creek to feed their mining operation. The Grizzly Company, which Simpson and his investors owned, subsequently dammed up Shady Creek, putting Eddy and the Shady Creek Company out of business. The ruling in favor of Shady Creek was based primarily on common law and ignored the economic conflicts between mining and water. While neither company owned the land required to divert water through riparian rights, the judges affirmed riparian rights by defining abandoned water, giving riparian rights greater legal validity. Despite the ruling, it was clear that water had become a commodity, with the sale of water being a primary concern for the Shady Creek Company and mining being the primary concern for the Grizzly Company.

The second case, Irwin v. Phillips (1855), involved Mathew W. Irwin, who diverted water to his own mining venture in Eureka in 1851. He dammed Poor Man’s Creek the following year. Robert Phillips and his partners, collectively referred to as Bradie and Company, cut his dam based on the argument that the waters behind the dam covered their claim. Furthermore, they asserted their right to undiminished natural water flow under riparian rights.

In response to the formal complaint, Bradie and Company stated that local custom and consent permitted stream waters “only to be disturbed and removed by those mining along the margin of that stream. While this sounds like riparianism, nowhere did Bradie and Company mention property ownership – a central principle of riparianism – as a condition for water.[31]

Littlefield explains here that the prior acceptance of appropriative rights resulted in those who accessed the water flow first gaining primary access. This reaffirmed water’s independence from mining, with Irwin making a substantial amount of money by selling water to local miners. The court sided with Irwin, citing prior appropriative rights through “priority of location and appropriation.” Although this was a setback for riparian rights, Bradie and Company did not specifically mention property ownership, so the loss was not significant compared to the affirmation that water can be a separate venture from mining.

These cases established the basis of water law and, consequently, western law, which provided legal validity to both appropriative and riparian rights. Furthermore, the swift acquisition of mining land with water rights demonstrated the differentiation between water rights and mining rights. Nonetheless, the conflict between appropriative and riparian rights would be significantly tested in the latter half of the nineteenth century when corporations superseded cooperatives, resulting in a transformation of the valley.

Lux & Miller v. James Haggins

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the valley’s landscape underwent a significant transformation as verdant hills and wooded streams were replaced by flat, parceled lands divided by waterways of varying sizes. The once serene trout lakes were transformed into vast alfalfa fields serving as fodder for the livestock of the newly emerging vaqueros. Arax paints a picture of a valley plagued by a “fire sale that concentrated the best and most fertile parts of California in the hands of a grubby few.”[32] Among the largest monopolists of this era was the Southern Pacific Railroad, which, in 1862, received one hundred feet of land on either side of its tracks through a series of acts passed by the federal government. Before losing control over California, the Mexican government had given away 48,000 acres of land to friends and family through thirty pacts. The US Land Commission of California reviewed these land grants, approving twenty-four out of thirty. The Commission’s policies, such as the Swamp and Overflowed Lands Acts, were exploited by San Francisco capitalists who amassed over 170,000 acres of land in the lake basin. By 1871, around five hundred men would hold nine million acres of land in the valley. Only a select few, such as Henry Miller, however, would have a significant historical impact.

At the peak of his empire, Henry Miller held more land and water rights than any other person in the country, with his holdings estimated at 1.3 million acres. Miller’s journey to the West began at the age of fourteen in 1847 when he emigrated from Germany to New York, where he worked as a butcher and eventually opened his own shop. The allure of the West and its promise of gold prompted Miller to sell his shop and venture westward with empty pockets, however.[33] In 1851, a massive fire leveled much of the city, creating an opportunity for Miller to establish himself in the industry.[34] By 1857, Miller had begun to expand his business by purchasing 8,800 acres of land in the valley to maintain his herds, which totaled over 7,000 heads of cattle. His expansion garnered the attention of San Francisco’s second-largest meat packer, Charles Lux, and the two soon formed the infamous Miller & Lux partnership.

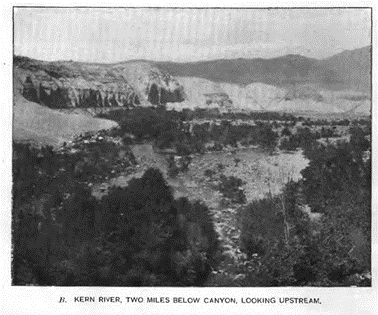

Miller & Lux repeatedly took advantage of the Swamp, Desert, and Overflowed Lands Acts to acquire vast amounts of cheap land in the valley. Miller would bring his herds of livestock to feed on the ten-foot tall tule reeds prevalent around the small lakes formed by the Foothill Rivers. By 1870, Miller & Lux owned between 328,000 and 450,000 acres in California and expanded into the San Joaquin Valley, particularly Kern County and its river.[35] Here, Miller & Lux encountered a competitor acquiring the Kern River (Figure 2).

James Ali Ben Haggin was born into a wealthy and prominent family in Kentucky, where he attended Centre College and practiced law along the cotton belt. The allure of the West beckoned him to pursue riches, however. Alongside his brother-in-law Lloyd Tevis and with the assistance of Senator George Hearst, Haggin invested in the Anaconda Copper Mine and Wells, Fargo & Company. Tevis would later become the president of Wells, Fargo & Company and Southern Pacific Railroad while also co-opening the largest gold and silver mine in the country with Haggin. In the 1870s, the Southern Pacific Railroad expanded its construction through Kern County, acquiring thousands of acres due to the 1862 acts. Haggin would also acquire Gates Ranch and its 52,000 acres of land in 1873.

Haggin’s land agent, William Carr, bought odd sections of railroad land along the Kern River while using dummy buyers for the even sections of land. By 1876, Haggin had acquired over 100,000 acres of land in Kern County and did so again the following year by abusing the land reclamation acts, which Miller & Lux also did.[36] Carr was a highly influential figure who came under criticism for his dubious practices. For example, he was instrumental in the making of many prominent politicians and businessmen during the 1870s and 1880s, designating politicians and dictating their votes. Carr initially arrived in Kern County to expand his personal landholdings but quickly realized that he could make more money and create more opportunities by working under Haggin and Tevis. Carr thus began purchasing controlling shares in the various water companies in the county. In 1873, independent farmers controlled the six major waterways in the county with the ability to irrigate 5,000 acres. Many companies never filed the paperwork to be companies under the state law but did so under Carr’s direction. This is how Carr’s predatory tendencies were given room to operate. He approached these newly formed corporations, often just being a single man or small group of farmers, and outlined the management, finance, and construction for a competent canal system. He convinced farmers to sell their remaining shares in their companies for this dream while promising that their land would skyrocket due to the creation of the canal system. By 1875, construction had begun on twelve canals capable of irrigating 70,000 acres, with the final canal completed in 1879.

In May 1877, Haggin and Carr constructed a diversion dam northwest of Bakersfield, causing uproar among the cattlemen and farmers south of the dam. Notably, Henry Miller, a prominent cattleman, was among those affected and initiated the Miller v. Haggin lawsuit. The situation was further exacerbated by the drought that ravaged the valley in 1877 and 1878. This drought had severe consequences for farmers and cattlemen, with the Kern River transforming into an alkaline mud hole producing grimy, rotten green water with a foul odor. The conditions were so severe that many cattle got their legs stuck in the alkaline mire, with their hides stripping off after being pulled free. The drying mud and sunbaked land created a barren desert with countless cattle succumbing to thirst, leaving behind nothing but their bleached bones and a ghastly stench. Miller alone lost over 60,000 cattle, and he held Haggin and Carr solely responsible for the drought. Miller and other riparian owners attempted to compromise by offering Haggins seventy-five percent of the water, with the remaining twenty-five percent divided amongst downstream users. This proposal was declined as they believed they could prevail in court.

On 12 May 1879, Miller & Lux, along with seven others, filed a lawsuit against Haggin to prevent the diversion of flowing water. According to Jeff R. Bremer’s article, “The Trial of the Century: ‘Lux v. Haggin’ and the Conflict Over Water Rights in Late Nineteenth-Century California,” the legal doctrines of riparian and appropriative rights were once again being challenged against each other. Bremer elaborates on how riparian rights came into use in California and how the state constitution remained neutral.[37] Haggin managed to position himself as a civilized businessman representing the working poor and supporting appropriative rights, while Miller was viewed as barbaric due to his practice of riparian rights. By excluding agricultural production and diverting water from already established farms, Haggins’ diversions ultimately caused the family farmer to lose.

On 15 April 1881, the trial began. Superior Court Judge Benjamin Brundage presided over the case despite his prior support of Haggin’s and Carr’s abuse of the Reclamation Acts. Both parties hired top lawyers to represent them, with Haggin’s lawyers planning to challenge Miller’s riparian rights by arguing that the Vista Slough was not a natural waterway, which would nullify Miller’s riparian rights. Miller simply had to prove that his land qualified as riparian. On 2 June 1881, the trial was moved to San Francisco. Miller’s legal team attempted to introduce evidence that Miller owned land along the Buena Vista Slough, but Brundage denied its inclusion. On 3 November 1881, Judge Brundage ruled in favor of Haggin, determining that Miller did not provide sufficient evidence and noting that the Kern River did not flow through the Buena Vista swamps.

In 1883 and 1884, the State Supreme Court reviewed the case based on legal errors on the part of Judge Brundage and his failure to omit evidence showing that Miller owned land on the slough before Haggins built his dam. The court argued that riparian rights had never been overturned before, and previous decisions favoring appropriative rights did not apply to this case because they were not relevant to mining. The court agreed to overturn the previous ruling and relitigated the case. On 26 April 1886, the Supreme Court of California concluded in favor of Miller against Haggins’ argument, which they concluded was an attempt to rewrite California law. The court also dismissed Haggins’ argument against riparian rights, concluding that water rights are property and stable property rights enable economic growth. The court did not completely reject appropriative rights but weakened them by limiting their application to public lands, with private lands always taking precedence.

Carr was furious, rallying statesmen and senators to petition the then Governor George Stoneman to call a special session to rewrite the law on water rights. The governor would call the special session on July 20 while heavily intoxicated. The special session was portrayed accurately and disgracefully, with votes being bought for $300 if the bill passed the assembly and another $600 if it passed the Senate. Newspapers openly criticized the affair between business and politics as showcasing the overt corruption in the state body. Carr’s forces were responsible for the demise of the bill after targeting the restructuring of the Supreme Court to remove two dissenting judges based on mental illness. Furthermore, this was done while doubling the remaining judge’s salary on the basis of overturning Lux v. Haggin.[38] Newspaper coverage and public outcry, as well as Miller’s funding, led to both the restructuring of the judiciary and the bill’s failure and the session closed on September 12, having accomplished only ruining the reputation of the state body.

After a protracted legal battle, a compromise granted Miller one-third of the water rights from March to August and divided the remaining two-thirds among the other defendants. Additionally, Lux and Miller agreed to provide storage for excess water from Haggin in Buena Vista. Furthermore, the two parties pledged to work together to maintain levees and canals on the river and to combat those who infringed on their riparian rights. The repercussions of this settlement were far-reaching, as it influenced the water laws of seventeen western states. The Wright Irrigation Act of 1887 was subsequently passed to provide water to those without riparian access and to enforce eminent domain to condemn some property holding water rights, thereby breaking up large monopolies and leading to the development of more agricultural land.

The Central Valley is now a vast expanse of flat farmland where food of all types grows abundantly, and concrete canals have replaced once pristine lakes and rivers. In his book, “The King of California: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire,” Mark Arax notes that the receding waters of Tulare Lake, due to the construction of ditches and canals, gave rise to the largest grain farm in the United States. Farmers rushed to plant seeds as fast as the water drew back, using horses and mules shod in wooden shoes to avoid getting stuck in the mire. Carl Ewald Grunsky, a US Geological Surveyor who arrived in the valley in 1898, documented the water situation, including the various canals and ditches. Grunsky described what was once Buena Vista and Kern Lake, noting that “Buena Vista had been shut off from the east from its connection with Kern Lake by means of high levee. Thus Kern River water is prevented from reaching Kern Lake, the bed of which is now dry arid land, and Buena Vista Lake is converted into a large reservoir.” Only government intervention can dismantle large monopolies exploiting riparian and appropriative rights. However, it was government action that often enabled such monopolies to form in the first place.

Appendix

Figure 1: “Photo of Yo-mut” [39]

Figure 2: “Kern River, Two Miles Below Canton, Looking Upstream” Carl Ewald Grunsky[40]

© 2023 The UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History

[1] Pedro Murillo is a California State University graduate (2023) in the field of history with emphasis in teaching. They are currently an educator who seeks to highlight overlooked stories that directly impact the average person.

[2] “Agricultural Water Use Efficiency,” California Department of Water Resources, https://water.ca.gov/Programs/Water-Use-And-Efficiency/Agricultural-Water-Use-Efficiency.

[3] Mark Arax and Rick Wartzman, The King of California (PublicAffaires, 2003), p. 46.

[4] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 49.

[5] George H. Derby. Report to the Secretary of War, Communication in Compliance with a Resolution to the Senate: A Report of the Tulare Valley. Senate Executive Documents no. 110, 32nd Cong., 1st sess. 1852, p. 8.

[6] John Muir, “Chapter 16: The Bee-Pastures,” The Mountains of California” (John Muir Education Project, Sierra Club California, 1894), https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/the_mountains_of_california/chapter_16.aspx.

[7] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Yokuts.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

[8] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p.48.

[9] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 62.

[10] Annie R. Mitchell, The Way It Was: A Colorful History of Tulare County, p. 16.

[11] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 48.

[12] Williams L. Preston, Vanishing Landscapes: Land and life in the Tulare Lake Basin, pp. 57-58.

[13] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 50.

[14] George W. Stewart, “The Indian War on Tule River,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 31, no. 2 (2011), p. 204.

[15] Annie R. Mitchell, “Major James D. Savage and the Tulareños,” California Historical Society Quarterly 28, no. 4 (1949), pp. 324–25.

[16] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 61.

[17] A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875 p. 782

[18] “1851-1852 – Eighteen Unratified Treaties between California Indians and the United States,” US Government Treaties and Reports, p.5.

[19] Noguchi Kumiko, “From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934,” (2009): p. 92.

[20] Noguchi Kumiko, “From Yokuts to Tule River Indians” p. 96.

[21] US Government Treaties and Reports, 1851-1852 – Eighteen Unratified Treaties between California Indians and the United States, 2016, p. 34.

[22] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 61.

[23] “Yoi-Mut, Last Survivor; Hanford, Calif; 1935; 13 Prints, 13 Negatives.” 2023. Online Archive of California. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf1q2nb5cs/?layout=metadata&brand=oac4.

[24] US Government Treaties and Reports, Eighteen Unratified Treaties, p. 45.

[25] Frank F. Latta, Handbook of Yokut Indians.

[26] Douglas R. Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush: Conflicts over Economic Points of View,” Western Historical Quarterly 14, No. 4 (Oct. 1983) pp. 416-417.

[27] Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush,” p.417.

[28] Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush,” p.420.

[29] Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush,” p.423.

[30] Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush,” p.426.

[31] Littlefield, “Water Rights during the California Gold Rush,” p.430.

[32] Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 72.

[33]Arax and Wartzman, The King of California, p. 74.

[34] Jeff R. Bremer, “The Trial of the Century: ‘Lux v. Haggin’ and the Conflict Over Water Rights in Late Nineteenth-Century California,” Southern California Quarterly 81, no. 2 (1999): p. 198.

[35] Jeff R. Bremer, “The Trial of the Century,” p. 200.

[36] Jeff R. Bremer, “The Trial of the Century,” p. 202.

[37] Jeff R. Bremer, “The Trial of the Century,” pp. 208-209.

[38] Jeff R. Bremer, “The Trial of the Century,” pp. 214-217.

[39] “Yoi-Mut, Last Survivor; Hanford, Calif; 1935; 13 Prints, 13 Negatives.” 2023. Online Archive of California. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf1q2nb5cs/?layout=metadata&brand=oac4.

[40] Bremer, Jeff R. “The Trial of the Century” p. 200