Hello, everyone! Thanks for tuning in! This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History podcast, and this season, we are sharing with you our archive stories of unboxing cool history stuff that we found in the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. Today I’m your host Hanna Kawamoto, a third-year History undergraduate and one of the editors of the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History.

In today’s episode of Unboxed, I am going to look at the nature of the graphic novel and comic as a form of historical insight, through the Chicano graphic novel and zine collection, and the ways it can bring new questions, criticisms, and understandings to light. For some images of today’s archival collection, please follow us on Instagram at @ucsbhistjournal. Nevertheless, I will do my best to describe certain images accordingly. Alright then, let’s see what our gray Hollinger box has in store for us today.

– Act 1 –

Before visiting the UCSB’s Library of Special Research Collections, I requested to look at the Chicano graphic novel and zine collection. I will admit, that part of it was because it was Hispanic Heritage Month, and the other was influenced by my personal involvement and love for the visual arts, especially graphic novels and comics. Honestly, comics and graphic novels have a bit of everything, and added with a touch of history (as they most often do) who knows what you can get! It can inspire and connect people. I mean, I fell in love with history through a graphic novel about Alexander Hamilton, and here I am now studying history at UCSB. Anyway, I digress. The collection contains over twenty graphic novels and zines created, drawn, and/or authored by Chicana and Chicano artists between the years 2003-2021.

I found that the topics discussed in the collection varied from issues of immigration, politics, identity, community, and entertainment. However, that is only the surface level of the themes highlighted, and sadly to discuss it all, I would need more than just one podcast. In light of the various topics, I did not have an objective per se on what I wished to find in this compilation. It was honestly quite fun not knowing what I would find. I used to think that you come into the archive with a solid agenda, but that is often not the reality. Even if you do come with one, expect it to be overturned very quickly. Nevertheless, once I did find something, I could never predict where it would take me. So, when I came across comic artist and author Dave Ortega’s De Narvaez, down the rabbit hole I went.

– Act 2 –

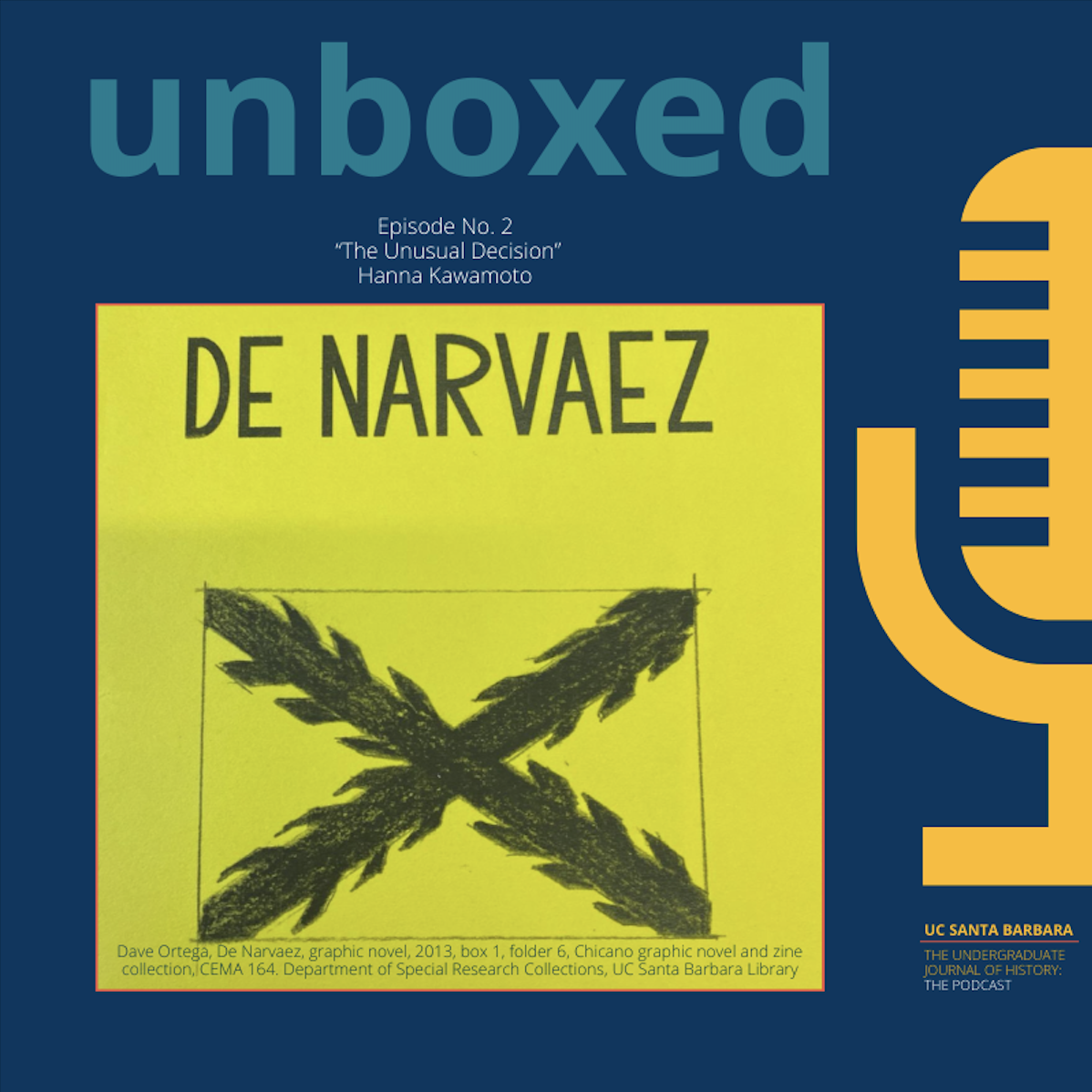

At first glance, there was not much to the source that would spark immediate interest. Yet, the more I thought about its simplicity, the more intrigued I became. Located in Box 1, Folder 6, Ortega’s De Narvaez is a thin neon yellow paper booklet, with the title in bold black ink. Below the title is a design in the shape of an X in black colored pencil, but with sharp, jagged edges that almost look like razor wire.

Fig. 2. De Narvaez reading the “Requerimiento.” (Drawing by Dave Ortega, De Narvaez, 2013, Department of Special Research Collections, UC

Santa Barbara Library).

The story begins with one image and one sentence depicting Spanish conquistador, Panfilo de Narváez, reading the Requerimiento (the Requirement), a sixteenth-century Spanish legal document that conquistadors read to justify Spanish control over land, and enslavement of its indigenous inhabitants.1 Already, the first page sets up the idea of another story about another Spanish conquistador, the issues, the consequences, and the effects of colonization by their hand. Another one of those stories that we have already heard and understand, right? At least that’s what I thought was Ortega’s intention. By the end of the story, I realized why he chose De Narváez and his expedition specifically to express a different perspective that engaged readers to further question the nature and outcome of this historical period.

To add a bit of context, Panfilo de Narváez was sent under orders by Charles V to gain control and colonize territory in Florida and westward. Between the years of 1527 and 1528, De Narváez arrived in Tampa Bay. He and over a hundred soldiers were to explore the interior of the land, while the ships continued to sail north to a designated harbor. The plan was for those on land to meet up with the ships. However, the ships, packed with food and supplies, docked in the wrong location, leaving Narváez and his crew stranded.2 Ortega illustrates the story from that point onward in the same one-image one-sentence format, along with more misfortune for the Narváez expedition.

Fig. 3. Capture of Apalachee hostages. (Drawing by Dave Ortega, De Narvaez, 2013, Department of Special Research Collections, UC

Santa Barbara Library).

They come across the Apalachee chiefdom and their attempts at colonization and enslavement were “outmatched and driven into the swamps.”3 The image alongside this sentence depicts three indigenous men from the Apalachee tribe, bounded by a single chain and held in place with a metal collar around each of their throats. Their hands are also tied together, allowing them to only walk from place to place. Nevertheless, Ortega illustrates each individual in a strong, defiant posture. Each man walks upright, almost like they already knew regardless of the physical chains that bound them, that the Narváez expedition had no idea what they were in for. With low rations and supplies, the crew struck out a plan to build barges out of “armor and other material” in hopes of reaching the Spanish settlement in Mexico. 4

The next two images related to their plan show the gradual deterioration of once a proud, confident expedition, reduced to a wavering, unsettled crew. In replace of the three Apalachee men, there are now three Spanish soldiers reduced to rags, taking out parts of trees to create a barge. The image after shows two soldiers eating the remains of one of their dead horses. By this part in the story, it did not look like the crew would even make it past building a barge. Despite the odds, Narváez and his crew were able to reach the Gulf of Mexico and it all appeared well until a storm and an “unusual decision” altered their course.5

Fig. 4. De Narvaez makes his decision. (Drawing by Dave Ortega, De Narvaez, 2013, Department of Special Research Collections, UC

Santa Barbara Library).

– Ad –

Elena: I hope you’re enjoying this episode of Unboxed. My name’s Elena–

Troy: And I’m Troy. Both Elena and I are members of the UCSB History Club and avid listeners of UNBOXED. That’s right. Troy.

Elena: The UCSB History Club is a big supporter of the Undergraduate Journal of History and hope that listeners of Unboxed will also consider joining us at History Club events.

Troy: We sure do Elena! The History Club at UC Santa Barbara is a student run campus club that meets weekly during the academic year. We host faculty and graduate student speakers as part of our fireside chat series. We also get together to play games and study, host potlucks, and holiday themed events.

Elena: And Troy, don’t forget that sometimes we even travel to local heritage sites around Santa Barbara. So if you want to get in on the fun, follow us on Instagram @UCSBhistoryclub. We hope to see you at the history club meetings soon. Okay, now let’s get back to this episode of Unboxed. Oh, I can’t wait to hear how this one ends.

– Act 3 –

Welcome back everyone! Let us get back to the story!

According to Ortega, Narváez “makes the unusual decision to separate” from the crew headed by his treasurer and marshal, Nuñez de Cabeza de Vaca, stating that “‘It is no longer time for one man to rule the other.’”6 The picture accompanying this text depicts either De Vaca or De Narváez standing and holding onto the lines of their makeshift boat as the storm rains upon them. Behind them are the remainders of the crew huddled over and nearly naked. Everyone, including the person standing gaze outward towards the reader. Perhaps it is the foreshadowing of the last time they would look upon one another and say their last words before they disappeared. Something about how they all looked at you made me feel unsettled.

The next and final page illustrates De Vaca and his crew stranded off the coast of Texas, sitting naked, with “the island natives” joining “them to weep.”7 By historical accounts, including De Vaca’s, he and three other men were the only ones who survived the expedition. And the indigenous peoples–the Hans and Capoques, and later the Karankawa and the Coahuiltecan tribes–that they came across on the coast enslaved them. This information along with the statement that Narváez said to De Vaca can be found in the latter’s autobiographical narrative, La relación.8 Given the way Ortega articulated and illustrated the story, it brings a different picture to light against the historical narrative.

Fig. 5. De Vaca’s crew stranded. (Drawing by Dave Ortega, De Narvaez, 2013, Department of Special Research Collections, UC

Santa Barbara Library).

The quote by Narváez in its original context was to allow De Vaca the choice to decide what is best for the latter to survive given the dire circumstances. They were at the end of their rope. Yet, Ortega’s medium and genre now align the meaning of the quote to Narváez and how his crew ruled over the indigenous peoples they encountered. Is that why Ortega depicted the indigenous inhabitants off the coast weeping with the survivors rather than as their enslavers? Does the presence of the survivors indicate to the indigenous peoples that they will no longer have their own choice to decide what is best for them to survive? Or perhaps, they cry not only for their own impending losses but for the losses they would have to impose upon others to survive?

– Summary –

Dave Ortega’s short graphic novel about the De Narváez expedition is both a clever retelling and a critique not just of the effects of colonization, but the complex implications regarding the individual liberties and rights of indigenous communities. The format of the one-sentence, one-image structure enables the story to be a form of visual interpretation that acknowledges the history and adds to the history of this moment. Of course, it would be insightful to hear what you all think about this story. How would you have interpreted it? What else would you discuss? What other genres can be a tool for diving deeper into history? I urge you to think about these questions, not just for this story, but for others that you may or might have come across. Even more so, I encourage you regardless of your major to take a trip to UCSB’s Library Special Research Collections. You never know what you might find.

– Sneak Peek –

Thanks for listening to this episode of Unboxed. Be sure to join us next week when Ava shares their archive story of unboxing details from the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and be sure to follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast. Thank you again and have a great day.

- Dave Ortega, De Narvaez, graphic novel, 2013, box 1, folder 6, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection, CEMA 164. Department of Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library (hereafter cited as De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection). ↩︎

- Jerald Milanich, “Narváez, Pánfilo de (c. 1478–1528),” Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2008.

↩︎ - De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection.

↩︎ - De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection.

↩︎ - De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection.

↩︎ - De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection.

↩︎ - De Narvaez, Chicano graphic novel and zine collection.

↩︎ - Cassander L. Smith, “Beyond the Mediation: Esteban, Cabeza de Vaca’s ‘Relación’, and a Narrative Negotiation,” Early American Literature 47, no. 2 (2012): 267–91, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41705661; Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, The Narrative of Alvar Nuñez Cabeça de Vaca, ed. and trans. Buckingham Smith (Washington D.C: [s.n.], 1851), p. 39. ↩︎