Intro (1 Min)

[intro music]

“Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in!

This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we are sharing our archive stories of unboxing the stuff of history from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections.

I’m your host, Kate Erickson, a third-year History of Public Policy and Law major, Museum Studies minor, and one of the UC Santa Barbara Undergraduate History Journal editors!

In today’s episode of Unboxed, we’re diving into the life and legacy of a true Santa Barbara icon, James “Bud” Bottoms. You might know him as the spirited artist behind those playful dolphin sculptures at the end of State Street, right by Stearns Wharf. However, he was also a passionate environmental activist who led a one-man charge to “Get Out Oil!”, otherwise known as GOO!, after the devastating oil spill of 1969. Today’s topic will build off of Valerie Holland’s amazing episode “Beyond the Spill,” which can be found in season 2 of Unboxed. Be sure to check it out!

For some images of today’s archival collection, such as Bud Bottoms’ creative cartoons and catchy songs, follow us on Instagram at @ucsbhistjournal.

Ok. Let’s see what that grey Hollinger box has in store for us today.

[sound effect]

Act I Duration: (3 Mins)

Alright! Let’s look at today’s collection, SBHC Mss 124, otherwise known as the Bud Bottoms GOO! collection. My interest in environmental activism drew me into this collection, especially considering that Santa Barbara 1969 Oil Spill was the caveat for Earth Day, connecting activism, art, and historical narrative. From powerful messaging to innovative protest designs and collaborations, Bud Bottoms’ creative advocacy offers a unique view of grassroots movements. Exploring this archive feels like uncovering the spirit of a community determined to challenge corporate and political complacency in the face of environmental crises. The first two boxes, which will make up today’s episode, contain an eclectic mix of correspondence, slides, ephemera, clippings, and Bud’s drawings to map the history of the GOO! movement. The collection also contains flat boxes with larger artifacts, including bold posters and more striking drawings by Bud and his artist friend, Don Freeman. Adding to the treasure trove are audiovisual gems like Ocean Sanctuary presents Coastal Crisis (1987), showing the dangers of offshore oil drilling, and California Crude by Janet Russell on VHS. For us history buffs, there’s even an Environmental History Round Table discussion (2017) and Stories of the Spill on DVD, offering a look back at how the 1969 oil spill sparked community action and became a symbol of environmental democracy. The next time you host a movie night, swing by the archives to check these out!

For now, I will unpack the details of boxes 1 and 2, which are most pertinent to Bud Bottoms’ work and legacy, along with the history of the Santa Barbara Oil Spill. In January 1969, off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, an oil rig blowout turned into one of the most significant environmental wake-up calls in U.S. history. Union Oil’s Platform A cracked open, and within days, around 3 million gallons of crude oil spilled into the Santa Barbara Channel, coating miles of coastline. Beaches turned black, and images of oil-covered birds and dead marine life hit the airwaves, shocking the nation. From the archives, I found the front page of the Santa Barbara Independent that displays a seagull covered in thick, black liquid covering its little body. Above the image, a headline blares “THE BIG SPILL” in all caps. In the article, the accident report is detailed and heart-wrenching. “The tragedy of it didn’t really hit until the time and tide and wind brought the oil to the beaches. Waves, full of oil, sprayed against the rocks. Water, brown with it, boiled onto the shore. Birds caught in it walked dazed on the beach, toppling over… Emergency bird cleaning stations opened up at several points around town. But for nearly all the birds, it was too late”. Without proper regulations, Santa Barbarans resorted to covering the beaches with straw and hay as it was a slightly effective absorbent against the globs of pitch-black oil crawling up the shore. A think piece titled “Santa Barbara’s Ghastly Oil Mess” put it best. “What has happened in the Santa Barbara channel is a clearcut and classic example of today’s tremendous problem of environmental pollution: the confrontation between immediate economic gain and the long-term public well-being.”

Yet, in addition to the environmental catastrophe, what made the 1969 oil spill so notorious was the lack of action. In their news release following the catastrophe, President Fred L. Hartley could not present a solution for Platform A that would not cause more destruction to the rig and the surrounding environment. In Article 1, he states, “Operations at Platform A and B on Federal lease Block 402 should not stop even if we and/or the government wanted to discontinue all activities. If we were to stop for any period of time, the resultant buildup in subsurface pressure would cause new seepage from the ocean floor and thus continually contaminate the shoreline”. Union Oil’s stance exposed a harsh truth: the company was utterly powerless to stop the leak without risking even greater destruction. This shocking admission unveiled the gaping holes in regulatory oversight, emphasizing the industry’s dangerous gamble between profit and environmental devastation.

The public outcry was intense, and the disaster did more than darken Santa Barbara’s shores. It ignited a local and national environmental activism movement, spurring individuals like our man of the hour, James “Bud” Bottoms, to take action.

[sound effect]

Act II Duration: (3 Mins)

A clipping from the January 31st, 1975 edition of the UCSB Nexus features a detailed interview with Bottoms regarding his foray into environmental activism. Though he and his friend Marvin Stuart had feared a disaster for years, Get Out Oil (GOO!) wasn’t formed until the day of the spill. Stuart called Bottoms and said, “We’ve got to get the oil out,” and the movement began. Stuart and Bottoms had previous experience in lobbying against oil, having led a successful referendum against an onshore oil facility in Carpinteria. They selected the former state senator, Alvin Weingand, to be the president of GOO! as he had been the leader in the Carpinteria movement. In the interview, Bottoms recalls, “‘We stuck our necks out first, and all of a sudden we had an organization. It was such a grass-roots thing’”.

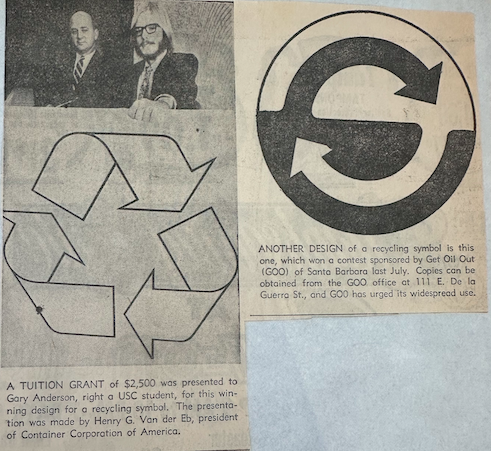

A fun and lesser-known tidbit about the GOO! Movement is its brush with recycling history! GOO!’s design for the iconic recycling symbol made it to the semifinals of a national contest. While USC student Gary Anderson’s now-famous three-arrow design took the top prize, GOO!’s entry, featuring a black-and-white pattern resembling a yin-yang, still made an impression. Maybe it was a nod to finding harmony in nature or just a stylish twist, but either way, it’s proof that GOO! brought creative flair to their environmental activism!

[sound effect]

[UCSB History Club Sponsor Message] (30 Seconds): The UCSB History Club is a big supporter of the Undergraduate Journal of History, and we hope that listeners of Unboxed will consider joining us at History Club Events. The History Club at UC Santa Barbara is a student-run campus club that meets weekly during the academic year. We host faculty and graduate student speakers as part of our Fireside Chat series, get together to play games and study, host potlucks, and holiday-themed events, and travel to local heritage sites around Santa Barbara. You can find us on Instagram – address here. We hope to see you at a History Club meeting soon. Ok. Now, back to this episode of Unboxed. Let’s hear how this one ends!

[sound effect]

Act III Duration: (3 Mins)

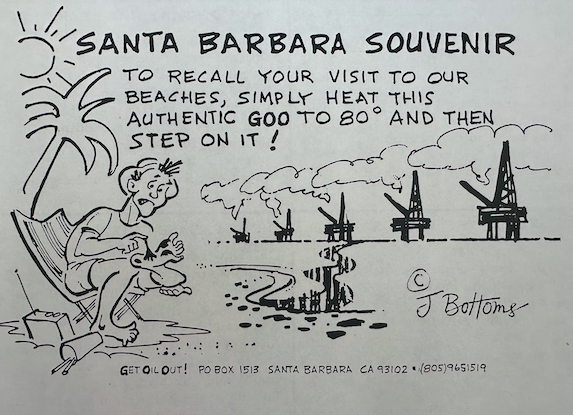

One of the most incredible parts of this collection are Bud Bottoms’ numerous cartoons, slogans, and songs created to advertise the purpose of GOO!. The first is titled “Santa Barbara Souvenir” with the caption: “To recall your visit to our beaches, simply heat this authentic Goo to 80 degrees and then step on it!” The cartoon shows a man lounging on a beach with a shocked expression as his feet are covered with black oil. In the distance, a line of oil rigs looms ominously on the horizon.

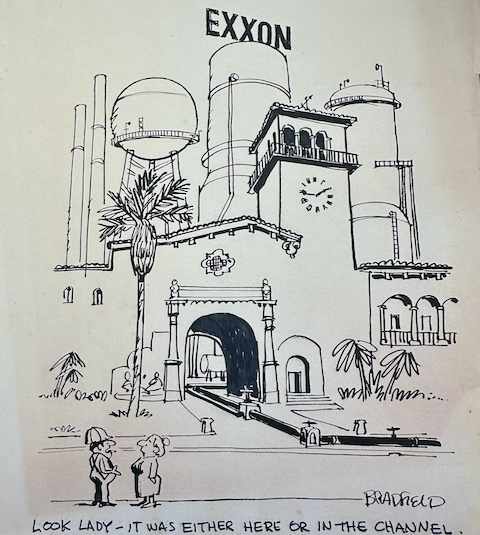

My personal favorite is a sketch of the iconic Santa Barbara Courthouse downtown. In the back, an oil company has built a refinery that overshadows the structure. In the foreground, a construction worker tells an angry woman, “Look, lady- it was either here or in the channel.” Bottoms never avoided exposing corporate interests’ absurdity and disregard for the environment. He invited viewers to question corporate influence on public spaces and natural resources, using humor and irony to point to the harmful consequences of placing profit over preservation. Like much of Bottoms’ legacy, this work resonates as a call to prioritize environmental integrity over exploitation.

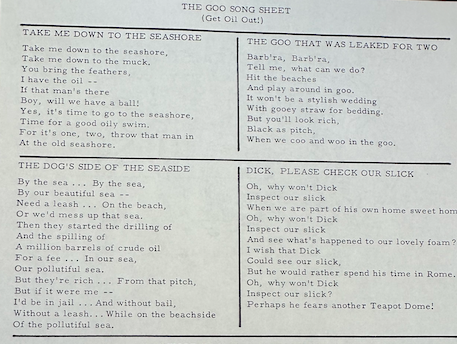

In addition to his cartoons, he also created a songbook for protestors. One song, to the tune of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” goes as such. “Take me down to the seashore, Take me down to the muck. You bring the feathers, I have the oil –If that man’s there Boy, will we have a ball! Yes, it’s time to go to the seashore, Time for a good oily swim. For it’s one, two, throw that man in At the old seashore’. Bottoms seems to ask the corporations and us what the actual cost of their actions is.

Bottoms’ art was not only impactful but accessible, opening the door for bigger audiences to conversations about corporate accountability, environmental degradation, and the role we all play, individually and as a society, in protecting our natural heritage.

[sound effect]

Summary (1 Min)

Bud Bottoms passed away in September 2018 at the age of 90. His legacy as a key figure in creative protesting and the formation of Earth Day continues to power environmental activism today. His work with GOO! in the aftermath of the Santa Barbara oil spill marked a turning point in the broader environmental movement and shaped a new generation of activists. His influence endures through his sculptures gracing shores worldwide and the consciousness he raised about the fragility of marine ecosystems. While residents of Santa Barbara know him best for his Dolphin Family sculpture, his art goes far beyond that. Like much of Bottoms’ legacy, his works resonate as a call to prioritize environmental integrity over exploitation.

[outro music]

Thanks for listening to this episode of Unboxed. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.