Intro (1 Min)

[intro music]

“Hey, everyone! Thanks for tuning in! This is the UCSB Undergraduate Journal of History Podcast. This season, we are sharing with you our archive stories of unboxing the stuff of history from the vaults of the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. I’m your host Sophia, a third year history of public policy and law and economics major here at UCSB. In today’s episode of Unboxed, we will dive into the 1970 riots of Isla Vista, including the burning of the Bank of America. The documents from this are brought to us by the Special Research Collections of the UCSB library archives. For some images of today’s archival collection, follow us on Instagram at @ucsbhistjournal. Ok. Let’s see what that grey Hollinger box has in store for us today.

[sound effect]

Act I Duration: (3 Mins)

Our story today comes from the Isla Vista Archives, a collection of 97 boxes of records, audiotapes, cassettes, and more- stored in the University of California’s Special Research Collection. The contents of the boxes describe the history of the local community of Isla Vista, which sits right next to the campus of UCSB. The archive includes records detailing local Isla Vista community issues, relationship with law enforcement, public safety, and more from the 1970s and early 1980s. However, what takes up a large portion of these collections are documents and photographs of the Isla Vista riots of 1970.

Within the collection itself, dozens of arrest records paint a stark picture of the Isla Vista protests of 1970, and the social and political environment that former students experienced. Isla Vista in 1970 felt the impact of growing national pressures. Across the nation, bold social movements for civil rights, women’s rights, and the LGBTQ movement transformed the cultural fabric of American society. Moreover, the Vietnam War and national politics fueled the rise of a growing youth “counterculture” that sought to push back against traditional social norms.

I chose this collection because of my interest in American legal history, particularly the civil rights movement of the late 20th century. As a student at UCSB, I feel it is crucial to understand how this era affected our very own campus and student body, and how they mobilized to respond. Today, more than half a century later, we will dive into the written testimonials of students arrested in the 1970 Isla Vista Riots, in a hope to better understand the local history tied to our University, and why it is important to know today.

Ad

Act II Duration: (3 Mins)

Early opposition to the Vietnam War began in 1965, and included many young quote on quote radicals, and activists that led massive student protests across college campuses. Over time, these peaceful protests sometimes escalated into violent demonstrations. This violence reached Isla Vista on February 25th, 1970, following a scheduled speech by attorney William Kunstler. Hosted by the UCSB Associated Student Government, over 7000 people had gathered to see the lawyer, who had defended the Chicago 8 in their trial for allegedly inciting a police riot during the Democratic National Convention of 1968. After his speech, students began to gather in Perfect Park, located just a walk away from the UCSB campus in Isla Vista. By sundown, hundreds had arrived, and violence began to escalate with local law enforcement.

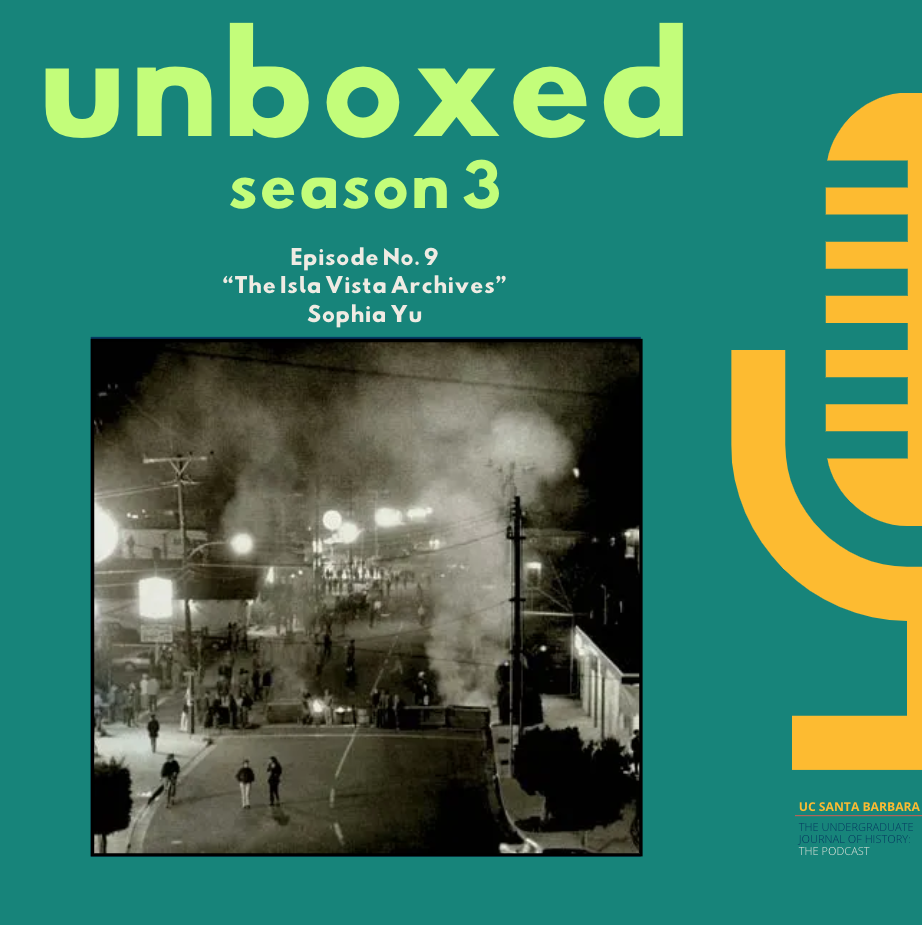

Isla Vista residents were entrenched in the political fervor of the past few days, and on the evening of February 25th 1970, protestors set fire to the inside of the Bank of America building in the center of Isla Vista. Grievances with the Bank included their financial ties to the oppressive South African government apartheid regime, as well as the bank’s connections with US military operations and the exploitation of laborers. For the rest of the evening, chaos ensued on the streets of Isla Vista, with the book Sunshine Revolutionaries describing people throwing objects at nearby cop cars, and residents gathered to watch the building ablaze in the midst of the night.

On February 27th, 1970, local law enforcement enforced a curfew backed by the arrival of national guard troops sent by governor Ronald Reagan. They began sweeping the streets of Isla Vista, a neighborhood less than a square mile large, with police outnumbering residents 3 to 1 in what law enforcement called a “saturation patrol” style. Mass arrests of suspected loiterers occurred as residents got caught between moving guard sweeps. This included Charles R. Ellsworth, a student shopping at the local discount records store around 9:00 pm that night. On his arrest record he describes being “frisked and handcuffed”, “marched to the B.ofA. Parking lot”, “photographed”, and “shoved onto a police bus.” Afterwards, he described “being pulled to the bus by his hair and shoved into a seat” under a “great deal of verbal harassment” by the officers. Ellsworth’s arrest record showcases the handling and treatment of Isla Vista residents in the days following the burning of the bank. Nowhere in his record does he detail any involvement in the destruction of the bank, but he does paint a picture of the chaos and confusion residents of the town were subjected to. Many innocent bystanders were subjected to interactions with the police, and Isla Vista had become emblematic of a mass mobilization of state police power in response to student protests.

[sound effect]

Ad

[sound effect]

Act III Duration: (3 Mins)

The culture of Isla Vista in the late 1960s and early 1970s was certainly not immune to the broader cultural shifts occurring amongst college students. The emergence of 60s counterculture, and “hippie” culture were more than prevalent- as young people sought to reject material culture and embraced nonconformity that challenged social norms. In our arrest records, we see bold and overt opposition to political oppression, and a sharp disdain for law enforcement and institutionalized power.

On March 1, 1970, Student Lane A. Darnton wrote on his arrest record “the idea was to spell OINK in the room lights of Fran. Torres”. He is referencing Francisco Torres, now named Santa Catalina, a two tower residence hall that sits at the intersection of Storke Road and El Colegio Road just off of campus. As Darnton writes, as other students began to gather to see messages spelled out on the lights of their dorm from the lawn outside the building, cops began to arrive and ordered Darnton to halt. He was subsequently arrested and booked for violation of curfew.

Most of those arrested or who came into contact with law enforcement were young, white, male college students. This was the typical demographic that characterized many anti-war protests across US college campuses. Arrest records paint a picture of individuals who fit the popular image of youth counterculture: long hair, Levi’s jeans, corduroy pants, and mustaches. Stephen John Herzog’s record offers a glimpse into the gender dynamics in these encounters. He noted that, when officers entered his friend’s apartment, they “wanted all the guys taken out down to the street. The girls were left in the apartment.” It is possible that in this case, law enforcement targeted the male residents, who represented the more typical demographic of young activists at the time.

The arrest records also highlight a tense moment for the civil and fundamental rights of these young students as they detail their arrests and interactions with law enforcement. On the heels of Miranda V. Arizona court decision in 1966, multiple students noted the failure of law enforcement to inform them of their constitutional rights upon arrest. Charles Ellsworth finished the description of his circumstances of arrest by stating, “Never was I advised of my Constitutional rights, and only after I asked what my charge was did the police tell me what I was arrested for.” Another student in the record store on Friday evening, Kenneth James Deaver, was also arrested and booked for loitering. He wrote on his arrest record “I was not told my rights, I did not run from anyone or resist arrest, I was pushed around by the police but not injured.” Whether or not these students were aware of their specific Constitutional rights is unclear, but their firm recognition of the deprivation of such rights speaks to a larger awareness of social and political rights that had been brewing across the nation.

[sound effect]

Summary (1 Min)

Strolling down the sunny streets of Isla Vista today, it is not difficult to imagine the lives of students in 1970 that walked and protested along the same roads. I still regularly pass by the Santa Catalina dorm towers, where bright messages are spelled out on the windows with sticky notes viewable from the street below. The posters outside of North Hall, where I attend my economics classes, remind us of the establishment of the Black Studies department in 1968 spurred by Black student protestors who demanded institutional change for inclusivity and representation. The former Bank of America is now a lecture hall, embellished with a large bronze plaque commemorating the riots of 1970. The history of UCSB is complex, dynamic, and far from monolithic- something that may not be visible from the idea of palm trees swaying on a beachside campus. However, it is important that we hold onto the legacies and memories of students that fought for social and political change.

[outro music]

Thanks for listening to this episode of Unboxed. Be sure to join us next week when Kate shares their archive story of unboxing the Bud Bottoms Get Oil Out collection from the UCSB Library Special Research Collections. To see some images of today’s archival collection, check out our Instagram page @ucsbhistjournal, and follow us on Spotify at the Undergraduate Journal of History: The Podcast.

[outro music]