Intro (1 Min)

“Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in!

This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we are sharing our archive stories of unboxing the stuff of history from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections.

I’m your host, Danika.

In today’s Unboxed episode, we will discuss the Isla Vista Riots from 1968 to 1972.

I first visited the UCSB University archives last year. Walking back into the archives, a wave of nostalgia hit me as I remembered all of the unique and various collections I had checked out last year for my podcast episode. This year, I decided to look closer to home, to Santa Barbara. This led me to find the “Guide to the University of California, Santa Barbara, College of Letters and Science, Isla Vista Riots Collection.”

For some images of today’s archival collection, follow us on Instagram at @ucsbhistjournal.

Ok. Let’s see what that grey Hollinger box has in store for us today.

[sound effect]

Act 1

Today, we will be diving into the UCSB Riots. 1965 to 1970 marked a turbulent period for the US. The Vietnam War and civil rights protests transformed America. However, these national events were not just headlines to the students of IV. Minority students felt unsupported and unseen by their administration, and many male college students were being drafted for the Vietnam War.

As a result, Isla Vista quickly became a center for counterculture. However, this episode will specifically focus on student protests between 1968 and 1972 that occurred as a result of the civil rights movement and America’s direct involvement in Vietnam.

This collection contains materials from the College of Letters and Science on the various student protests in the late 1960s and 1970s. It includes materials on the ethnic studies protests for Black Studies and Chicano Studies. The collection included many folders, all organized by year and subject. The collection is organized by the following:

One- Student unrest, 1968-1972

Two-Demonstrations, 1970

Three- X-100 National crisis courses, 1968-1972

And finally- Four Student Disorders, 1975

Our episode begins in 1970 with a letter from the Vice-Chancellor of Academic Affairs at the time, A. Russell Buchanan. The letter is in response to the strikes and work stoppages. He writes, “In the light of recent events, I wish to remind you of University policy in this area… Employees of the University, after appropriate due process, are subject to disciplinary sanctions if they fail to perform their regularly assigned duties… Students may determine for themselves whether to attend classes.”

Many university employees stood in solidarity with their students, striking against the administration. This meant that many faculty members did not attend their classes, canceled classes, or simply did not show up for work.

However, let’s go back to 1968 to examine how these strikes began.

Marked by turmoil and change, 1968 was a turning point in US history.

The Civil Rights Act passed on April 11, 1968, is a landmark law that followed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended racial segregation in schools, the workplace, and public accommodations. The 1968 Act prohibited discrimination in housing based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, and familial status.

Even though this act was passed in April, many UCSB students still faced discrimination and injustices. As a result, on October 14, 1968, Black Student Union members demanded that UCSB support Black students on campus and implement a Black Studies Department to educate students and faculty. They were tired of being ignored, so twelve members pioneered a movement on campus, barricading themselves in the North Hall computer center. They called it the North Hall takeover.

According to an issue of El Gaucho, published on October 22, 1968, Chancellor Cheadle issued a statement. He stated that the Judicial Council recommended that the students be placed on “suspended suspension,” meaning that these students were suspended from the University, but the sentence was deferred as long as the students abided by University rules.

However, things only escalated from there.

Act 2

Three months after the North Hall Takeover, the UCSB administration had yet to honor any of the Black Student Union’s demands. As a result, students rose again and continued to push for necessary changes on campus.

The United Front. 1969. A statement dated February 2, 1969, from the United Front reads, “The United Front stands committed to justice in its fullest sense. We will never compromise the interests of any oppressed people, realizing that the interests of any one group cannot be isolated and dealt with separately from the interests of all oppressed people. Disunity and factionalism serve the interests of the powerful and betray the interests of the oppressed. We are all in it together.”

The United Front demands were built upon the original eight demands from the North Hall Takeover. They presented their demands to the administration, and the administration requested a private meeting to discuss their status. Instead, the United Front held a public meeting in Campbell Hall, inviting the Chancellor to address these issues openly with the students.

Chancellor Cheadle only stayed for an hour and a half, leaving students disappointed with his comments. As a result, the United Front agreed to engage in private conversations. However, only a week later, El Gaucho’s headlines read “Arrests, ‘Politically’ Motivated” on February 4th, 1969. This headline responded to seven arrests of the Black Student Union. The El Gaucho article claims that these arrests are an attempt to discredit the BSU and its demands. Following the arrests, the United Front released a document regarding the administration’s progress. In their letter, they write that the dialogue had been suspended due to blatant political harassment of the BSU leadership and that they demand that the dialogue begin immediately. The letter ends with “All Power to the People!”

On February 17th, around 1,000 students held a three-day demonstration at the UCEN involving classroom sit-ins, rallies, and marches. On February 26th, the United Front released statements explaining their commitment to justice. The Chancellor granted their demands of Malcolm X Hall, which still stands today.

[sound effect]

UCSB History Club Ad.

[sound effect]

Act 3

Our archive fast-forwards to 1972. However, it is essential to note that in 1970, UCSB experienced a series of violent protests and riots known as the Isla Vista riots. A speech given by William Kunstler sparked the riots. Students sought social justice at UCSB and peacefully protested at Perfect Park. However, some students sought to use bolder moves. On February 27th, 1970, a group of UCSB students protested, boycotted, and set fire to the Bank of America in Isla Vista. Students saw the bank as a symbol of capitalism and protested them after they gave illegal loans to South Africa and supported apartheid. This was an important event in Isla Vista’s history of social unrest and justice. If you want to hear more about this, make sure to check out Sophia’s episode, episode 9 of this season!

In 1972, each escalation of US involvement in the war brought a new wave of student protests.

Students nationwide hosted demonstrations to protest the Vietnam War during “International Peace Week.” Labeled Antiwar Week by the Daily-Nexus, UCSB students hosted rallies, strikes, and protests all over campus. These included movie showings, theater productions, and even artwork. Students criticized the US government and called for peace. However, when Nixon implemented Operation Linebacker in April 1972, UCSB students grew furious. Two thousand five hundred students shut down the Santa Barbara Airport.

On May 10th, the Daily Nexus reported that 1,000 UCSB students gathered on the UCen lawn to continue anti-war rallies. The following day, Governor Ronald Reagan came to UCSB and was greeted by 1,000 protestors.

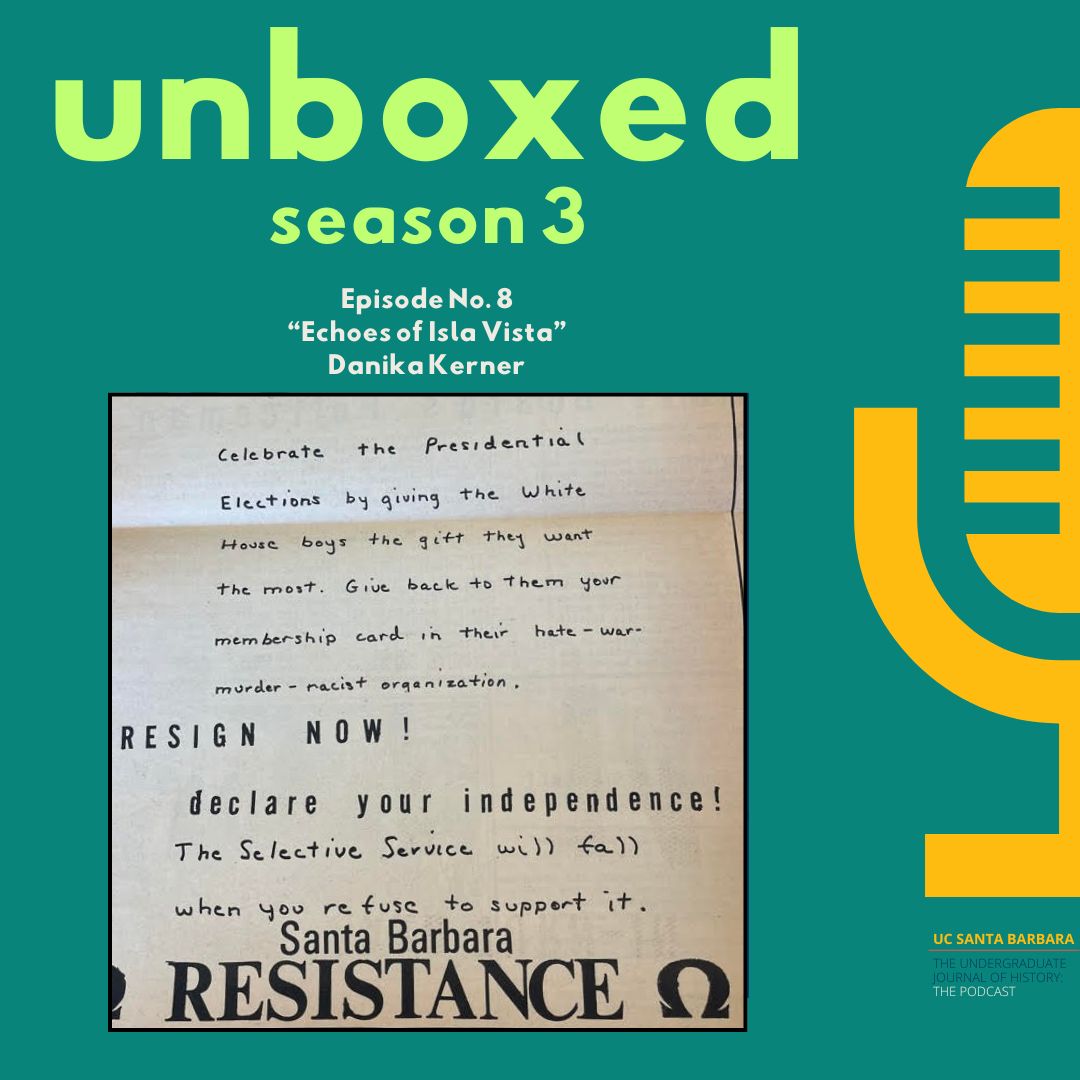

However, my favorite part of the collection includes a poster headlined Draft Card Turn-in. The poster read, “Celebrate the presidential elections by giving the White House boys the gift they want the most. Give back to them your membership card in their hate-war murder-racist organization. The Selective Service will fall when you refuse to support it,” Signed the Santa Barbara Resistance. UCSB, like so many other college campuses, helped raise awareness of the atrocities committed overseas. Ultimately, the student activism present at UCSB helped bring antiwar ideas and values to the broader public.

The archive ended with rally posters. The first rally poster, a fight for student rights, is for Monday at noon. The student demands include that Chancellor Cheadle reinstate the Black Studies research unit and form an Asian-American studies department. These rally posters are even similar to those that can be seen today.

Protests are seen in every major American city and on most college campuses, including UCSB. UCSB has always had the record of being a party school, so much so that it was ranked 2025 Top Party schools in America according to Niche, a college review site. However, the early 70s marked a shift for UCSB’s reputation from that of a party school to a center of protest and counterculture. Not only did students champion civil rights, but they also joined students nationwide in Vietnam War protests, something that played a significant role in generating public opposition to war and the US withdrawal of troops from Vietnam.

Malcolm X Hall, the Burning of the Bank of America, student rallies, and fighting the administration are essential parts of UCSB’s history. The next time you walk past North Hall, make sure to check out the murals on the walls. They tell the story of not only UCSB history but also black history. These murals show that change is possible. With America and even the world headed into uncertain and possibly turbulent waters, it is important to remember that our voices are worth hearing. We must advocate for ourselves, our values, and our rights, just as past UCSB students have.

Thanks for listening to this episode of Unboxed. Be sure to join us next week when Sophia shares their archive story of unboxing details from the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and be sure to follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.