Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in!

Welcome to the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we’re diving into the archives, unearthing stories from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections, and exploring the fascinating and sometimes surprising stuff of history.

I’m your host, Vanessa Manakova, a third-year History major and a big fan of literary history! Today, on this episode of Unboxed, I’m bringing you something really intriguing: a Civil War-era poem I discovered in the William Wyles Collection.

For visuals of today’s archival find, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram @ucsbhistjournal,

Let’s dig in and see what that gray Hollinger box has in store for us today. Let’s get started!

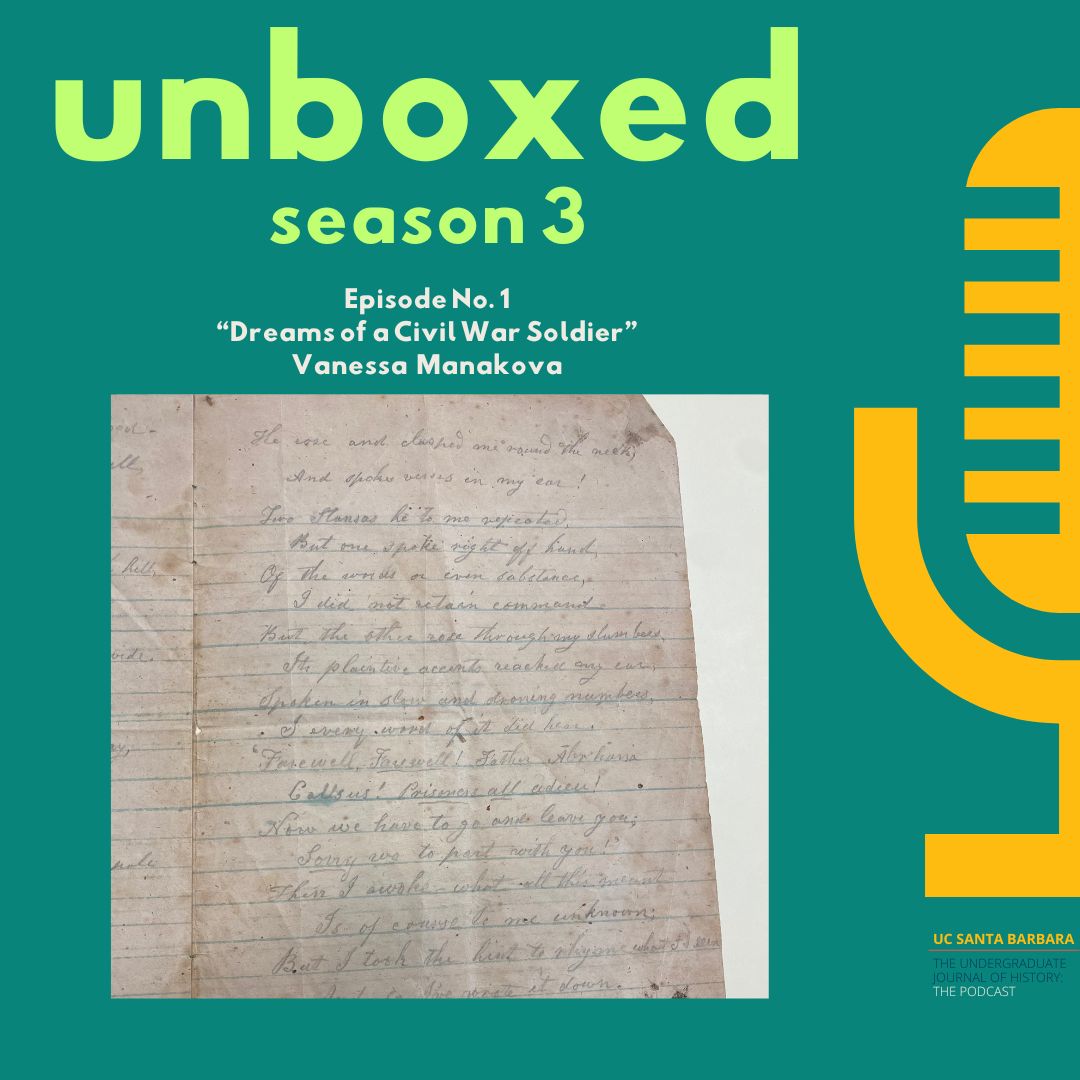

Right here in front of me is a fascinating little booklet, surprisingly well-preserved despite its age. It’s six pages long, and from what I can tell, it might’ve originally been part of a larger notebook but eventually came loose from wear and tear. The condition overall isn’t too bad—except for the first page, where there’s a pretty big stain, and, honestly, the rest of the pages aren’t much easier to read, with the writing faint and fading.

The poem comes from the William Wyles Collection. It is a six-page handwritten draft of an untitled poem that the unidentified author says was based on a series of dreams. It was supposedly written sometime around Feb. 25, 1865.

The Wyles Collection showcases an impressive array of “small collections” from the Civil War era, featuring over 1,000 unique manuscripts that include personal letters, diaries, photographs, and poems like the one presented here. It’s the largest collection on the West Coast dedicated to Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, its origins, and American westward expansion. The collection is named after William Wyles, a dedicated collector who poured his resources into preserving Lincoln’s legacy and the stories of this transformative period in American history.

I’ve tried to transcribe this poem as best I could. I’ll admit I had to get a little creative in some places to piece it together. But it’s such a captivating and mysterious piece that I couldn’t keep it to myself. Let’s unravel the story behind this intriguing poem.

The Poem starts:

Early in 1865, December,

I found myself on a plain.

[Some lines are obscured here, but the context hints at a reflection on the Confederacy or a battlefield.]

I thought I was dreaming.

I found myself standing in the line.

One being distinctly before me,

A mighty angel with a shining face.

On his back, there was a huge heart,

With the word Love, toward the rising sun.

The skies stood in solemn awe,

While he rose upward toward the tower.

His arm bearing a sword,

The blue and green were all aglow.

And the whole firmament fell, a grandeur,

His breast with this vividly [uncertain] word.

The sight fell fully on the south.

Already, we see this dream reflecting both the divine and the mortal: an angel with “Love” emblazoned on his back, facing toward the rising sun—perhaps symbolizing hope or reconciliation. But there’s also this sense of judgment, a “firmament” falling, as though even nature is reacting to the events of the war.

The poem continues:

His lip for a moment whispered faint prayer.

I stood riveted, awe-stricken and wondering,

Spread his wings and cried forth,

[This part is unclear, but perhaps he speaks of hope or freedom.]

But soon, I saw him going southward.

On, on he sailed, turned not about,

Still floating on over … [uncertain].

He floats there till he is worn out.

It’s clear that the angel’s southward journey is not just literal but symbolic, perhaps signifying the devastation of the Southern states during the war. But what does this mean for the author? They awaken and reflect on their vision:

Then I awoke—’twas but a vision,

But it seemed so much more plain.

Methought it overshadowed some instruction,

Even to a mind most vain.

Ah! ye vain and giddy-minded!

Me thinks to you may be applied

The chief picture of my vision,

Emblem of gay and haughty pride.

But wicked pride and mad ambition,

That cause so many men to quarrel,

Can’t rest on deeds decaying timber,

But will have to take their peril.

The author grapples with the meaning of the Civil War, likening the pride and ambition that fueled the conflict to “deeds of decaying timber”—a foundation destined to crumble. This is a sobering critique of human flaws.

Later in the poem, the author dreams of an “order book” signed by none other than George Washington and referencing General Sherman. It reads:

I dreamed again—a book was opened,

Its page displayed full to my view.

In it, I saw words, clear-pointed words,

But the letters were strange and mixed.

Puzzled, I turned down toward the bottom,

I saw what I’d ne’er seen before,

A signature in small “Roman Edge”

Signed, G. WASHINGTON as if done.

I saw some lines, an order book,

Such as officials keep at hand,

In which to note down all their orders,

What they require, what they command.

I now was curious to know.

To whom this order was given.

The more I felt as if ‘twere inspired—

An order fresh from Heaven!

The name I could not well make out,

But his title was quite clear.

There this in Roman and Italic—

SHERMAN, General ENGINEER.

This dream seems to bridge the moral ideals of America’s founding with the harsh realities of the Civil War. Sherman’s inclusion highlights the difficult decisions of wartime leadership. Known for his controversial “March to the Sea,” Sherman led a devastating scorched-earth military campaign from November to December 1864. The march destroyed everything in its path between Atlanta and Savannah, Georgia, targeting infrastructure and civilian property. While some may view these actions as excessive, they underscore the harsh realities of leadership during war. Additionally, the author interprets this as an “order fresh from Heaven,” suggesting a divine inevitability to the course of events.

The final sections of the poem delve deeper into the dreamscape, with haunting images of a “fallen oak,” symbolic of crumbling institutions, and a pale lawyer lying as though dead, representing those whose lives and potential were destroyed by the war.

A few nights more again, I went in dreamland,

I saw a wondrous in and around,|

First one way and then another,

Back across, around, and still on!

Next stood a firm oak, so it soon was out,

I leaned me on it—down it fell,

And burst asunder, I was astonished,

Saw ‘twas but a rotten shell.

The night beam passed straight over the rift,

And on the other side,

I saw the forks rise again,

Where all was cleared and smooth and wide.

I now saw men a-traveling on,

Out towards the utmost place,

But they told me I must stay another day,

And then I might go there again.

I now looked back to where I saw

The men a-digging clay;

I saw one there a lying down—looked pale,

Like he’d fainted, by the way.

I knew him once, he was a lawyer,

And he had been college bred,

But now his face of ashy paleness,

Reminded more of the dead!

I saw his lips move as to speak,

None did seem one word to hear.

The poem concludes with a powerful farewell, seeking guidance from Abraham, uncertain whether Abraham Lincoln or Abraham, the father of faith. In this case, Abraham could represent divine guidance, faith in uncertainty, and the possibility of redemption and reconciliation.

“Farewell, Farewell! Father Abraham!

Soldiers! Prisoners, all adieu!

Now we have to go and leave you,

Sorry, are to part with you.”

Then I awoke—what all this meant.

Is, of course, to me unknown.

But I took the hint to inform who I saw,

And so I’ve written it down.

The author awakens again, left uncertain of the meaning but compelled to record it. Perhaps these dreams served as a spiritual reckoning, urging reflection on the war’s moral cost and the possibility of redemption. Through its imagery of angels, books, and visions, this poem offers a deeply personal perspective on the Civil War, blending grief, hope, and the search for understanding in a time of national crisis.

Faith Barrett, author of To Fight Aloud is Very Brave, notes that Civil War Soldiers often carried poems tucked away in their pockets- on scraps of papers, inside books, or with letters and mementos. Poetry provided comfort, a way for soldiers to process the chaos and uncertainty of war.

The poem we explored today, written around February 1865 during the war’s final stretch, likely reflects a soldier’s attempt to reconcile the war’s devastation with hope for the future. Written in free verse—a style popularized in the mid-19th century by poets like Walt Whitman—it captures a free-flowing, conversational tone that mirrors natural thought and dream. This introspective and deeply personal style was common among Civil War soldiers, many of whom were amateur poets, probably also didn’t really know many strict rules. In this poem, you can almost hear the rhythm of the soldier’s thoughts unfolding like a dialogue with their dreams.

Additionally, like much of the Civil War poetry, this piece blends personal reflection with commentary on broader societal issues—most notably, the profound moral reckoning of the war. It grapples with the themes of pride, ambition, and redemption, all while reflecting on the chaos and cost of the conflict. This poem exemplifies how Civil War era poetry served not merely as documentation but also as a means of processing the war on both personal and collective levels.

During the Civil War, poetry was more than an art form—it was a lifeline. Soldiers used it to express their emotions, share their thoughts, and pass the time during long, uncertain days. Many sent their poems home to stay connected with loved ones, bridging the emotional distance created by the war. Amid chaos and hardship, poetry became a vital tool for coping and finding meaning in uncertainty.

[UCSB History Club Sponsor Message] (30 Seconds): The UCSB History Club is a big supporter of the Undergraduate Journal of History, and we hope that listeners of Unboxed will consider joining us at History Club Events. The History Club at UC Santa Barbara is a student-run campus club that meets weekly during the academic year. We host faculty and graduate student speakers as part of our Fireside Chat series, get together to play games and study, host potlucks, holiday-themed events, and travel to local heritage sites around Santa Barbara. You can find us on Instagram – address here. We hope to see you at a History Club meeting soon. Ok. Now back to this episode of Unboxed. Let’s hear how this one ends!

It’s 1865. You’re a soldier, worn down by months—maybe years—of relentless marching, harsh weather, and the constant threat of battle. The nights are cold, the days long, and the weight of everything you’ve seen presses heavy on your mind. Amid all this, you reach into your pocket and find a small scrap of paper—a poem you wrote, a keepsake from home, or maybe something recited around the campfire. It’s your connection to something bigger than the war that keeps you grounded.

This Unnamed poem today takes us into that world. It’s more than just words on paper—it’s a glimpse into a person’s heart grappling with the profound moral and emotional toll of the Civil War. The imagery of angels, fallen oaks, and faint voices speaks to the chaos and fragility of a nation at war, while the plea to “Father Abraham” reminds us of the hope for guidance and redemption in uncertain times.

Ultimately, poems in this time are like treasures –a lifeline for survival, a mirror for reflection, and a way to cling to something profoundly human amidst the inhumanity of war.

Thanks for joining me on this journey into this poem from the William Wyles Collection. Be sure to join us next week when my fellow editor, Ben Ortiz shares his archive story of unboxing Confederate Currency from the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and be sure to follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.

Until next time, this is Vanessa Manakova for the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast.