Introduction

[Intro Music]

“Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in!

This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we are sharing our archive stories, unboxing the stuff of history from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections.

I’m your host, Lauren Ko, a fourth-year undergraduate double majoring in History and Sociology at the lovely beachside University of California Santa Barbara.

In today’s episode of Unboxed, we are diving into a collection of propaganda from World War I and II in the form of various posters and one unique piece we will discuss. By breaking down the content and visual appeal of these archival prints, I hope to explore how propaganda shapes public perceptions, specifically those of the Allied nations during both world wars, and uncover what makes us consider an object “propaganda.” If you’re interested in today’s topics, check out Chynna Walker’s excellent episode “Ink, Paper, and Ideology,” which can be found in Unboxed season 2!

For some images of today’s archival collection, follow us on Instagram at @ucsbhistjournal.

Ok. Let’s see what this grey Hollinger box has inside today.

[Sound Effect]

Act I

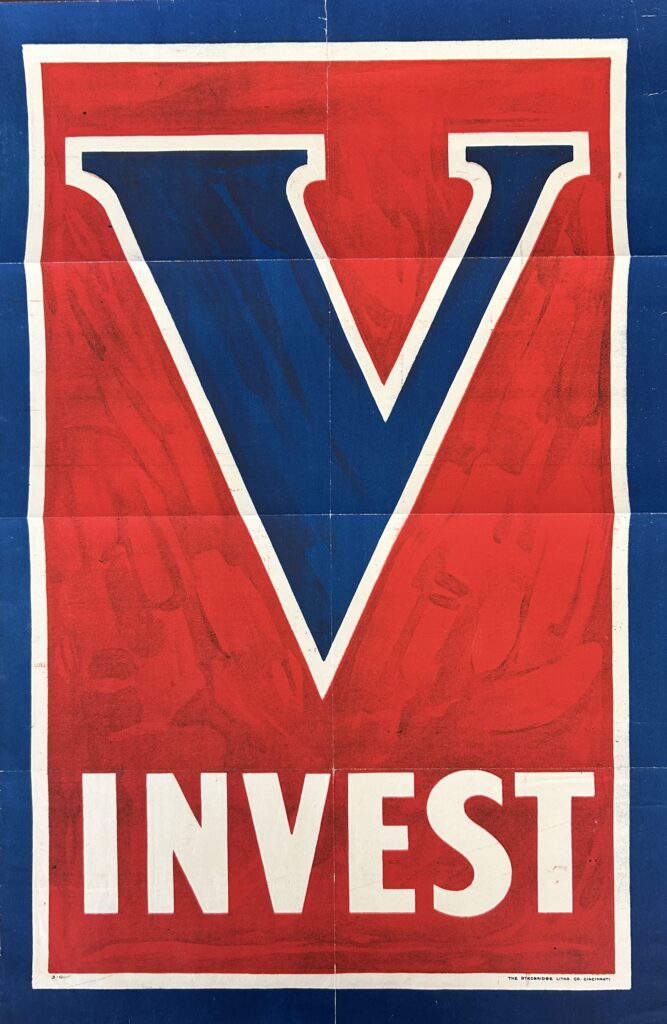

The collection we are looking at today is titled “World War I & II Poster Collection.” Housed under the call number Mss 342, it consists of one grey Hollinger box and a much larger poster storage box holding eighteen ginormous posters from Allied powers all over Europe and in America. Upon opening the larger box, I set my eyes on the first poster. A bold “V” for “victory” is painted across the poster, which reaches almost to my torso in height and is washed in vibrant red, white, and blue. This is what you can expect to see in this collection and what you might imagine when conceptualizing the idea of wartime propaganda. However, contrary to this initial presumption, the collection also contains one small but charming cookbook.

To provide a little historical context for the collection:

During World War I and II, propaganda was essential for governments to convince citizens to sacrifice their “freedoms” for the war effort. Soldiers had to be convinced to fight, and on the homefront, civilians were encouraged to buy National Defense bonds or subscribe to national loans to finance the enormous military expenditures, fill the growing deficits, and support soldiers. In France, posters popularised large-scale campaigns designed to stimulate generosity, and many artists participated (for example, Francisque Poulbot and Georges Redon). While initially, the vibrant colors, beautiful art, and bold slogans caught my attention, I later grew more interested in understanding how a cookbook, of all things, could be considered a propaganda tool.

[Sound Effect]

History Majors! Are you struggling with your major requirements? Having difficulty signing up for history classes? Do you have questions about writing a senior honors thesis?

Well, you’re in luck! Did you know the History Department has its own undergraduate academic advisor? That’s right, Kiara Actis has all these answers and more!

You can drop by her office, HSSB 4036, and speak to her in person on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 8 AM to Noon or from 12:30 PM until 4:30 PM.

If that doesn’t work, book and appointment online or email her at undergraduate-advisor@history.ucsb.edu.

Remember, Kiara is the HISTORY advisor. So, if you have questions about General Education or other UCSB requirements, contact the College of Letters and Sciences advisors. They’re better equipped to answer those questions.

But with that said, let’s get back to this episode of Unboxed.

[Sound Effect]

Act II

Before we get to our cookbook, let’s look at a couple of the posters this collection covets. This first poster is titled: “Women’s Army Corps.” The main focus of the poster is a painting by American artist Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer, depicting a young, white woman in a military uniform gazing hopefully into the sky, the shadow of armed forces behind her. The top of this evocative image reads: “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.”

Here is a strong example of integration propaganda, which aims to reinforce cultural norms and create a sense of shared, collective beliefs. Using the concept of an all-women military unit and a female figure as a focal point, the propagandist emphasizes unity and strength in female contributions to the war effort, fostering a sense of national pride and collective purpose hinged on female empowerment. This calls to mind the iconic poster, “Rosie the Riveter,” depicting a female factory worker flexing her muscle, urging other women to join the World War II effort with the declaration “We Can Do It!” Propaganda campaigns such as these encouraged women to move out of the domestic sphere; they became essential to the war effort, contributing overseas on the war front and in factories at home. It is important to note, however, that both idyllic women in these examples were white, as nonwhite women were welcomed into the labor force much less frequently than their white counterparts.

The tagline, “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory,” also evokes patriotic themes from the Civil War-era song, “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” tapping into the values of freedom and moral righteousness. The reference also adds a religious undertone, insinuating that this war was fought by divine command under the Christian faith. This imagery and messaging persuade the audience to see women’s military participation as acceptable and an honorable duty that aligns with their patriotic ideals.

[Sound Effect]

We also have in this collection a hand-drawn French propaganda poster for the 1940s American film Avant De T’Aimer (also known as “Not Wanted”), which illustrates how cinema and other forms of art can act as powerful vehicles for propaganda.

Art such as this expresses emotion while subtly promoting Western ideals of freedom, romance, and unity. The poster itself depicts the main leads in a passionate embrace, words in various languages strewn across the romantic imagery. The layering of multiple languages—French, English, and even Dutch—creates a sense of inclusivity and alliance among the nations, using language as a visual representation of unity across borders. The content of the movie and its promotional text matters less than the evidence of clear transnational cultural exchange and collaboration, at least within this specific poster, as this was an American film directed by British actor Ida Lupino and advertised in France.

Once again, propaganda wasn’t limited to militaristic messages but expanded to include lifestyle and emotional appeal. Unlike direct, overtly militaristic or ideological messaging, this approach to propaganda worked subtly to create a shared cultural identity for the Allied nations involved.

By examining the techniques these posters use to persuade their audience of certain wartime ideologies, we can also determine which techniques make our cookbook “propaganda” rather than a simple cookbook. But before we continue, let’s hear a quick word from our sponsor!

[Sound Effect]

Erick: I hope you’re enjoying this episode of Unboxed! My name is Erick, and I’m one of the editors at the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History. Today, I’m joined by Jasmine, a Member of the UCSB History Club. So, Jasmine—at your meetings, do you all just sit around debating who had the better mustache, Napoleon or Stalin?

Jasmine: Oh, absolutely. It gets heated. You’d be surprised how passionate people get about historical facial hair.

Erick: I can imagine! But really, what’s the History Club all about?

Jasmine: We’re all about bringing history to life—whether through discussions, guest speakers at our fireside chats, or just having fun with board games. We also organize off-campus events, giving students a break from academics while still engaging with history in exciting ways. We meet every Tuesday evening in HSSB 4020.

Erick: Sounds like a great time! So if you love history—or just want to debate legendary mustaches—check out the History Club! Follow them on Instagram @UCSBHistoryClub, and join their GroupMe to stay updated on upcoming events.

Erick: Stay tuned, and stay curious, Gauchos!

[Sound Effect]

Act III

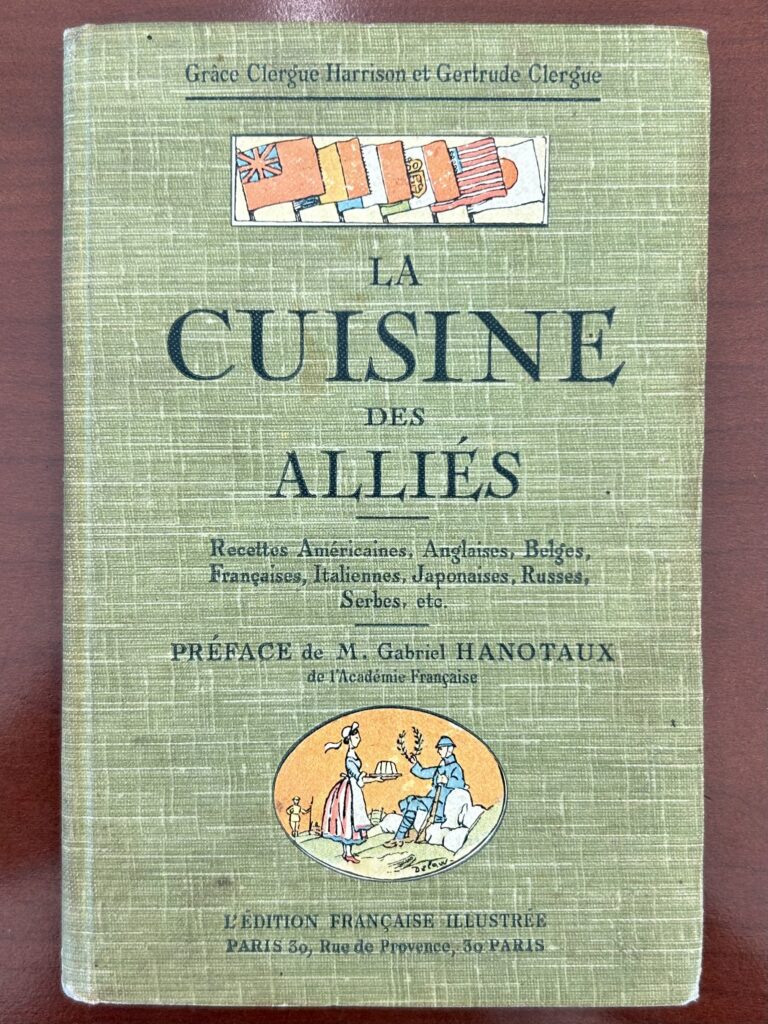

Finally, we arrive at the collection’s cookbook, published in 1918, titled La Cuisine Des Allies. Its appearance is modest: a small, green, canvas-bound book able to fit in the palm of my hand. On the front, a tiny ovular graphic illustrates a woman in traditionally domestic clothing offering a soldier a dish, victory laurels in the soldier’s hand. The cover depicts the military and civilians’ roles in the collective war effort. Just as the soldier symbolizes the fight for freedom, the woman represents the vital support from home, highlighting that everyone, from soldiers on the battlefield to homemakers in the kitchen, was part of the victory.

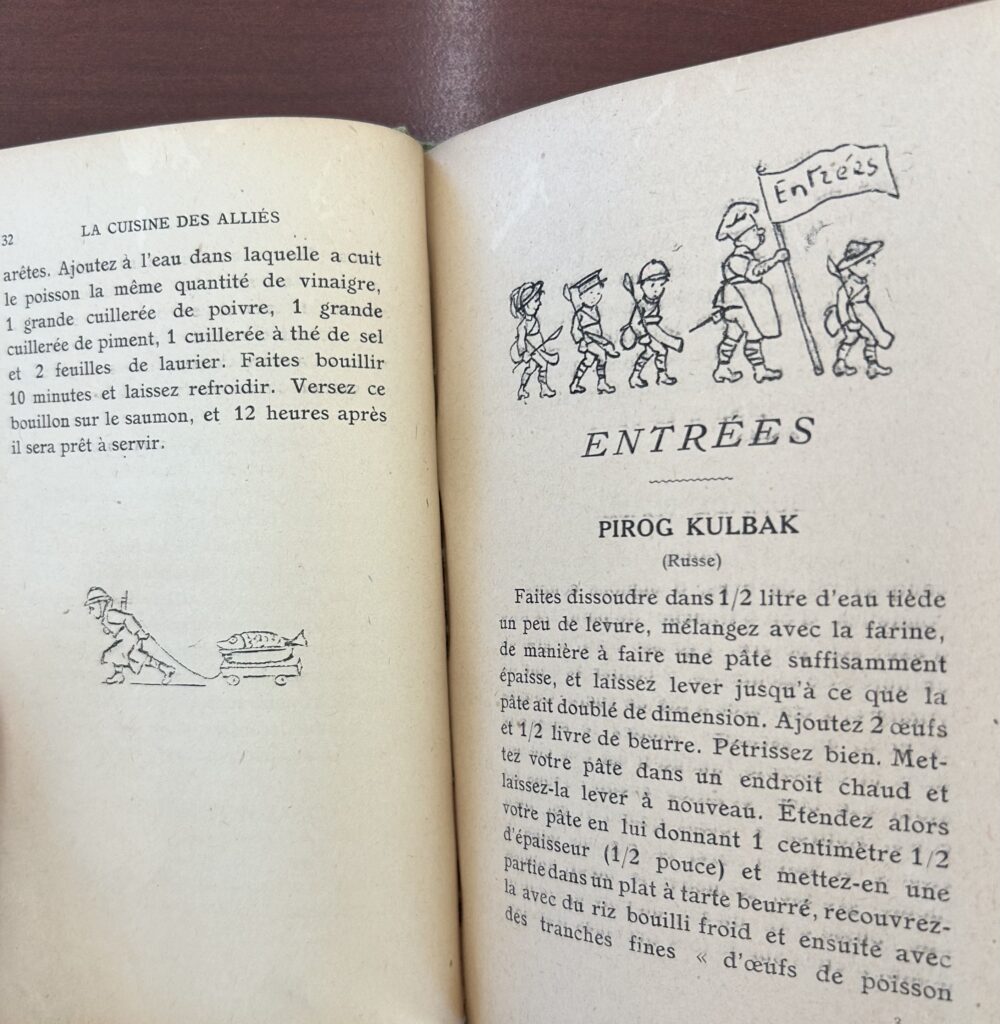

Other illustrations throughout the book remind us that WWI heavily contextualized this cookbook and defined its role as propaganda. Soldiers are depicted with kitchen utensils in the place of weapons, and flags can be seen interspersed throughout the pages. Although the text is entirely in French, this cookbook comprises a collection of recipes from across the Allied Powers—American, English, Belgian, French, Canadian, Italian, Russian, and Serbian.

Much like wartime propaganda posters encouraging women to join the workforce or save resources for the troops, this cookbook uses food, and more generally, women’s work of cooking and domesticity, as a rallying point. From a purely utilitarian standpoint, a cookbook like this would have encouraged rationing by offering easy recipes that require fewer resources. However, it also acts as a vehicle for other ideological messaging. Including recipes from across the Allied nations creates a narrative of shared sacrifice, cultural pride, and solidarity. Each recipe represents a different country’s culinary traditions, reinforcing a sense of unity across diverse cultures by celebrating each nation’s contributions, not only on the battlefield but in the daily lives of civilians.

The sense of camaraderie the cookbook fosters is made all the more evident when writers from America, Canada, and France refer to one another as “friends” in the introductory text. The preface uses common “munitions of the mind” to this effect, singing praises for America and European nations for “uniting to save civilization” while simultaneously demonizing the enemy through their cuisine. The author writes, “These heavy German stomachs, this heavy German food, heavy German complexions are responsible for the heavy German culture and the terrible bestiality of their war. Such bodies, such souls!” By deprecating the enemy’s culture, the Allied powers place themselves in a position of moral superiority and cultural refinement.

This calls to mind the same rhetoric Europe and America use in their justifications for imperialism that their domination over others is a righteous mission to civilize “primitive” or “inferior” societies. This concept of ethnonationalism emerged in the early 20th century in the interwar period between World War I and World War II. It defined much of the “us vs. them” wartime sentiment, which pit nations against their own ethnic minorities and international “others.” This was especially relevant to World War II, in particular, as ethnonationalism is associated with the rise of fascist ideologies like Nazism.

The author also notes in the preface that large sums from the book sales in America and Canada were sent overseas to aid in European refugee funding, meaning the book is also a donation to the war effort and cultural branch between Allied nations. It subtly promotes the idea that the Allied nations, while diverse, share a common humanity and a commitment to sustaining each other through hardship. By normalizing the blending of cultures and traditions, the cookbook frames the Allies as military partners and a global family united by shared values of resilience, generosity, and hope. In this way, La Cuisine Des Allies embodies a quieter yet equally powerful form of propaganda — one that unites through the familiar comforts of food and the spirit of communal effort.

Now that we have a better understanding of what makes a common item or piece of media “propaganda,” we are still left with one question: What is the legacy of this type of wartime propaganda today? Are we still susceptible to tactics that might manipulate our perceptions even with modern tools and media? Perhaps this collection better serves as a reminder always to think deeper when presented with a piece of media, even if it doesn’t initially appear to have an ideological message.

[Sound Effect]

Conclusion

In this episode, we explored a collection of WWI and WWII propaganda, including posters and a unique cookbook, to analyze how these materials shaped public perception in the Allied nations. Through posters like “Women’s Army Corps” and “Avant De T’Aimer,” the collection reveals how art and cinema subtly reinforced ideals of collaboration, freedom, and shared sacrifice. Each piece exemplifies how propaganda uses integration tactics to promote cultural solidarity and moral duty among civilians. The cookbook La Cuisine Des Allies is a less obvious form of propaganda, using recipes from Allied nations to symbolize unity across borders. Through shared culinary traditions, the book frames the Allies as a global family bound by resilience and generosity against their “barbaric” enemies. Because the nature of a cookbook is domestic, it immediately targets women in the home with a private, more personal vehicle for its propagandistic agenda. Compared to the public and clear-cut propaganda posters, cookbooks may not seem like propaganda. Because the forms of propaganda are so varied, collections such as this one serve as a reminder that anything can be considered propaganda if created with an agenda, and we should be mindful to address any information we come across with caution, no matter how it is embodied.

[Sound Effect]

Thank you for listening to this episode of Unboxed. Be sure to tune in to the next episode, where Enri will talk about Upton Sinclair’s 1934 campaign for Governor of California. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.

[Outro Music]