“Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in!

This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we are sharing our archive stories of unboxing the stuff of history from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections.

I’m your host, Sara Stevens, a third-year history major at UCSB.

In today’s episode of Unboxed, we dig into the Atomic Age Collection, which contains a variety of pamphlets, brochures, and other ephemera that show just how deep the atomic age permeated every aspect of life in the United States after World War II, from religion, to pop culture, to the way people styled their kitchens.

For some images of today’s archival collection, follow us on Instagram at @historicaljournal.ucsb.

Ok. Let’s see what that grey Hollinger box has in store for us today.

ACT I

Today, we look into the far-reaching Atomic Age collection here at UCSB, which contains four boxes in total, but I focused on the second box. The items date from 1946-1971 and cover a range of atomic age topics from various sources. Some pieces of this collection were purchased on eBay or from other vendors, and some items were donated, allowing us to research and look into the atomic age. Across all walks of life, people were grappling with the novelty of nuclear power and its potential consequences. Many of the items in this collection are pamphlets on the atomic age and nuclear power as they relate to military endeavors, religion, and academia. For example, Martin De Hann, the founder of Radio Bible Class, published “The Atomic Bomb in the Light of Scripture” after its radio broadcast. The small red booklet contains four sermons, all framing the scientific aspects of the bomb through a theological lens, and it was not the only item in the archive to do so. A copy of a lecture titled “The Atomic Age” by J. Robert Oppenheimer, a pocket card detailing the effects of nuclear bombs, and an advertisement for the newest edition of “Atomic Power with God” are all items in the collection that show how the topic of atomic energy was unavoidable. If hearing about the dangers of nuclear power through endless pamphlets, lectures, and radio shows wasn’t enough, you could also keep a pair of atom bomb-shaped salt and pepper shakers to remind yourself. The secret of nuclear power had been discovered and unlocked, promoting a new way of living in the atomic age.

Alex: History Majors! Are you struggling with your major requirements? Having difficulty signing up for history classes? Do you have questions about writing a senior honors thesis? Well, you’re in luck! Did you know the History Department has its own undergraduate academic advisor? That’s right, Kiara Actis has all these answers and more! You can drop by her office, HSSB 4036, and speak to her in person on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 8 AM to Noon or from 12:30 PM until 4:30 PM. If that doesn’t work, book an appointment online or email her at undergraduate-advisor@history.ucsb.edu. Remember, Kiara is the HISTORY advisor. So, if you have questions about General Education or other UCSB requirements, contact the College of Letters and Sciences advisors. They’re better equipped to answer those questions. But with that said, let’s get back to this episode of Unboxed.

ACT II

The United States Government released a booklet, found in the collection, called “Survival Under Atomic Attack,” which detailed the precautions citizens should take if faced with a nuclear attack. The emphasis in these booklets was dispelling myths about nuclear weapons and radiation as they were such new concepts. Citizens were warned through these booklets that the blast, rather than radiation, was the most dangerous part of a nuclear detonation. The emphasis in these pamphlets is quelling myths and misinformation about nuclear weapons, with the last survival tip being not to start rumors, as a single rumor could cost you your life. Regarding military training, the United States Army and Air Force training manuals focused on atomic defense and radiation and introduced nuclear weapons, training classes. The Atomic Weapons Training folder contains a multiple-choice exam from one of these classes, telling us about how those in the military were taught to think of atomic defense and nuclear weapons. Another pamphlet in the collection that shows the extent to which the war effort and subsequent feelings about the war were communal is titled “Oak Ridge Tennessee: The Atomic City,” which highlights the company town that existed in Oak Ridge during the Manhattan Project. To maintain secrecy, the project had to be carried out in a location with few existing industries, and to combat this issue, the designers of the Manhattan Project built towns complete with housing, schools, and jobs to incentivize potential residents. The pamphlet contains images of various scenes of life in the Atomic City, highlighting its importance and commitment to normalcy. Despite the intense changes in the lives of those who lived in Oak Ridge, there was a commitment to routine and community that made life feel normal. Images included citizens watching baseball games, hanging laundry, and posing in front of the B-25 bomber Sunday Punch donated to the US Air Force by Oak Ridge construction workers. The creation of the bomb was a communal effort that ingrained atomic power into society. After the bomb was used, this became true for all aspects of society. The idea of atomic communities spread across America, promoting the new atomic home.

Erick: I hope you’re enjoying this episode of Unboxed! My name is Erick, and I’m one of the editors at the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History. Today, I’m joined by Jasmine, a Member of the UCSB History Club. So, Jasmine—at your meetings, do you all just sit around debating who had the better mustache, Napoleon or Stalin?

Jasmine: Oh, absolutely. It gets heated. You’d be surprised how passionate people get about historical facial hair.

Erick: I can imagine! But really, what’s the History Club all about?

Jasmine: We’re all about bringing history to life—whether through discussions, guest speakers at our fireside chats, or just having fun with board games. We also organize off-campus events, giving students a break from academics while still engaging with history in exciting ways. We meet every Tuesday evening in HSSB 4020.

Erick: Sounds like a great time! So if you love history—or just want to debate legendary mustaches—check out the History Club! Follow them on Instagram @UCSBHistoryClub, and join their GroupMe to stay updated on upcoming events.

Erick: Stay tuned, and stay curious, Gauchos!

ACT III

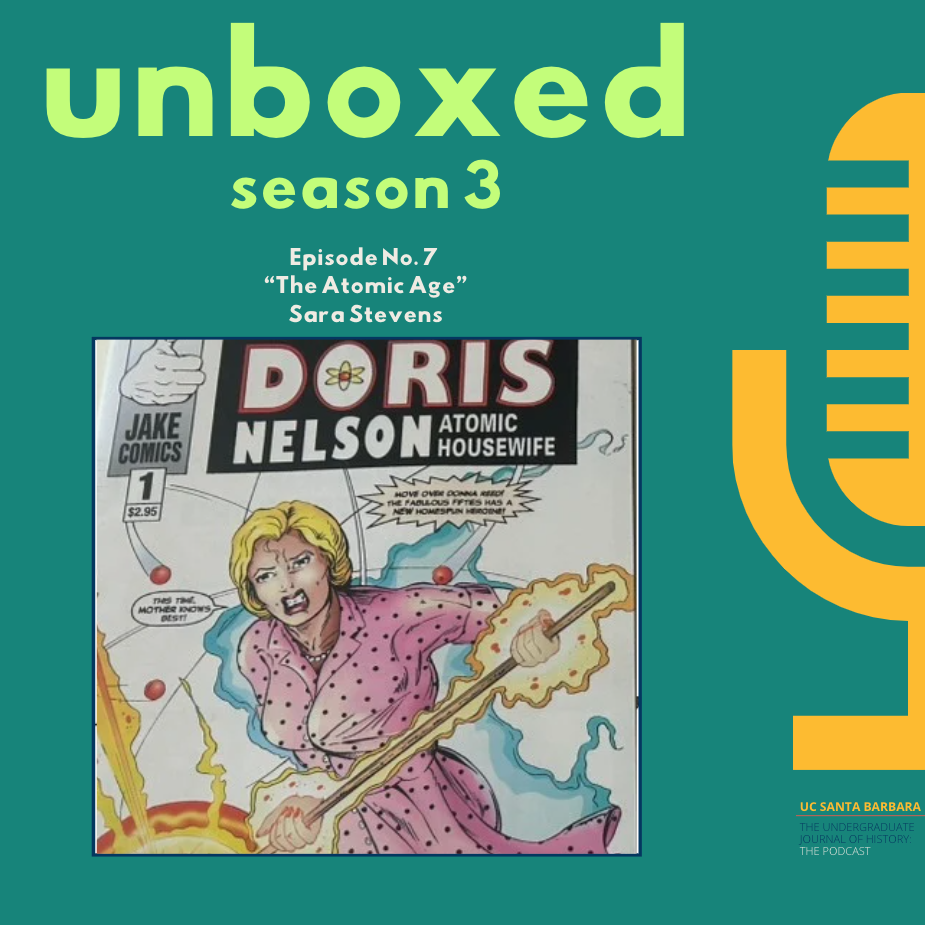

These various interactions with nuclear power inevitably influenced the culture in which they existed. From how you decorated your kitchen to the comic books you read, the atomic age ushered in new changes. Beyond Spiderman and The Hulk, a variety of lesser-known atomic superheroes and comics also existed during this time. One of these comics, “Doris Nelson Atomic Housewife,” similarly combines the idea of the perfect atomic age family with the ever-present threat of nuclear warfare. In Doris’s case, luckily, no nuclear warfare ensues. Instead, she gains superpowers that affect her role as a housewife. In this case, despite the fears of radiation promoted through the earlier pamphlets, radiation affects Doris positively.

Rather than setting her back, the atomic age and its technology gave her new powers, similar to the new vacuums and kitchen aid appliances of the 50s. American values and safety became the same once people took to defending their freedoms in a post-war world. However, despite these colorful images and appliances, it’s clear that fear of nuclear power ran deep, and the image of perfection was used to mask that fear. Similar to how an Atomic City existed to commit everyone to a communal war effort, the atomic home committed every American to preserve a particular cultural ideal after the war. This was subtly reinforced by the pamphlets and information Americans received from those in power about the dangers of nuclear war. The introduction of this power meant a loss of control for many Americans. Many people did not know what the future held. Despite this uncertainty, people could still take control over their domestic lives, While not written until 2004 by Whitney Matheson, a book in the collection called “Atomic Home: A Guided Tour of the American Dream” showcases images of the advertisements of the Atomic Age, which present new blenders and dryers as the essential inventions of the future, guiding American homes into a new era. After all, “The worst thing a family can do during the Atomic Age is express dissatisfaction. Even the furniture reflects a carefree attitude.” Patriotism during this time overlapped with the idea that progress was the path forward, and dwelling on the potential negative effects of nuclear energy was unpatriotic. Americans became models of perfection and progress, focusing on the opportunities of the future rather than the mistakes of the past. The cultural phenomenon that took place after the introduction of nuclear weapons starkly contrasted with the reality. While atomic homes may have looked perfect from the outside, families were simultaneously preparing for and thinking about a potential nuclear attack. However, this also didn’t stop the Atomic Age from taking over pop culture.

Conclusion:

The information that Americans were receiving from multiple channels was overwhelming them with contradicting views of the future of nuclear power. Academics like J. Robert Oppenheimer and religious figures like Martin de Hann framed nuclear power in terms of their respective fields, discussing opportunities for progress as well as potential complications. The United States Government took a slightly different approach with their shared information. While the portrayal of the bombs’ creation was framed in a positive light with the Oak Ridge pamphlet, the effects of the bomb needed to be prepared for. The government was providing information on how to survive an atomic attack, build a bomb shelter, and face nuclear war. The facade of community and patriotism was used to mask these harsher realities, but the information was presented in a way that made both realities possible for American families. The atomic home moved to the forefront to keep up this patriotism presentation. Atomic homes were centered around an idea of perfection, a two-and-a-half kid picket fence home that existed to mask the fear of nuclear war. The cultural presentations of the atomic home, like those presented in the Doris Nelson comic, mirrored these expectations, highlighting the traditional family values of the nuclear age while also dramatizing the opportunities for progress, such as through superpowers. Progress had to be positive, and the atomic home highlighted the limitless possibilities of futuristic technology, reflecting a larger hope that the technological advancements of nuclear power would reap similar benefits.

Thanks for listening to this episode of Unboxed. Be sure to join us next week when Danika shares their archive story of unboxing the UCSB riots from the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @historicaljournal.ucsb, and be sure to follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.